Religiosity

[3] Different scholars have seen this concept as broadly about religious orientations and degrees of involvement or commitment.

[7] The measurement of religiosity is hampered by the difficulties involved in defining what is meant by the term and what components it includes.

For instance, Marie Cornwall and colleagues identify six dimensions of religiosity based on the understanding that there are at least three components to religious behavior: knowing (cognition in the mind), feeling (effect to the spirit), and doing (behavior of the body).

[19] Decades of anthropological, sociological, and psychological research have established that the common assumption of "religious congruence" is rarely accurate.

The beliefs, affiliations, and behaviors of any individual are complex activities that have many sources including culture.

Mark Chaves gives the following examples of religious incongruence: "Observant Jews may not believe what they say in their Sabbath prayers.

"[6] Decades of anthropological, sociological, and psychological research have shown that congruence between an individual's beliefs, attitudes, and behavior concerning religion and irreligion is rare.

[20] The reliability of any poll results, in general and specifically on religion, can be questioned due numerous factors such as:[21] Researchers also note that an estimated 20–40% of the population changes their self-reported religious affiliation/identity over time due to numerous factors and that usually it is their answers on surveys that change, not necessarily their religious practices or beliefs.

[24] Two major surveys in the United States, the General Social Survey (GSS) and the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), have consistently produced discrepancies between their demographic estimates on religion that amount to 8% and growing.

The conductors of the study concluded, "The historic reluctance of Americans to self-identify in this manner or use these terms seems to have diminished.

[27] Gallup's editor-in-chief, Frank Newport, argues that numbers on surveys may give an incomplete picture.

In his view, declines in religious affiliation or belief in God on surveys may not actually reflect real declines, but instead increased honesty to interviewers on spiritual matters due to viewpoints previously seen as deviant becoming more socially acceptable.

"[29] Due to the complexity of measuring religious identity, censuses sometimes also overestimate groups; this was the case for Christians in Britain, as typically one person fills out the census one behalf of a household, as distinguished from surveys which ask individual adults.

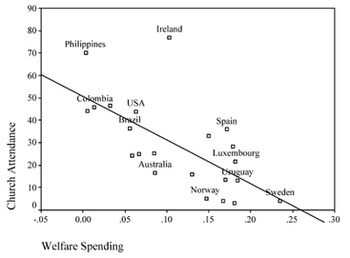

However, researchers Anthony Gill and Eric Lundsgaarde documented a much stronger correlation between welfare state spending and religiosity (see diagram).