Paleontology

Paleontology (/ˌpeɪliɒnˈtɒlədʒi, ˌpæli-, -ən-/ PAY-lee-on-TOL-ə-jee, PAL-ee-, -ən-), also spelled palaeontology[a] or palæontology, is the scientific study of the history of life in the geologic past.

[5] Paleontology lies on the border between biology and geology, but it differs from archaeology in that it excludes the study of anatomically modern humans.

[6] As knowledge has increased, paleontology has developed specialised sub-divisions, some of which focus on different types of fossil organisms while others study ecology and environmental history, such as ancient climates.

The final quarter of the 20th century saw the development of molecular phylogenetics, which investigates how closely organisms are related by measuring the similarity of the DNA in their genomes.

[11] When trying to explain the past, paleontologists and other historical scientists often construct a set of one or more hypotheses about the causes and then look for a "smoking gun", a piece of evidence that strongly accords with one hypothesis over any others.

For example, the 1980 discovery by Luis and Walter Alvarez of iridium, a mainly extraterrestrial metal, in the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary layer made asteroid impact the most favored explanation for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event – although debate continues about the contribution of volcanism.

[10] Paleontology lies between biology and geology since it focuses on the record of past life, but its main source of evidence is fossils in rocks.

[17] In addition, paleontology often borrows techniques from other sciences, including biology, osteology, ecology, chemistry, physics and mathematics.

[19] A relatively recent discipline, molecular phylogenetics, compares the DNA and RNA of modern organisms to re-construct the "family trees" of their evolutionary ancestors.

[20] Techniques from engineering have been used to analyse how the bodies of ancient organisms might have worked, for example the running speed and bite strength of Tyrannosaurus,[21][22] or the flight mechanics of Microraptor.

Palynology, the study of pollen and spores produced by land plants and protists, straddles paleontology and botany, as it deals with both living and fossil organisms.

[32] Paleoclimatology, although sometimes treated as part of paleoecology,[29] focuses more on the history of Earth's climate and the mechanisms that have changed it[33] – which have sometimes included evolutionary developments, for example the rapid expansion of land plants in the Devonian period removed more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing the greenhouse effect and thus helping to cause an ice age in the Carboniferous period.

[37] During the Middle Ages the Persian naturalist Ibn Sina, known as Avicenna in Europe, discussed fossils and proposed a theory of petrifying fluids on which Albert of Saxony elaborated in the 14th century.

[38] In early modern Europe, the systematic study of fossils emerged as an integral part of the changes in natural philosophy that occurred during the Age of Reason.

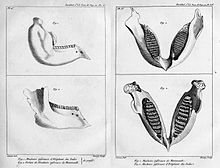

In deeper-level deposits in western Europe are early-aged mammals such as the palaeothere perissodactyl Palaeotherium and the anoplotheriid artiodactyl Anoplotherium, both of which were described earliest after the former two genera, which today are known to date to the Paleogene period.

Interest increased for reasons that were not purely scientific, as geology and paleontology helped industrialists to find and exploit natural resources such as coal.

[37] This contributed to a rapid increase in knowledge about the history of life on Earth and to progress in the definition of the geologic time scale, largely based on fossil evidence.

Although she was rarely recognised by the scientific community,[47] Mary Anning was a significant contributor to the field of palaeontology during this period; she uncovered multiple novel Mesozoic reptile fossils and deducted that what were then known as bezoar stones are in fact fossilised faeces.

[56] In the 1960s molecular phylogenetics, the investigation of evolutionary "family trees" by techniques derived from biochemistry, began to make an impact, particularly when it was proposed that the human lineage had diverged from apes much more recently than was generally thought at the time.

[57] Although this early study compared proteins from apes and humans, most molecular phylogenetics research is now based on comparisons of RNA and DNA.

[59][65] Trace fossils are particularly significant because they represent a data source that is not limited to animals with easily fossilised hard parts, and they reflect organisms' behaviours.

For example, geochemical features of rocks may reveal when life first arose on Earth,[18] and may provide evidence of the presence of eukaryotic cells, the type from which all multicellular organisms are built.

[7] Evolutionary developmental biology, commonly abbreviated to "Evo Devo", also helps paleontologists to produce "family trees", and understand fossils.

[89] While eukaryotes, cells with complex internal structures, may have been present earlier, their evolution speeded up when they acquired the ability to transform oxygen from a poison to a powerful source of metabolic energy.

[96][97] The spread of animals and plants from water to land required organisms to solve several problems, including protection against drying out and supporting themselves against gravity.

[106] Land plants were so successful that their detritus caused an ecological crisis in the Late Devonian, until the evolution of fungi that could digest dead wood.

[34] During the Permian period, synapsids, including the ancestors of mammals, may have dominated land environments,[108] but this ended with the Permian–Triassic extinction event 251 million years ago, which came very close to wiping out all complex life.

[107] During this time mammals' ancestors survived only as small, mainly nocturnal insectivores, which may have accelerated the development of mammalian traits such as endothermy and hair.

[112] After the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago[113] killed off all the dinosaurs except the birds, mammals increased rapidly in size and diversity, and some took to the air and the sea.

[121] There is a long-running debate about whether modern humans are descendants of a single small population in Africa, which then migrated all over the world less than 200,000 years ago and replaced previous hominine species, or arose worldwide at the same time as a result of interbreeding.