Rangaku

Rangaku (Kyūjitai: 蘭學,[a] English: Dutch learning), and by extension Yōgaku (Japanese: 洋学, "Western learning"), is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Western technology and medicine in the period when the country was closed to foreigners from 1641 to 1853 because of the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of national isolation (sakoku).

Through Rangaku, some people in Japan learned many aspects of the scientific and technological revolution occurring in Europe at that time, helping the country build up the beginnings of a theoretical and technological scientific base, which helps to explain Japan's success in its radical and speedy modernization following the forced American opening of the country to foreign trade in 1854.

They became instrumental, however, in transmitting to Japan some knowledge of the Industrial and Scientific Revolution that was occurring in Europe: In 1720 the ban on Dutch books was lifted and the Japanese purchased and translated scientific books from the Dutch, obtained from them Western curiosities and manufactures (such as clocks, medical instruments, celestial and terrestrial globes, maps and plant seeds) and received demonstrations of Western innovations, including of electrical phenomena, as well as the flight of a hot air balloon in the early 19th century.

While other European countries faced ideological and political battles associated with the Protestant Reformation, the Netherlands were a free state, attracting leading thinkers such as René Descartes.

Initially, a small group of hereditary Japanese–Dutch translators labored in Nagasaki to smooth communication with the foreigners and transmit bits of Western novelties.

One of the most important surgeons was Caspar Schamberger, who induced a continuing interest in medical books, instruments, pharmaceuticals, treatment methods etc.

During the second half of the 17th century high-ranking officials ordered telescopes, clocks, oil paintings, microscopes, spectacles, maps, globes, birds, dogs, donkeys, and other rarities for their personal entertainment and for scientific studies.

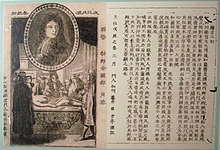

The book details a vast array of topics: it includes objects such as microscopes and hot air balloons; discusses Western hospitals and the state of knowledge of illness and disease; outlines techniques for painting and printing with copper plates; it describes the makeup of static electricity generators and large ships; and it relates updated geographical knowledge.

The German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold, attached to the Dutch delegation, established exchanges with Japanese students.

In 1839, scholars of Western studies (called 蘭学者 "rangaku-sha") briefly suffered repression by the Edo shogunate in the Bansha no goku (蛮社の獄, roughly "imprisonment of the society for barbarian studies") incident, due to their opposition to the introduction of the death penalty against foreigners (other than Dutch) coming ashore, recently enacted by the Bakufu.

Students were sent abroad, and foreign employees (o-yatoi gaikokujin) came to Japan to teach and advise in large numbers, leading to an unprecedented and rapid modernization of the country.

Great debates occurred between the proponents of traditional Chinese medicine and those of the new Western learning, leading to waves of experiments and dissections.

The latter was a compilation made by several Japanese scholars, led by Sugita Genpaku, mostly based on the Dutch-language Ontleedkundige Tafelen of 1734, itself a translation of Anatomische Tabellen (1732) by the German author Johann Adam Kulmus.

Shizuki coined several key scientific terms for the translation, which are still in use in modern Japanese; for example, "gravity" (重力, jūryoku), "attraction" (引力, inryoku) (as in electromagnetism), and "centrifugal force" (遠心力, enshinryoku).

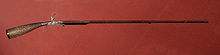

[4] In 1831, after having spent several months in Edo where he could get accustomed with Dutch wares, Kunitomo Ikkansai (a former gun manufacturer) built Japan's first reflecting telescope of the Gregorian type.

[citation needed] Magic lanterns, first described in the West by Athanasius Kircher in 1671, became very popular attractions in multiple forms in 18th-century Japan.

The mechanism of a magic lantern, called "shadow picture glasses" (影絵眼鏡, Kagee Gankyō) was described using technical drawings in the book titled Tengu-tsū (天狗通) in 1779.

Japan adapted and transformed the Western automata, which were fascinating the likes of Descartes, giving him the incentive for his mechanist theories of organisms, and Frederick the Great, who loved playing with automatons and miniature wargames.

In 1805, almost twenty years later, the Swiss Johann Caspar Horner and the Prussian Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, two scientists of the Kruzenshtern mission that also brought the Russian ambassador Nikolai Rezanov to Japan, made a hot air balloon out of Japanese paper (washi) and made a demonstration of the new technology in front of about 30 Japanese delegates.

[6] Hot air balloons would mainly remain curiosities, becoming the object of experiments and popular depictions, until the development of military usages during the early Meiji period.

[citation needed] Modern geographical knowledge of the world was transmitted to Japan during the 17th century through Chinese prints of Matteo Ricci's maps as well as globes brought to Edo by chiefs of the VOC trading post Dejima.

This knowledge was regularly updated through information received from the Dutch, so that Japan had an understanding of the geographical world roughly equivalent to that of contemporary Western countries.

The description of the natural world made considerable progress through Rangaku; this was influenced by the Encyclopedists and promoted by von Siebold (a German doctor in the service of the Dutch at Dejima).

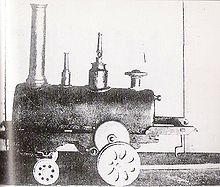

[citation needed] When Commodore Perry obtained the signature of treaties at the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854, he brought technological gifts to the Japanese representatives.

In 1858, the Dutch officer Kattendijke commented: There are some imperfections in the details, but I take my hat off to the genius of the people who were able to build these without seeing an actual machine, but only relied on simple drawings.

Scholars such as Fukuzawa Yukichi, Ōtori Keisuke, Yoshida Shōin, Katsu Kaishū, and Sakamoto Ryōma built on the knowledge acquired during Japan's isolation and then progressively shifted the main language of learning from Dutch to English.

As these Rangaku scholars usually took a pro-Western stance, which was in line with the policy of the Shogunate (Bakufu) but against anti-foreign imperialistic movements, several were assassinated, such as Sakuma Shōzan in 1864 and Sakamoto Ryōma in 1867.