Greek diacritics

During the Hellenistic period (3rd century BC), Aristophanes of Byzantium introduced the breathings—marks of aspiration (the aspiration however being already noted on certain inscriptions, not by means of diacritics but by regular letters or modified letters)—and the accents, of which the use started to spread, to become standard in the Middle Ages.

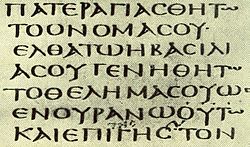

The majuscule, i.e., a system where text is written entirely in capital letters, was used until the 8th century, when the minuscule polytonic supplanted it.

Certain authors have argued that the grave originally denoted the absence of accent; the modern rule is, in their view, a purely orthographic convention.

Others—drawing on, for instance, evidence from ancient Greek music—consider that the grave was "linguistically real" and expressed a word-final modification of the acute pitch.

At the beginning of the 20th century (official since the 1960s), the grave was replaced by the acute, and the iota subscript and the breathings on the rho were abolished, except in printed texts.

The Greek Orthodox church, the daily newspaper Estia, as well as books written in Katharevousa continue to use the polytonic orthography.

Some textbooks of Ancient Greek for foreigners have retained the breathings, but dropped all the accents in order to simplify the task for the learner.

Monotonic orthography for Modern Greek uses only two diacritics, the tonos and diaeresis (sometimes used in combination) that have significance in pronunciation, similar to vowels in Spanish.

The iota subscript was a diacritic invented to mark an etymological vowel that was no longer pronounced, so it was dispensed with as well.

It was also known as ὀξύβαρυς oxýbarys "high-low" or "acute-grave", and its original form (^ ) was from a combining of the acute and grave diacritics.

The smooth breathing (ψιλὸν πνεῦμα, psīlòn pneûma; Latin spīritus lēnis)—'ἀ'—marked the absence of /h/.

In Ancient Greek, the diaeresis (Greek: διαίρεσις or διαλυτικά, dialytiká, 'distinguishing') – ϊ – appears on the letters ι and υ to show that a pair of vowel letters is pronounced separately, rather than as a diphthong or as a digraph for a simple vowel.

[11][12] They are not encoded as precombined characters in Unicode, so they are typed by adding the U+030C ◌̌ COMBINING CARON to the Greek letter.

Latin diacritics on Greek letters may not be supported by many fonts, and as a fall-back a caron may be replaced by an iota ⟨ι⟩ following the consonant.

Diacritics can be found above capital letters in medieval texts and in the French typographical tradition up to the 19th century.

[14] Πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς· ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου· ἐλθέτω ἡ βασιλεία σου· γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου, ὡς ἐν οὐρανῷ, καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς· τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον· καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν, ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφίεμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν· καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν, ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ.

Πάτερ ημών ο εν τοις ουρανοίς· αγιασθήτω το όνομά σου· ελθέτω η βασιλεία σου· γενηθήτω το θέλημά σου, ως εν ουρανώ, και επί της γης· τον άρτον ημών τον επιούσιον δος ημίν σήμερον· και άφες ημίν τα οφειλήματα ημών, ως και ημείς αφίεμεν τοις οφειλέταις ημών· και μη εισενέγκης ημάς εις πειρασμόν, αλλά ρύσαι ημάς από του πονηρού.

Thus: Where a distinction needs to be made (in historic textual analysis, for example), the existence of individual code points and a suitable distinguishing typeface (computer font) make this possible.