Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

The classical rocket equation, or ideal rocket equation is a mathematical equation that describes the motion of vehicles that follow the basic principle of a rocket: a device that can apply acceleration to itself using thrust by expelling part of its mass with high velocity and can thereby move due to the conservation of momentum.

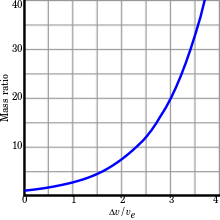

where: Given the effective exhaust velocity determined by the rocket motor's design, the desired delta-v (e.g., orbital speed or escape velocity), and a given dry mass

The equation is named after Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who independently derived it and published it in his 1903 work.

[5][2] The equation had been derived earlier by the British mathematician William Moore in 1810,[3] and later published in a separate book in 1813.

[4] American Robert Goddard independently developed the equation in 1912 when he began his research to improve rocket engines for possible space flight.

German engineer Hermann Oberth independently derived the equation about 1920 as he studied the feasibility of space travel.

While the derivation of the rocket equation is a straightforward calculus exercise, Tsiolkovsky is honored as being the first to apply it to the question of whether rockets could achieve speeds necessary for space travel.

In order to understand the principle of rocket propulsion, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky proposed the famous experiment of "the boat".

Effectively, the quantity of movement of the stones thrown in one direction corresponds to an equal quantity of movement for the boat in the other direction (ignoring friction / drag).

) to the change in linear momentum of the whole system (including rocket and exhaust) as follows:

In free space, for the case of acceleration in the direction of the velocity, this is the increase of the speed.

In the case of an acceleration in opposite direction (deceleration) it is the decrease of the speed.

The equation can also be derived from the basic integral of acceleration in the form of force (thrust) over mass.

is the initial mass minus the final (dry) mass, and realising that the integral of a resultant force over time is total impulse, assuming thrust is the only force involved,

Imagine a rocket at rest in space with no forces exerted on it (Newton's First Law of Motion).

From the moment its engine is started (clock set to 0) the rocket expels gas mass at a constant mass flow rate R (kg/s) and at exhaust velocity relative to the rocket ve (m/s).

This creates a constant force F propelling the rocket that is equal to R × ve.

The rocket is subject to a constant force, but its total mass is decreasing steadily because it is expelling gas.

According to Newton's Second Law of Motion, its acceleration at any time t is its propelling force F divided by its current mass m:

Now, the mass of fuel the rocket initially has on board is equal to m0 – mf.

For the constant mass flow rate R it will therefore take a time T = (m0 – mf)/R to burn all this fuel.

Integrating both sides of the equation with respect to time from 0 to T (and noting that R = dm/dt allows a substitution on the right) obtains:

If special relativity is taken into account, the following equation can be derived for a relativistic rocket,[7] with

Delta-v (literally "change in velocity"), symbolised as Δv and pronounced delta-vee, as used in spacecraft flight dynamics, is a measure of the impulse that is needed to perform a maneuver such as launching from, or landing on a planet or moon, or an in-space orbital maneuver.

Delta-v is produced by reaction engines, such as rocket engines, is proportional to the thrust per unit mass and burn time, and is used to determine the mass of propellant required for the given manoeuvre through the rocket equation.

It also holds true for rocket-like reaction vehicles whenever the effective exhaust velocity is constant, and can be summed or integrated when the effective exhaust velocity varies.

In what has been called "the tyranny of the rocket equation", there is a limit to the amount of payload that the rocket can carry, as higher amounts of propellant increment the overall weight, and thus also increase the fuel consumption.

[8] The equation does not apply to non-rocket systems such as aerobraking, gun launches, space elevators, launch loops, tether propulsion or light sails.

This assumption is relatively accurate for short-duration burns such as for mid-course corrections and orbital insertion maneuvers.

For low-thrust, long duration propulsion, such as electric propulsion, more complicated analysis based on the propagation of the spacecraft's state vector and the integration of thrust are used to predict orbital motion.