Rhumb line

Navigation on a fixed course (i.e., steering the vessel to follow a constant cardinal direction) would result in a rhumb-line track.

The effect of following a rhumb line course on the surface of a globe was first discussed by the Portuguese mathematician Pedro Nunes in 1537, in his Treatise in Defense of the Marine Chart, with further mathematical development by Thomas Harriot in the 1590s.

A rhumb line can be contrasted with a great circle, which is the path of shortest distance between two points on the surface of a sphere.

Meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude provide special cases of the rhumb line, where their angles of intersection are respectively 0° and 90°.

As Leo Bagrow states:[4] the word ('Rhumbline') is wrongly applied to the sea-charts of this period, since a loxodrome gives an accurate course only when the chart is drawn on a suitable projection.

Cartometric investigation has revealed that no projection was used in the early charts, for which we therefore retain the name 'portolan'.For a sphere of radius 1, the azimuthal angle λ, the polar angle −π/2 ≤ φ ≤ π/2 (defined here to correspond to latitude), and Cartesian unit vectors i, j, and k can be used to write the radius vector r as Orthogonal unit vectors in the azimuthal and polar directions of the sphere can be written which have the scalar products λ̂ for constant φ traces out a parallel of latitude, while φ̂ for constant λ traces out a meridian of longitude, and together they generate a plane tangent to the sphere.

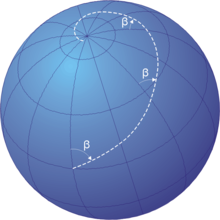

With this relationship between λ and φ, the radius vector becomes a parametric function of one variable, tracing out the loxodrome on the sphere: where is the isometric latitude.

Then, if we define the map coordinates of the Mercator projection as a loxodrome with constant bearing β from true north will be a straight line, since (using the expression in the previous section) with a slope Finding the loxodromes between two given points can be done graphically on a Mercator map, or by solving a nonlinear system of two equations in the two unknowns m = cot β and λ0.

There are infinitely many solutions; the shortest one is that which covers the actual longitude difference, i.e. does not make extra revolutions, and does not go "the wrong way around".

Over the Earth's surface at low latitudes or over short distances it can be used for plotting the course of a vehicle, aircraft or ship.

[1] Over longer distances and/or at higher latitudes the great circle route is significantly shorter than the rhumb line between the same two points.

However the inconvenience of having to continuously change bearings while travelling a great circle route makes rhumb line navigation appealing in certain instances.

[1] The point can be illustrated with an east–west passage over 90 degrees of longitude along the equator, for which the great circle and rhumb line distances are the same, at 10,000 kilometres (5,400 nautical miles).

A more extreme case is the air route between New York City and Hong Kong, for which the rhumb line path is 18,000 km (9,700 nmi).

The great circle route over the North Pole is 13,000 km (7,000 nmi), or 5+1⁄2 hours less flying time at a typical cruising speed.

Note: this article incorporates text from the 1878 edition of The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information, a work in the public domain