Persian art

The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one.

in sources in English) are small cast objects decorated with bronze sculptures from the Early Iron Age which have been found in large numbers in Lorestān Province and Kermanshah in west-central Iran.

[16] The Ziwiye hoard from Kurdistan province of about 700 BC is a collection of objects, mostly in metal, perhaps not all in fact found together, of about the same date, probably showing the art of the Persian cities of the period.

[19] Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a specialty of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of earlier sites.

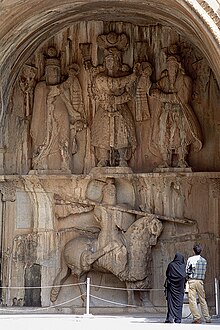

[20] It begins with Lullubi and Elamite rock reliefs, such as those at Sarpol-e Zahab in Iranian Kurdistan (circa 2000 BC), Kul-e Farah and Eshkaft-e Salman in southwest Iran, and continues under the Assyrians.

[21] Persian rulers commonly boasted of their power and achievements, until the Muslim conquest removed imagery from such monuments; much later there was a small revival under the Qajar dynasty.

[22] Behistun is unusual in having a large and important inscription, which like the Egyptian Rosetta Stone repeats its text in three different languages, here all using cuneiform script: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a later form of Akkadian).

The classical archaeologist and director of the excavations, Michael Rostovtzeff, realized that the art of the first centuries AD, Palmyra, Dura Europos, but also in Iran up to the Buddhist India followed the same principles.

[41] The important Sasanian rock reliefs are covered above, and the Parthian tradition of moulded stucco decoration to buildings continued, also including large figurative scenes.

The subjects are similar to other Sasanian art, with enthroned kings, feasts, battles, and beautiful women, and there are illustrations of both Persian and Indian epics, as well as a complex mixture of deities.

In simpler forms it seems to have been available to a wide range of the population, and was a popular luxury export to Byzantium and China, even appearing in elite burials from the period in Japan.

Gold and silver equivalents apparently existed but have been mostly recycled for their precious materials; the few survivals were mostly traded north for furs and then buried as grave goods in Siberia.

Sasanid iconography of mounted heroes, hunting scenes, and seated rulers with attendants remained popular in pottery and metalwork, now often surrounded by elaborate geometrical and calligraphic decoration.

They seized Baghdad in 1048, before dying out in 1194 in Iran, although the production of "Seljuq" works continued through the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th century under the auspices of smaller, independent sovereigns and patrons.

The art of the Persian book was also born under this dynasty, and was encouraged by aristocratic patronage of large manuscripts such as the Jami' al-tawarikh compiled by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, and the Demotte or Great Mongol Shahnameh, probably commissioned by his son.

Though the ethnic make-up gradually blended into the Iranian and Mesopotamian local populations, the Mongol stylism continued well after, and crossed into Asia Minor and even North Africa.

[69] Persian carpets and rugs of various types were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes, in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories alike.

The carpets woven in the Safavid court manufactories of Isfahan during the sixteenth century are famous for their elaborate colours and artistical design, and are treasured in museums and private collections all over the world today.

Their patterns and designs have set an artistic tradition for court manufactories which was kept alive during the entire duration of the Persian Empire up to the last royal dynasty of Iran.

[69] Carpets woven in towns and regional centres like Tabriz, Kerman, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns.

Hand-woven Persian carpets and rugs were regarded as objects of high artistic and utilitarian value and prestige from the first time they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers, until today.

Animals, especially the horses that very often appear, are mostly shown sideways on; even the love-stories that constitute much of the classic material illustrated are conducted largely in the saddle, as far as the prince-protagonist is concerned.

Scholars have noted that extant works from the post-Mongol period contain an abundance of motifs common to Chinese art like dragons, simurgh, cloud-bands, gnarled tree trunks, and lotus and peony flowers.

[84] Tahmasp I was for the early years of his reign a generous funder of the royal workshop, who were responsible for several of the most magnificent Persian manuscripts, but from the 1540s he was increasingly troubled by religious scruples, until in 1556 he finally issued an "Edict of Sincere Repentance" attempting to outlaw miniature painting, music and other arts.

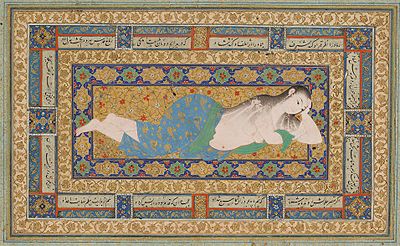

[86] From this dispersal of the royal workshop there was a shift in emphasis from large illustrated books for the court to the production of single sheets designed to be put into a muraqqa, or album.

This new destination led to wider use of Chinese and exotic iconography (elephants) and the introduction of new forms, sometimes astonishing (hookahs, octagonal plates, animal-shaped objects).

Under Shah Ismail, there is a perpetuation of the shapes and decorations of Timurid inlays: motifs of almond-shaped glories, of shamsa (suns) and of chi clouds are found on the inkwells in the form of mausoleums or the globular pitchers reminiscent of Ulugh Beg's jade one.

Hardstone serves also to make jewels to inlay in metal objects, such as the great zinc bottle inlaid with gold, rubies and turquoise dated to the reign of Ismail and conserved at the museum of Topkapi in Istanbul.

The boom in artistic expression that occurred during the Qajar era was the fortunate side effect of the period of relative peace that accompanied the rule of Agha Muhammad Khan and his descendants.

The most famous of these are the myriad portraits which were painted of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, who, with his narrow waist, long black bifurcated beard and deepest eyes, has come to exemplify the Romantic image of the great Oriental Ruler.