Protist locomotion

Unicellular protists comprise a vast, diverse group of organisms that covers virtually all environments and habitats, displaying a menagerie of shapes and forms.

[7] In the process of evolution, single-celled organisms have developed in a variety of directions, and thus their rich morphology results in a large spectrum of swimming modes.

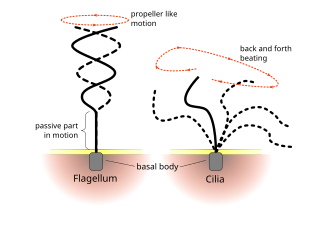

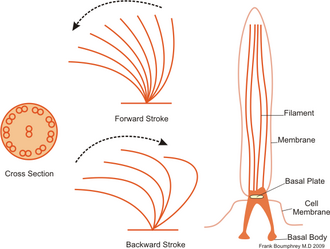

[8][2] Many swimming protists actuate tail-like appendages called flagella or cilia in order to generate the required thrust.

[2] In contrast to flagellates, propulsion of ciliates derives from the motion of a layer of densely-packed and collectively-moving cilia, which are short hair-like flagella covering their bodies.

The seminal review paper of Brennen and Winet (1977) lists a few examples from both groups, highlighting their shape, beat form, geometric characteristics and swimming properties.

From a fluid dynamical perspective,[32] their relatively large size and easy culturing conditions allow for precise studies of their motility, the flows they create with their flagella, and interactions between organisms, while their high degree of symmetry simplifies theoretical descriptions of those same phenomena.

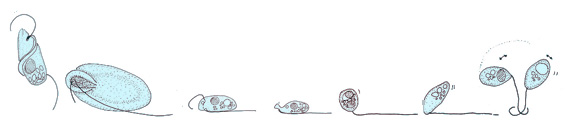

Chlamydomonas swims typically by actuation of its two flagella in a breast stroke, combining propulsion and slow body rotation.

This 8- or 16-cell colony represents one of the first steps to true multicellularity,[49] presumed to have evolved from the unicellular common ancestor earlier than other Volvocine algae.

[26] The 16-cell Gonium colony shown in the diagram on the right is organized into two concentric squares of respectively 4 and 12 cells, each biflagellated, held together by an extracellular matrix.

Yet it performs similar functions to its unicellular and large colonies counterparts as it mixes propulsion and body rotation and swims efficiently toward light.

Early microscopic observations have identified differential flagellar activity between the illuminated and the shaded sides of the colony as the source of phototactic reorientation.

[52][53] Yet a full fluid-dynamics description, quantitatively linking the flagellar response to light variations and the hydrodynamic forces and torques acting on the colony, is still lacking.

[58] Eukaryotes evolved for the first time in the history of life the ability to follow light direction in three dimensions in open water.

A photosensor with a restricted view angle rotates to scan the space and signals periodically to the cilia to alter their beating, which will change the direction of the helical swimming trajectory.

Three-dimensional phototaxis can be found in five out of the six eukaryotic major groups (opisthokonts, Amoebozoa, plants, chromalveolates, excavates, rhizaria).

[57] In the best-studied green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, phototaxis is mediated by a rhodopsin pigment, as first demonstrated by the restoration of normal photobehaviour in a blind mutant by analogues of the retinal chromophore.

Living organisms acclimate to cold and heat stress using acquired mechanisms, including the ability to migrate to an environment with temperatures suitable for inhabitation.

[79] These studies on Paramecium cells highlighted the thermotaxis in unicellular organisms more than 30 years ago, but the molecular mechanisms for thermoreception and signal transduction are not yet understood.

[80][81][82] TRP channels are multimodal sensor for thermal, chemical and mechanical stimuli, but the function of opsins as a thermosensor awaits to be established.

[41][89] The balance depends on the intraflagellar calcium ion concentration; thus, loss of calcium-dependent control in ptx1 mutants results in a phototaxis defect.

[93] In order to initiate fast escape responses, these may have been coupled directly to the motility apparatus—particularly to flexible, membrane-continuous structures such as cilia and pseudopodia.

In protists, all-or-none action potentials occur almost exclusively in association with ciliary membranes,[100][101][102] with the exception of some non-ciliated diatoms.

Depolarizations above a certain threshold result in action potentials, owing to opening of Cav channels located exclusively in the ciliary membrane.

In ciliates, rhythmic depolarizations control fast and slow walking by tentacle-like compound cilia called cirri,[112] enabling escape from dead ends [113] and courtship rituals in conjugating gametes.

[120][121] In 1999, Montemagno and Bachand published an article identifying specific attachment strategies of biological molecules to nanofabricated substrates, enabling the preparation of hybrid inorganic/organic nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS).

[122] They described the production of large amounts of F1-ATPase from the thermophilic bacteria Bacillus PS3 for the preparation of F1-ATPase biomolecular motors immobilized on a nanoarray pattern of gold, copper or nickel produced by electron beam lithography.

Consequently, they accomplished the preparation of a platform with chemically active sites and the development of biohybrid devices capable of converting energy of biomolecular motors into useful work.

[121] Over the past decade, biohybrid microrobots, in which living mobile microorganisms are physically integrated with untethered artificial structures, have gained growing interest to enable the active locomotion and cargo delivery to a target destination.

[123][124][125][126] In addition to the motility, the intrinsic capabilities of sensing and eliciting an appropriate response to artificial and environmental changes make cell-based biohybrid microrobots appealing for transportation of cargo to the inaccessible cavities of the human body for local active delivery of diagnostic and therapeutic agents.

[127][128][129] Active locomotion, targeting and steering of concentrated therapeutic and diagnostic agents embedded in mobile microrobots to the site of action can overcome the existing challenges of conventional therapies.

Cryptaulax , Abollifer , Bodo , Rhynchomonas , Kittoksia , Allas , and Metromonas [ 18 ]

(b) Schematic of a colony of radius a: sixteen cells (green) each with one eye spot (orange dot). The cis flagellum is closest to the eye spot, the trans flagellum is furthest. [ 27 ] Flagella of the central cells beat in an opposing breaststroke, while the peripheral flagella beat in parallel. The pinwheel organization of the peripheral flagella leads to a left-handed body rotation at a rate ω3.

(a) green alga (b) heterokont zoospore (c) cryptomonad alga

(d) dinoflagellate (e) Euglena

Linear distribution of swimming speed data

Bottom: SEM images of bare microalgae (left) and biohybrid microalgae (right) coated with chitosan-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (CSIONPs). Images were pseudocolored. A darker green color on the right SEM image represents chitosan coating on microalgae cell wall. Orange-colored particles represents CSIONPs.