Roman army of the late Republic

After the Social War, and following the establishment of the First Triumvirate by Julius Caesar, Licinius Crassus, and Pompeius Magnus, there grew an emphasis on the expansion of a united Republic toward regions such as Britain and Parthia.

The effort to quell the invasions and revolts of non-Romans persisted throughout the period, from Marius’ battles with the wandering Germans in Italy to Caesar's campaign in Gaul.

[3] The non-Italian allies that had long fought for Rome (e.g., Gallic and Numidian cavalry) continued to serve alongside the legions but remained irregular units under their own leaders.

Ambitious commanders, driven by a desire to distinguish themselves from their contemporaries, led massive campaigns to expand the empire's borders far beyond the region of Italy.

[6] The frequency of war, the prolonged duration of the campaigns, and the growing demand for garrisons resulted in the legions to develop a much more permanent and professional character.

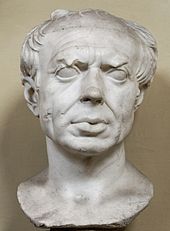

[8] After receiving permission from the Plebeian Council to command the army in 107 BC, Gaius Marius marched through Numidia to take the town of Capsa whose entire population was either killed or sold into slavery.

Marius showcased his army's capability once again, first massacring 90,000 of the 100,000 Teutones soldiers, which included women and children, implementing a well-coordinated rear ambush tactic.

The Social War opened in 91 BC when Italians began to revolt because the Senate would not grant them Roman citizenship even though they showed loyalty in fighting for Rome in the past.

At the completion of the Social War in 89 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix marched on Rome with six legions, who devoted their loyalty solely to him, as a means of coercing the Plebeian Council to grant him authority to fight King Mithridates of Pontus who invaded the Roman province of Asia.

In 83 BC, following his capture of Athens from Mithridates, Sulla returned to Rome, joined his army of 35,000 veterans with three legions raised by the young Pompey to defeat a lone consul's 100,000 newly recruited.

He defeated the larger Pompeian armies through the experience of his men and clever use of strategy, even employing the pilum as a bayonet to combat Pompey's 7–1 cavalry advantage.

Caesar's assassination led to the creation of the Second Triumvirate of Octavian (to become known as Augustus), Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in 43 BC.

Exemplifying the mobility of loyalty in the army of this period, Octavian was able to raise legions without legal command as a result of his Caesarian connection, two of which had defected from Antony.

Even though the Roman military power concentrated on heavy infantry, the importance of naval warfare was displayed in the final Battle of Actium, where Octavian achieved total victory.

[9] The standard legion contained thirty maniples organized into three distinct lines, and consisted of about 4,200 infantrymen and 300 Roman citizen cavalrymen (equites).

Other changes were supposed to have included the introduction of the cohort; the institution of a single form of heavy infantry with uniform equipment; the universal adoption of the eagle standard; and the abolition of the citizen cavalry.

[13] It was commonly believed that Marius changed the soldiers' socio-economic background by allowing citizens without property to join the Roman army, a process called "proletarianisation".

[28] Following the conclusion of the Social War, soldiers in the Roman army began to acquire a specialized expertise alongside their regular legionary duty.

[35] Their elimination has traditionally been linked to Marius, to whom several other changes in organization and equipment have also been ascribed; however, no concrete proof of such a reform has ever been found.

The Social War strained the Roman manpower resources as its allies and clients, who had supplied soldiers to Rome in the past, revolted against them.

[39] With the granting of citizenship to all Italian communities and the growing significance of wealth and income to status, cavalry service, which had been used to climb the ranks of society in the past, may have decreased in importance all together as it became associated with foreigners.

[35] While the legionaries were now recruited from the Italian communities south of the Po River, Rome had to rely on its non-Roman allies and clients to provide cavalry and light infantry.

He subjected his men to dangerous winter marches and relied heavily on the crafting skill of Romans in quickly building siege weapons and fortifications.

[45] Once the pilum struck a hard surface, the unhardened iron shank would buckle under the weight of the shaft; this prevented the enemy from throwing it back.

The pilum's narrow point, long shank, and heavy weight meant that a hit on an enemy shield would often pierce through and strike the defender.

[49] Both types were originally derived from Gallic designs and featured cheek and neck guards that offered protection to the face and head without obstructing the soldier's hearing and vision.

[49] The Coolus helmet featured wider cheek and neck guards than the Montefortino type, and generally had a reinforcing peak to the front to protect its user against blows from that direction.

A large emphasis was always placed on maintaining the ranks, not fleeing, not breaking away to attack on impulse, and keeping enough space between men so as not to inhibit range of motion.

Beatings to death with a wooden club (fustuarium) were administered to any soldier who was caught stealing from the camp, gave false witness, left his post, or discarded his armor or some other piece of equipment.

In a measure known as decimatio, one-tenth of a group or unit found guilty of offenses such as desertion or cowardice was randomly chosen by lot and executed.