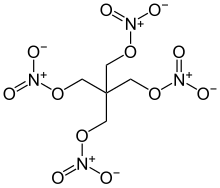

Pentaerythritol tetranitrate

[4][5] Pentaerythritol tetranitrate was first prepared and patented in 1894 by the explosives manufacturer Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprengstoff A.G. [de] of Cologne, Germany.

[12] PETN forms eutectic mixtures with some liquid or molten aromatic nitro compounds, e.g. trinitrotoluene (TNT) or tetryl.

Due to steric hindrance of the adjacent neopentyl-like moiety, PETN is resistant to attack by many chemical reagents; it does not hydrolyze in water at room temperature or in weaker alkaline aqueous solutions.

Gamma radiation increases the thermal decomposition sensitivity of PETN, lowers melting point by few degrees Celsius, and causes swelling of the samples.

[16] Production is by the reaction of pentaerythritol with concentrated nitric acid to form a precipitate which can be recrystallized from acetone to give processable crystals.

[17] Variations of a method first published in US Patent 2,370,437 by Acken and Vyverberg (1945 to Du Pont) form the basis of all current commercial production.

[22][23] PETN is the least stable of the common military explosives, but can be stored without significant deterioration for longer than nitroglycerin or nitrocellulose.

[29] A pulse with duration of 25 nanoseconds and 0.5–4.2 joules of energy from a Q-switched ruby laser can initiate detonation of a PETN surface coated with a 100 nm thick aluminium layer in less than half of a microsecond.

[citation needed] PETN has been replaced in many applications by RDX, which is thermally more stable and has a longer shelf life.

In 1983, the "Maison de France" house in Berlin was brought to a near-total collapse by the detonation of 24 kilograms (53 lb) of PETN by terrorist Johannes Weinrich.

In 1999, Alfred Heinz Reumayr used PETN as the main charge for his fourteen improvised explosive devices that he constructed in a thwarted attempt to damage the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System.

[39] According to US law enforcement officials,[40] he had attempted to blow up Northwest Airlines Flight 253 while approaching Detroit from Amsterdam.

[41] Abdulmutallab had tried, unsuccessfully, to detonate approximately 80 grams (2.8 oz) of PETN sewn into his underwear by adding liquid from a syringe;[42] however, only a small fire resulted.

[21] In the al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula October 2010 cargo plane bomb plot, two PETN-filled printer cartridges were found at East Midlands Airport and in Dubai on flights bound for the US on an intelligence tip.

[44] Hans Michels, professor of safety engineering at University College London, told a newspaper that 6 grams (0.21 oz) of PETN—"around 50 times less than was used—would be enough to blast a hole in a metal plate twice the thickness of an aircraft's skin".

[45] In contrast, according to an experiment conducted by a BBC documentary team designed to simulate Abdulmutallab's Christmas Day bombing, using a Boeing 747 plane, even 80 grams of PETN was not sufficient to materially damage the fuselage.

[43] The Los Angeles Times noted in November 2010 that PETN's low vapor pressure makes it difficult for bomb-sniffing dogs to detect.

[20] Many technologies can be used to detect PETN, including chemical sensors, X-rays, infrared, microwaves[52] and terahertz,[53] some of which have been implemented in public screening applications, primarily for air travel.