Gladiator

[7] Tomb frescoes from the Campanian city of Paestum (4th century BC) show paired fighters, with helmets, spears and shields, in a propitiatory funeral blood-rite that anticipates early Roman gladiator games.

[16] In 216 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, late consul and augur, was honoured by his sons with three days of munera gladiatoria in the Forum Romanum, using twenty-two pairs of gladiators.

It involved three days of funeral games, 120 gladiators, and public distribution of meat (visceratio data)[20]—a practice that reflected the gladiatorial fights at Campanian banquets described by Livy and later deplored by Silius Italicus.

[34] He had more available in Capua but the senate, mindful of the recent Spartacus revolt and fearful of Caesar's burgeoning private armies and rising popularity, imposed a limit of 320 pairs as the maximum number of gladiators any citizen could keep in Rome.

[39] Following Caesar's assassination and the Roman Civil War, Augustus assumed imperial authority over the games, including munera, and formalised their provision as a civic and religious duty.

[42] Throughout the empire, the greatest and most celebrated games would now be identified with the state-sponsored imperial cult, which furthered public recognition, respect and approval for the emperor's divine numen, his laws, and his agents.

He was said to have restyled Nero's colossal statue in his own image as "Hercules Reborn", dedicated to himself as "Champion of secutores; only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times one thousand men.

Other highlighted features could include details of venationes, executions, music and any luxuries to be provided for the spectators, such as an awning against the sun, water sprinklers, food, drink, sweets and occasionally "door prizes".

For enthusiasts and gamblers, a more detailed program (libellus) was distributed on the day of the munus, showing the names, types and match records of gladiator pairs, and their order of appearance.

A crude Pompeian graffito suggests a burlesque of musicians, dressed as animals named Ursus tibicen (flute-playing bear) and Pullus cornicen (horn-blowing chicken), perhaps as accompaniment to clowning by paegniarii during a "mock" contest of the ludi meridiani.

Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected;[106] they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down.

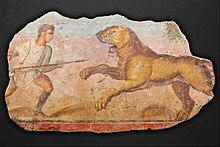

[108][88] The Zliten mosaic in Libya (circa 80–100 AD) shows musicians playing an accompaniment to provincial games (with gladiators, bestiarii, or venatores and prisoners attacked by beasts).

An outstanding fighter might receive a laurel crown and money from an appreciative crowd but for anyone originally condemned ad ludum the greatest reward was manumission (emancipation), symbolised by the gift of a wooden training sword or staff (rudis) from the editor.

"[112] A gladiator could acknowledge defeat by raising a finger (ad digitum), in appeal to the referee to stop the combat and refer to the editor, whose decision would usually rest on the crowd's response.

[125] The body of a gladiator who had died well was placed on a couch of Libitina and removed with dignity to the arena morgue, where the corpse was stripped of armour, and probably had its throat cut as confirmation of death.

[128] The bodies of noxii, and possibly some damnati, were thrown into rivers or dumped unburied;[129] Denial of funeral rites and memorial condemned the shade (manes) of the deceased to restless wandering upon the earth as a dreadful larva or lemur.

[130] Ordinary citizens, slaves and freedmen were usually buried beyond the town or city limits, to avoid the ritual and physical pollution of the living; professional gladiators had their own, separate cemeteries.

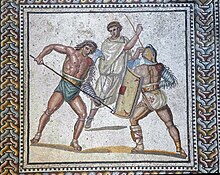

[133][134] A wealthy editor might commission artwork to celebrate a particularly successful or memorable show, and include named portraits of winners and losers in action; the Borghese Gladiator Mosaic is a notable example.

[145] No such stigma was attached to a gladiator owner (munerarius or editor) of good family, high status and independent means;[146] Cicero congratulated his friend Atticus on buying a splendid troop—if he rented them out, he might recover their entire cost after two performances.

[147] The Spartacus revolt had originated in a gladiator school privately owned by Lentulus Batiatus, and had been suppressed only after a protracted series of costly, sometimes disastrous campaigns by regular Roman troops.

[163] In Roman law, anyone condemned to the arena or the gladiator schools (damnati ad ludum) was a servus poenae (slave of the penalty), and was considered to be under sentence of death unless manumitted.

[183] Throughout Rome's history, some volunteers were prepared to risk loss of status or reputation by appearing in the arena, whether for payment, glory or, as in one recorded case, to revenge an affront to their personal honour.

His motives are unknown, but his voluntary and "shameless" arena appearance combined the "womanly attire" of a lowly retiarius tunicatus, adorned with golden ribbons, with the apex headdress that marked him out as a priest of Mars.

[188][189]Towards the end of the Republic, Cicero (Murena, 72–73) still describes gladiator shows as ticketed—their political usefulness was served by inviting the rural tribunes of the plebs, not the people of Rome en masse–but in Imperial times, poor citizens in receipt of the corn dole were allocated at least some free seating, possibly by lottery.

He assigned special seats to the married men of the commons, to boys under age their own section and the adjoining one to their preceptors; and he decreed that no one wearing a dark cloak should sit in the middle of the house.

[221] Silius Italicus wrote, as the games approached their peak, that the degenerate Campanians had devised the very worst of precedents, which now threatened the moral fabric of Rome: "It was their custom to enliven their banquets with bloodshed and to combine with their feasting the horrid sight of armed men [(Samnites)] fighting; often the combatants fell dead above the very cups of the revelers, and the tables were stained with streams of blood.

"[222] Death could be rightly meted out as punishment, or met with equanimity in peace or war, as a gift of fate; but when inflicted as entertainment, with no underlying moral or religious purpose, it could only pollute and demean those who witnessed it.

Courage, dignity, altruism and loyalty were morally redemptive; Lucian idealised this principle in his story of Sisinnes, who voluntarily fought as a gladiator, earned 10,000 drachmas and used it to buy freedom for his friend, Toxaris.

[226] Seneca had a lower opinion of the mob's un-Stoical appetite for ludi meridiani: "Man [is]...now slaughtered for jest and sport; and those whom it used to be unholy to train for the purpose of inflicting and enduring wounds are thrust forth exposed and defenceless.

"[198] These accounts seek a higher moral meaning from the munus, but Ovid's very detailed (though satirical) instructions for seduction in the amphitheatre suggest that the spectacles could generate a potent and dangerously sexual atmosphere.