Renaissance magic

In medieval stories, magic had a fantastical and fairy-like quality, while in the Renaissance, it became more complex and tied to the idea of hidden knowledge that could be explored through books and rituals.

[1] Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, a scholar, physician, and astrologer, popularized the Hermetic and Cabalistic magic of Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

Johann Weyer, a Dutch physician and disciple of Agrippa, advocated against the persecution of witches and argued that accusations of witchcraft were often based on mental disturbances.

Intellectual and spiritual tensions erupted in the Early Modern witch craze, further reinforced by the turmoils of the Protestant Reformation, especially in Germany, England, and Scotland.

[5] As revealed in his last literary work, the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he only circulated among close friends, he rejected Christianity in favour of a return to the worship of the classical Hellenic Gods, mixed with ancient wisdom based on Zoroaster and the Magi.

His medical works exerted considerable influence on Renaissance physicians such as Paracelsus, with whom he shared the perception on the unity of the micro- and macrocosmos, and their interactions, through somatic and psychological manifestations, with the aim to investigate their signatures to cure diseases.

[18] Similarly, Pico believed that an educated person should also study Hebrew and Talmudic sources, and the Hermetics, because he thought they represented the same concept of God that is seen in the Old Testament, but in different words.

Following Pico, Reuchlin seemed to find in the Kabbala a profound theosophy which might be of the greatest service for the defence of Christianity and the reconciliation of science with the mysteries of faith, a common notion at that time.

Later records give a more positive verdict; thus the Tübingen professor Joachim Camerarius in 1536 recognises Faust as a respectable astrologer, and physician Philipp Begardi of Worms in 1539 praises his medical knowledge.

[a] Other writers on occult or magical topics during this period include: C. S. Lewis in his 1954 English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama differentiates what he takes to be the change of character in magic as practiced in the Middle Ages as opposed to the Renaissance: Only an obstinate prejudice about this period could blind us to a certain change which comes over the merely literary texts as we pass from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century.

[25] The Cabalistic and Hermetic magic, which was created by Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), was made popular in northern Europe, most notably England, by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535), via his De occulta philosophia libra tres (1531–1533).

Considerable space is devoted to examples of evil sorcery in De occulta philosophia, and one might easily come away from the treatise with the impression that Agrippa found witchcraft as intriguing as benevolent magic.

[27] However, at the peak of the witch trials, there was a certain danger to be associated with witchcraft or sorcery, and most learned authors took pains to clearly renounce the practice of forbidden arts.

[29][30] As a physician of the early 16th century, Paracelsus held a natural affinity with the Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Pythagorean philosophies central to the Renaissance, a world-view exemplified by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.

It was mainly in response to the almanacs that the nobility and other prominent persons from far away soon started asking for horoscopes and psychic advice from him, though he generally expected his clients to supply the birth charts on which these would be based, rather than calculating them himself as a professional astrologer would have done.

When obliged to attempt this himself on the basis of the published tables of the day, he frequently made errors and failed to adjust the figures for his clients' place or time of birth.

[37][38][39] He then began his project of writing his book Les Prophéties, a collection of 942 poetic quatrains[d] which constitute the largely undated prophecies for which he is most famous today.

Feeling vulnerable to opposition on religious grounds,[41] however, he devised a method of obscuring his meaning by using "Virgilianised" syntax, word games and a mixture of other languages such as Greek, Italian, Latin, and Provençal.

In the years since the publication of his Les Prophéties, Nostradamus has attracted many supporters, who, along with much of the popular press, credit him with having accurately predicted many major world events.

[46] These academics also argue that Nostradamus's predictions are characteristically vague, meaning they could be applied to virtually anything, and are useless for determining whether their author had any real prophetic powers.

Weyer criticised the Malleus Maleficarum and the witch hunting by the Christian and Civil authorities; he is said to have been the first person that used the term mentally ill or melancholy to designate those women accused of practicing witchcraft.

While he defended the idea that the Devil's power was not as strong as claimed by the orthodox Christian churches in De Praestigiis Daemonum, he also defended the idea that demons did have power and could appear before people who called upon them, creating illusions; but he commonly referred to magicians and not to witches when speaking about people who could create illusions, saying they were heretics who were using the Devil's power to do it, and when speaking on witches, he used the term mentally ill.[48] Moreover, Weyer did not only write the catalogue of demons Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, but also gave their description and the conjurations to invoke them in the appropriate hour and in the name of God and the Trinity, not to create illusions but to oblige them to do the conjurer's will, as well as advice on how to avoid certain perils and tricks if the demon was reluctant to do what he was commanded or a liar.

Weyer's appeal for clemency for those accused of the crime of witchcraft was opposed later in the sixteenth century by the Swiss physician Thomas Erastus, the French legal theorist Jean Bodin and King James VI of Scotland.

[53] His goal was to help bring forth a unified world religion through the healing of the breach of the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches and the recapture of the pure theology of the ancients.

[52] In 1564, Dee wrote the Hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica ("The Hieroglyphic Monad"), an exhaustive Cabalistic interpretation of a glyph of his own design, meant to express the mystical unity of all creation.

Having dedicated it to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor in an effort to gain patronage, Dee attempted to present it to him at the time of his ascension to the throne of Hungary.

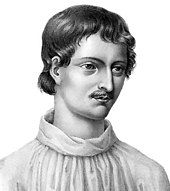

Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Islamic astrology (particularly the philosophy of Averroes),[65] Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and Genesis-like legends surrounding the Egyptian god Thoth.

Starting in 1593, Bruno was tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition on charges of denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, and transubstantiation.

Khunrath's brushes with John Dee and Thölde and Paracelsian beliefs led him to develop a Christianized natural magic, seeking to find the secret prima materia that would lead man into eternal wisdom.

John Warwick Montgomery has pointed out that Johann Arndt (1555–1621), who was the influential writer of Lutheran books of pietiesm and devotion, composed a commentary on Amphitheatrum.