Proto-Cubism

The term is applied not only to works of this period by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, but to a range of art produced in France during the early 1900s, by such artists as Juan Gris, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, and to variants developed elsewhere in Europe.

[2] Several predominant factors mobilized the shift from a more representational art form to one that would become increasingly abstract; one of the most important would be found directly within the works of Paul Cézanne and exemplified in a widely discussed letter addressed to Émile Bernard dated 15 April 1904.

[2][6] Avant-garde artists in Paris (including Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, André Lhote, Othon Friesz, Georges Braque, Raoul Dufy, Maurice de Vlaminck, Alexander Archipenko and Joseph Csaky) had begun reevaluating their own work in relation to that of Cézanne.

"Paul Fort's Parisian review Vers et Prose", writes Robbins, "as well as the Abbaye de Créteil, cradle of both Jules Romains's Unanimism and Henri-Martin Barzun's Dramatisme, had emphasized the importance of this new formal device".

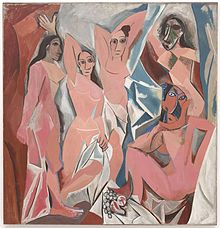

[19][20] Picasso's Rose Period turns toward the theme of the fairground and circus performers; subjects often depicted in Post-Impressionist, romantic and symbolist art and verse (from Baudelaire and Rimbaud to Daumier and Seurat), where melancholy and social alienation pervade the saltimbanque.

At the same time, through Jean Valmy Baysse, an art critic (and soon historian of the Comédie-Française) who was a friend of the Gleizes family, René Arcos is invited to participate on a new journal, La Vie, in collaboration with Alexandre Mercereau, Charles Vildrac and Georges Duhamel.

Gleizes is instrumental in forming the Association Ernest Renan, launched in December at the Théâtre Pigalle, with the aim of countering the influence of militarist propaganda while providing the elements of a popular and secular culture.

I make a kind of chromatic versification and for syllables I use strokes which, variable in quantity, cannot differ in dimension without modifying the rhythm of a pictorial phraseology destined to translate the diverse emotions aroused by nature."

[6][28] "Artists of the years 1910-1914, including Mondrian and Kandinsky as well as the Cubists", writes Robert Herbert, "took support from one of its central principles: that line and color have the ability to communicate certain emotions to the observer, independently of natural form."

The Chahut [Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo] was called by André Salmon "one of the great icons of the new devotion", and both it and the Cirque (Circus), Musée d'Orsay, Paris, according to Guillaume Apollinaire, "almost belong to Synthetic Cubism".

Without doubt, writes Podoksik, Picasso's proto-Cubism—coming as it did not from the external appearance of events and things, but from great emotional and instinctive feelings, from the most profound layers of the psyche—clairvoyantly (as Rimbaud would have said) arrived at the suprapersonal and thereby borders on the archaic mythological consciousness.

"[32][33] European artists (and art collectors) prized these objects for their stylistic traits defined as attributes of primitive expression: absence of classical perspective, simple outlines and shapes, presence of symbolic signs including the hieroglyph, emotive figural distortions, and the dynamic rhythms generated by repetitive ornamental patterns.

In 1905 Eugène Grasset wrote and published Méthode de Composition Ornementale, Éléments Rectilignes[37] within which he systematically explores the decorative (ornamental) aspects of geometric elements, forms, motifs and their variations, in contrast with (and as a departure from) the undulating Art Nouveau style of Hector Guimard and others, so popular in Paris a few years earlier.

These photographic motion studies particularly interested artists that would later form a groups known as the Société Normande de Peinture Moderne and Section d'Or, including Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes and Marcel Duchamp.

[41][42][43] In an interview with Katherine Kuh, Marcel Duchamp spoke about his work and its relation to the photographic motion studies of Muybridge and Marey: "The idea of describing the movement of a nude coming downstairs while still retaining static visual means to do this, particularly interested me.

Popularized too were new scientific discoveries such as Röntgen's X-rays, Hertzian electromagnetic radiation and radio waves propagating through space, revealing realities not only hidden from human observation, but beyond the sphere of sensory perception.

[74][75][76] Disposed to accept the unorthodox in life and art, and naturally tolerant of eccentricity, Gertrude Stein had accommodated the tendency of her Parisian contemporaries of spend their time and talent looking for ways to Épater la bourgeoisie.

[2] Leading up to 1910, one year before the scandalous group exhibiting that brought "Cubism" to the attention of the general public for the first time, the draftsman, illustrator and poet, Gelett Burgess, interviewed and wrote about artists and artworks in and around Paris.

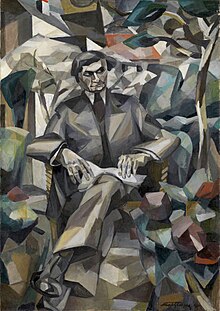

The simplification of representational form gave way to a new complexity; the subject matter of the paintings progressively became dominated by a network of interconnected geometric planes, the distinction between foreground and background no longer sharply delineated, and the depth of field limited.

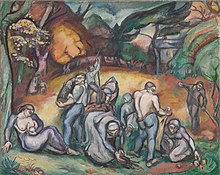

Matisse praises the direct appeal to instinct of the African wood images, and even a sober Dérain, a co-experimenter, loses his head, moulds a neolithic man into a solid cube, creates a woman of spheres, stretches a cat out into a cylinder, and paints it red and yellow!

Chassevent writes: The history of the word "cube" goes back at least to May 1901 when Jean Béral, reviewing Cross's Neo-Impressionist work at the Indépendants in Art et Littérature commented that he "uses a large and square pointillism, giving the impression of mosaic.

"[6][91] During the month of March, 1905, Louis Vauxcelles, in his review of the Salon des Indépendants, published on the front page of Gil Blas, writes: "M. Metzinger, still very young, mimics his elders with the candor of a child throwing handfuls of multicolored confetti; his « point », very big, gives his paintings the appearance of a mosaic".

[98] Louis Vauxcelles, this time in his review of the 26th Salon des Indépendants (1910), made a passing and imprecise reference to Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Léger and Le Fauconnier, as "ignorant geometers, reducing the human body, the site, to pallid cubes.

For Metzinger and Delaunay, too, representational form gave way to a new complexity; the subject matter of the paintings progressively became dominated by a network of interconnected geometric planes, the distinction between foreground and background no longer sharply delineated, and the depth of field limited.

By 1910, the robust form of early analytic Cubism of Picasso (Girl with a Mandolin, Fanny Tellier, 1910), Braque (Violin and Candlestick, 1910) and Metzinger (Nu à la cheminée (Nude), 1910) had become practically indistinguishable.

The term was used derogatorily to describe the diverse geometric concerns reflected in the paintings of five artists in continual communication with one another: Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier and Léger (but not Picasso or Braque, both absent from this massive exhibition).

[91][122] Guillaume Apollinaire, deeming it necessary to deflect the endless attacks throughout the press, accepts the term "Cubism" (the "ism" signifying a tendency of behavior, action or opinion belonging to a class or group of persons (an art movement); the result of an ideology or principle).

[21][117] The term "Cubisme" is employed for the first time outside France in June 1911 by Apollinaire, speaking in the context of an exhibition in Brussels which includes works by Archipenko, Gleizes, Delaunay, Léger, Metzinger, Segonzac, Le Fauconnier, and Jean Marchand.

[91] Apollinaire's impulse was to define L'Esprit nouveau observed in a range of paintings, from proto-Cubist quasi-Fauve landscapes to the semi-abstract geometric compositions of artists such as Metzinger, Delaunay, Gleizes and a growing group of followers.

From which it became clear that these paintings - and I specify the names of the painters who were, alone, the reluctant causes of all this frenzy: Jean Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and myself - appeared as a threat to an order that everyone thought had been established forever.