Quebec French profanity

Sacres are considered stronger in Québec than the foul expressions common to other varieties of French, which centre on sex and excrement (such as merde, "shit").

[2] The sacres originated in the early 19th century, when the social control exerted by the Catholic clergy was increasingly a source of frustration.

[citation needed] The word sacrer in its current meaning is believed to come from the expression Ne dites pas ça, c'est sacré ("Don't say that, it is sacred/holy").

As a result of the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s, the influence of the Roman Catholic Church in Quebec has declined but the profanity still remains in use today.

[2] These sacres are commonly given in a phonetic spelling to indicate the differences in pronunciation from the original word, several of which (notably, the deletion of final consonants and change of [ɛ] to [a] before /ʁ/) are typical of informal Quebec French.

Often, several of these words are strung together when used adjectivally, as in Va t'en, ostie d'câlice de chat à marde!

There is no general agreement on how to write these words, and the Office québécois de la langue française does not regulate them.

[3] The following are also considered milder profanity: Sometimes older people unable to bring themselves to swear with church words or their derivatives would make up ostensibly innocuous phrases, such as cinq six boîtes de tomates vartes (literally, "five or six boxes of green tomatoes", varte being slang for verte, "green").

This phrase when pronounced quickly by a native speaker sounds like saint-siboire de tabarnak ("holy ciborium of the tabernacle").

Depending on the context and the tone of the phrases, it might make everybody quiet, but some people use these words to add rhythm or emphasis to sentences.

For example, in 2003, when punks rioted in Montreal because a concert by the band The Exploited had been cancelled, TV news reporters solemnly read out a few lyrics and song titles from their album Fuck the System.

Since the roughly twenty initial words have generated close to four-hundred euphemisms[6] and thousands of set constructions, all equally present in all regions of Quebec, it would make more sense to have them begin their development at an earlier time than the mid-nineteenth century.

The main Quebec swear words refer to aspects of Catholic worship and practice that Calvinists have historically rejected or objected to, including eucharistic adoration, transubstantiation, the Virgin Mary (viarge) and simony (simonaque).

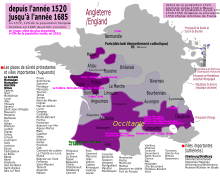

«The reformers unanimously rejected transubstantiation, … understand that words alone are not strong enough to illustrate this philosophy.» and «You have to understand the hatred they feel in the face of what they perceive as a fraud.»[7] About a third of the established settlers came from the Pays de Caux in the Northern part of Normandie «The Pays de Caux... formed a kind of triangle bounded by the port cities of Rouen, Dieppe and Le Havre.

[9] This fact has already been noted in a different context «The geographical areas where women were recruited coincide with the Protestant areas.»[10] It appears that throughout the New-France period, settlement originated from French Protestants strongholds as the increasing pressure from the Counter-Reformation made it harder and harder for them to live in France.

In Italian, although to a lesser extent, some analogous words are in use: in particular, ostia (host) and (more so in the past) sacramento are relatively common expressions in the northeast, which are lighter (and a little less common) than the typical blasphemies in use in Italy, such as porco Dio (pig god) and porca Madonna (see Italian profanity).

Other dialects in the world feature this kind of profanity, such as the expressions Sakrament and Kruzifix noch einmal in Austro-Bavarian and krucifix in Czech.

Spanish also uses me cago en ... ("I shit on ...") followed by "God", "the blessed chalice", "the Virgin" and other terms, religious or not.

is sometimes used with "Easter", "Christ", "Cross", "Commemoration" (parastas), "sacred oil lamp" (tu-i candela 'mă-sii), "God", "Church", etc.

Irish Catholics of old employed a similar practice, whereby "ejaculations" were used to express frustration without cursing or profaning (taking the Lord's name in vain).