Irish phonology

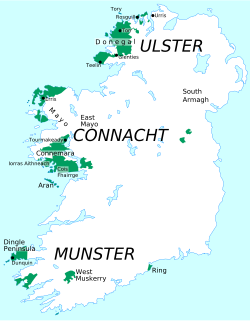

Irish phonology has been studied as a discipline since the late 19th century, with numerous researchers publishing descriptive accounts of dialects from all regions where the language is spoken.

Irish shares a number of phonological characteristics with its nearest linguistic relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, as well as with Hiberno-English, which it currently has the most language contact with.

The first descriptive analysis of the phonology of an Irish dialect was Finck (1899), which was based on the author's fieldwork in the Aran Islands.

More recent descriptive phonology has been published by Lucas (1979) for Rosguill in northern Donegal, Hughes (1986) for Tangaveane and Commeen (also near Glenties), Ó Curnáin (1996) for Iorras Aithneach in Connemara (Kilkieran and vicinity) and Ó Sé (2000) for the Dingle Peninsula, County Kerry.

Most dialects of Irish contain at a minimum the consonant phonemes shown in the following chart (see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols).

/w/ (written as ⟨bh, mh(, v)⟩) has two basic allophones: the labiovelar approximant [w] and the velarized voiced labiodental fricative [vˠ].

[12] In Connacht, [w] is found word-initially before vowels (e.g. bhfuil [wɪlʲ] 'is') and [vˠ] in other positions (e.g. naomh [n̪ˠiːvˠ] 'saint', fómhar [ˈfˠuːvˠəɾˠ] 'autumn', and bhrostaigh [ˈvˠɾˠɔsˠt̪ˠə] 'hurried'[13][14]).

The remaining labial fricatives are typically labiodental [fˠ, fʲ, vʲ], but they as well as the fricative allophone [vˠ] of /w/ have bilabial allophones [ɸˠ, ɸʲ, βˠ, βʲ] in many dialects; the distribution depends partly on environment (bilabials are more likely to be found adjacent to rounded vowels) and partly on the individual speaker.

/tʲ, dʲ/ may be realized as alveolo-palatal affricates [tɕ, dʑ] in a number of dialects, including Tourmakeady,[16] Erris,[17] and Teelin.

[27] In some Ulster varieties, e.g. Tory Island, /x/ can be replaced by [h], e.g. cha [ha] ('not'), be deleted word-finally or before /t̪ˠ/, e.g. santach [ˈsˠan̪ˠt̪ˠa(h)] ('greedy') and seacht [ʃat̪ˠ] ('seven').

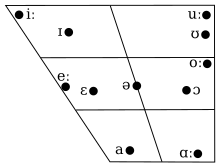

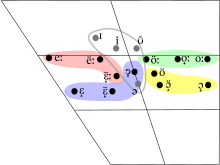

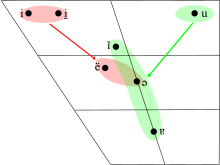

The backness of vowels (that is, the horizontal position of the highest point of the tongue) depends to a great extent on the quality (broad or slender) of adjacent consonants.

The descriptions of the allophones in this section come from Ó Sé (2000:20–24); the pronunciations therefore reflect the Munster accent of the Dingle Peninsula.

Between a slender and a broad consonant, the tongue is retracted slightly from this position (for which the IPA symbol is [i̠ː]), e.g. díol [dʲi̠ːl̪ˠ] ('sale'), caoire [ki̠ːɾʲə] ('berry' gen.).

Between two broad consonants, the tongue is retracted even further, almost to the point of being a central vowel (in IPA, [ïː]): caora [kïːɾˠə] ('sheep').

Unstressed /ə/ is realized as a near-close, near-front [ɪ] when adjacent to a palatal consonant, e.g. píce [ˈpʲiːcɪ] ('pike').

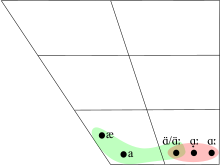

Specifically, long /aː/ in word-initial position and after broad consonants is a back [ɑː], e.g. áit [ɑːtʲ] ('place'), trá [t̪ˠɾˠɑː] ('beach').

In West Muskerry and the Dingle Peninsula, however, the starting point of /əu/ is rounded and further back after broad consonants,[52][53] e.g. gabhar [ɡɔʊɾˠ] ('goat').

Two-consonant clusters consist of an obstruent consonant followed by a liquid or nasal consonant (however, labial obstruents may not be followed by a nasal); examples (from Ní Chiosáin 1999) include bleán /bʲlʲaːnˠ/ ('milking'), breá /bʲɾʲaː/ ('fine'), cnaipe /ˈkn̪ˠapʲə/ ('button'), dlí /dʲlʲiː/ ('law'), gnáth /ɡn̪ˠaː/ ('usual'), pleidhce /ˈpʲlʲəicə/ ('idiot'), slios /ʃlʲɪsˠ/ ('slice'), sneachta /ˈʃnʲaxt̪ˠə/ ('snow'), tlúth /t̪ˠl̪ˠuː/ ('poker'), and tnúth /t̪ˠn̪ˠuː/ ('long for').

In an eclipsis environment, the following are found: mbláth /mˠl̪ˠaː/ ('flower'), mbliana /ˈmʲlʲiən̪ˠə/ ('years'), mbrisfeá /ˈmʲɾʲɪʃaː/ ('you would break'), ndlúth /n̪ˠl̪ˠuː/ ('warp'), ndroichead /ˈn̪ˠɾˠɔhəd̪ˠ/ ('bridge'), ndréimire /ˈnʲɾʲeːmʲəɾʲə/ ('ladder'), ngléasfá /ˈɲlʲeːsˠaː/ ('you would dress'), ngreadfá /ˈɲɾʲat̪ˠaː/ ('you would leave'), ngníomhófá /ˈɲnʲiːwoːhaː/ ('you would act').

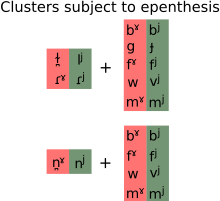

In Donegal, Mayo, and Connemara dialects (but not usually on the Aran Islands), the coronal nasals /nˠ, nʲ/ can follow only /sˠ, ʃ/ respectively in a word-initial cluster.

A cluster of /ɾˠ, ɾʲ/, /l̪ˠ, lʲ/, or /n̪ˠ, nʲ/ followed by a labial or dorsal consonant (except the voiceless stops /pˠ, pʲ/, /k, c/) is broken up by an epenthetic vowel /ə/:[69] borb /ˈbˠɔɾˠəbˠ/ ('abrupt'), gorm /ˈɡɔɾˠəmˠ/ ('blue'), dearmad /ˈdʲaɾˠəmˠəd̪ˠ/ ('mistake'), dearfa /ˈdʲaɾˠəfˠə/ ('certain'), seirbhís /ˈʃɛɾʲəvʲiːʃ/ ('service'), fearg /ˈfʲaɾˠəɡ/ ('anger'), dorcha /ˈd̪ˠɔɾˠəxə/ ('dark'), dalba /ˈd̪ˠal̪ˠəbˠə/ ('bold'), colm /ˈkɔl̪ˠəmˠ/ ('dove'), soilbhir /ˈsˠɪlʲəvʲəɾʲ/ ('pleasant'), gealbhan /ˈɟal̪ˠəwən̪ˠ/ ('sparrow'), binb /ˈbʲɪnʲəbʲ/ ('venom'), Banbha, /ˈbˠan̪ˠəwə/ (a name for Ireland), ainm /ˈanʲəmʲ/ ('name'), meanma /ˈmʲan̪ˠəmˠə/ ('mind'), ainmhí /ˈanʲəvʲiː/ ('animal').

One analysis of these facts[71] is that vowel-initial words actually begin, at an abstract level of representation, with a kind of "empty" consonant that consists of nothing except the information "broad" or "slender".

In Donegal and Mayo, lengthening is found only before ⟨rd, rl, rn⟩, before ⟨rr⟩ (except when a vowel follows), and in a few words also before word-final ⟨ll⟩,[78][79][80][81] e.g. barr /bˠaːɾˠ/ ('top'), ard /aːɾˠd̪ˠ/ ('tall'), orlach /ˈoːɾˠl̪ˠax/ ('inch'), tuirne /ˈt̪uːɾˠn̠ʲə/ ('spinning wheel'), thall /haːl̪ˠ/ ('yonder').

In Connemara,[82] the Aran Islands,[83] and Munster,[84][85] lengthening is found generally not only in the environments listed above, but also before ⟨nn⟩ (unless a vowel follows) and before word-final ⟨m, ng⟩.

[88] Irish exhibits a number of external sandhi effects, i.e. phonological changes across word boundaries, particularly in rapid speech.

In Munster, stress is attracted to a long vowel or diphthong in the second or third syllable of a word, e.g. cailín /kaˈlʲiːnʲ/ ('girl'), achainí /axəˈnʲiː/ ('request').

[98] Also in Munster, an unstressed short vowel is not reduced to /ə/ if the following syllable contains a stressed /iː/ or /uː/, e.g. ealaí /aˈl̪ˠiː/ ('art'), bailiú /bˠaˈlʲuː/ ('gather').

[103] The first eight chapters of Peadar Ua Laoghaire's autobiography Mo Sgéal Féin at Wikisource include recordings of the text being read by a native speaker of Muskerry (Munster) Irish.

[106][107] Manx and many dialects of Scottish Gaelic share with Ulster Irish the property of not reducing unstressed /a/ to /ə/ before /x/.

Hiberno-English also allows /h/ where it is permitted in Irish but excluded in other dialects of English, such as before an unstressed vowel (e.g. Haughey /ˈhɑhi/) and at the end of a word (e.g. McGrath /məˈɡɹæh/).