Hyperpolarization (biology)

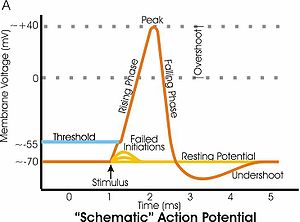

Neurons naturally become hyperpolarized at the end of an action potential, which is often referred to as the relative refractory period.

Relative refractory periods typically last 2 milliseconds, during which a stronger stimulus is needed to trigger another action potential.

Voltage gated potassium, chloride and sodium channels are key components in the generation of the action potential as well as hyper-polarization.

At resting potential, both the voltage gated sodium and potassium channels are closed but as the cell membrane becomes depolarized the voltage gated sodium channels begin to open up and the neuron begins to depolarize, creating a current feedback loop known as the Hodgkin cycle.

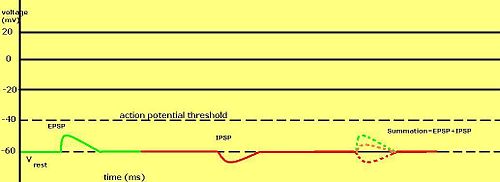

[2] However, potassium ions naturally move out of the cell and if the original depolarization event was not significant enough then the neuron does not generate an action potential.

The neuron continues to re-polarize until the cell reaches ~ –75 mV,[2] which is the equilibrium potential of potassium ions.

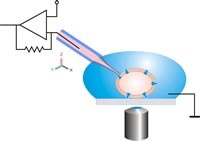

Neuroscientists measure it using a technique known as patch clamping that allows them to record ion currents passing through individual channels.