Richard I of Normandy

[1] Dudo of Saint-Quentin, whom Richard commissioned to write the "De moribus et actis primorum Normanniae ducum" (Latin, "On the Customs and Deeds of the First Dukes of Normandy"), called him a dux.

[11] Upon hearing that Richard was being held in captivity, the boy's foster Osmond de Centville and Bernard the Dane formed a mob of knights and peasants across town and marched to the King's palace.

[14][15] In 946, at the age of 14, Richard allied himself with the Norman and Viking leaders in France and with men sent by Harold of Denmark.

[9]: 41–2 Louis, working with Arnulf, persuaded Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor to attack Richard and Hugh.

The combined armies of Otto, Arnulf, and Louis were driven from the gates of Rouen, fleeing to Amiens and being decisively defeated in 947.

For the last 30 years of his reign, Richard concentrated on Normandy itself, and participated less in Frankish politics and its petty wars.

[22] However, in 2016, what was believed to be his tomb was opened by Norwegian researchers who discovered that the interred remains could not have been those of Richard, as testing revealed that they were much older.

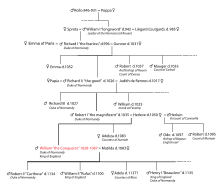

[25] His daughters forged valuable marriage alliances with powerful neighboring counts as well as to the king of England.

Richard also built on his relationship with the church, undertaking acts of piety,[26]: lv restoring their lands and ensuring the great monasteries flourished in Normandy.

[1] According to Robert of Torigni, not long after Emma's death, Duke Richard went out hunting and stopped at the house of a local forester.

He became enamored with the forester's wife, Seinfreda, but she was a virtuous woman and suggested he court her unmarried sister, Gunnor, instead.