Poincaré conjecture

In the mathematical field of geometric topology, the Poincaré conjecture (UK: /ˈpwæ̃kæreɪ/,[2] US: /ˌpwæ̃kɑːˈreɪ/,[3][4] French: [pwɛ̃kaʁe]) is a theorem about the characterization of the 3-sphere, which is the hypersphere that bounds the unit ball in four-dimensional space.

The eventual proof built upon Richard S. Hamilton's program of using the Ricci flow to solve the problem.

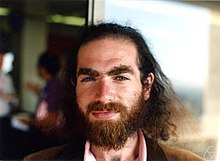

By developing a number of new techniques and results in the theory of Ricci flow, Grigori Perelman was able to modify and complete Hamilton's program.

This analogue is known to be true via the classification of closed and connected two-dimensional topological manifolds, which was understood in various forms since the 1860s.

In higher dimensions, the closed and connected topological manifolds do not have a straightforward classification, precluding an easy resolution of the Poincaré conjecture.

Riemann had showed that a closed connected two-dimensional manifold is fully characterized by its Betti numbers.

As part of his 1895 paper Analysis Situs (announced in 1892), Poincaré showed that Riemann's result does not extend to higher dimensions.

He posed the question of whether the fundamental group is sufficient to topologically characterize a manifold (of given dimension), although he made no attempt to pursue the answer, saying only that it would "demand lengthy and difficult study".

Following criticism of the completeness of his arguments, he released a number of subsequent "supplements" to enhance and correct his work.

The closing remark of his second supplement, published in 1900, said:[15][13] In order to avoid making this work too prolonged, I confine myself to stating the following theorem, the proof of which will require further developments: Each polyhedron which has all its Betti numbers equal to 1 and all its tables Tq orientable is simply connected, i.e., homeomorphic to a hypersphere.

[14] Throughout the work of Riemann, Betti, and Poincaré, the topological notions in question are not defined or used in a way that would be recognized as precise from a modern perspective.

Influential mathematicians such as Georges de Rham, R. H. Bing, Wolfgang Haken, Edwin E. Moise, and Christos Papakyriakopoulos attempted to prove the conjecture.

In 1958, R. H. Bing proved a weak version of the Poincaré conjecture: if every simple closed curve of a compact 3-manifold is contained in a 3-ball, then the manifold is homeomorphic to the 3-sphere.

[24][25] An exposition of attempts to prove this conjecture can be found in the non-technical book Poincaré's Prize by George Szpiro.

A stronger assumption than simply-connectedness is necessary; in dimensions four and higher there are simply-connected, closed manifolds which are not homotopy equivalent to an n-sphere.

While the complete work is an accumulated efforts of many geometric analysts, the major contributors are unquestionably Hamilton and Perelman.All three groups found that the gaps in Perelman's papers were minor and could be filled in using his own techniques.

[40] In December 2006, the journal Science honored the proof of Poincaré conjecture as the Breakthrough of the Year and featured it on its cover.

[5] Hamilton's program for proving the Poincaré conjecture involves first putting a Riemannian metric on the unknown simply connected closed 3-manifold.

So, in effect, Hamilton showed a special case of the Poincaré conjecture: if a compact simply-connected 3-manifold supports a Riemannian metric of positive Ricci curvature, then it must be diffeomorphic to the 3-sphere.

Perelman's major achievement was to show that, if one takes a certain perspective, if they appear in finite time, these singularities can only look like shrinking spheres or cylinders.

On November 11, 2002, Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman posted the first of a series of three eprints on arXiv outlining a solution of the Poincaré conjecture.

In August 2006, Perelman was awarded, but declined, the Fields Medal (worth $15,000 CAD) for his work on the Ricci flow.

On March 18, 2010, the Clay Mathematics Institute awarded Perelman the $1 million Millennium Prize in recognition of his proof.

Perelman and Hamilton then chop the manifold at the singularities (a process called "surgery"), causing the separate pieces to form into ball-like shapes.

Perelman proved this using something called the "Reduced Volume", which is closely related to an eigenvalue of a certain elliptic equation.

Eigenvalues are closely related to vibration frequencies and are used in analyzing a famous problem: can you hear the shape of a drum?

This helped him eliminate some of the more troublesome singularities that had concerned Hamilton, particularly the cigar soliton solution, which looked like a strand sticking out of a manifold with nothing on the other side.

Completing the proof, Perelman takes any compact, simply connected, three-dimensional manifold without boundary and starts to run the Ricci flow.

He cuts the strands and continues deforming the manifold until, eventually, he is left with a collection of round three-dimensional spheres.

A minimal surface is one on which any local deformation increases area; a familiar example is a soap film spanning a bent loop of wire.