Russian orthography

Russian spelling, which is mostly phonemic in practice, is a mix of morphological and phonetic principles, with a few etymological or historic forms, and occasional grammatical differentiation.

For example, the long adjective шарикоподшипниковый, sharikopodshipnikoviy [ʂa.rʲɪ.kə.pɐtˈʂɨ.pnʲɪ.kə.vɨj] ('pertaining to ball bearings'), may be decomposed as follows (words having independent existence in boldface): Note again that each component in the final production retains its basic form, despite the vowel reduction.

The fact that Russian has retained much of its ancient phonology has made the historical or etymological principle (dominant in languages like English, French, and Irish) less relevant.

), and ellipsis (…) are equivalent in shape to the basic symbols of punctuation (знаки препинания [ˈznakʲɪ prʲɪpʲɪˈnanʲɪjə]) used for the common European languages, and follow the same general principles of usage.

The hyphen is put between components of a word, and the em-dash to separate words in a sentence, in particular to mark longer appositions or qualifications that in English would typically be put in parentheses, and as a replacement for a copula: In short sentences describing a noun (but generally not a pronoun unless special poetic emphasis is desired) in present tense (as a substitution for a modal verb "быть/есть" (to be)): Quotes are not used to mark paragraphed direct quotation, which is instead separated out by the em-dash (—): Inlined direct speech and other quotation is marked at the first level by guillemets «», and by lowered and raised reversed double quotes („“) at the second: Unlike American English, the period or other terminal punctuation is placed outside the quotation.

The etymological inflexions are maintained by tradition and habit, although their non-phonetic spelling has occasionally prompted controversial calls for reform (as in the periods 1900–1910, 1960–1964).

In the past, uncertainty abounded about which of the ordinary or iotated/palatalizing series of vowels to allow after the sibilant consonants ⟨ж⟩ [ʐ], ⟨ш⟩ [ʂ], ⟨щ⟩ [ɕ:], ⟨ц⟩ [ts], ⟨ч⟩ [tɕ], which, as mentioned above, are not standard in their hard/soft pairs.

This problem, however, appears to have been resolved by applying the phonetic and grammatical principles (and to a lesser extent, the etymological) to define a complicated though internally consistent set of spelling rules.

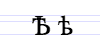

Russian orthography was simplified by unifying several adjectival and pronominal inflections, conflating the letter ѣ (Yat) with е, ѳ with ф, and і and ѵ with и. Additionally, the archaic mute yer became obsolete, including the ъ (the "hard sign") in final position following consonants (thus eliminating practically the last graphical remnant of the Old Slavonic open-syllable system).

[1][2] Although occasionally praised by the Russian working class, the reform was unpopular amongst the educated people, religious leaders and many prominent writers, many of whom were oppositional to the new state.

Because of this, the usage of the apostrophe as a dividing sign became widespread in place of ъ (e.g., под’ём, ад’ютант instead of подъём, адъютант), and came to be perceived as a part of the reform (even if, from the point of view of the letter of the decree of the Council of People's Commissars, such uses were mistakes).

The reform resulted in some economy in writing and typesetting, due to the exclusion of Ъ at the end of words—by the reckoning of Lev Uspensky, text in the new orthography was shorter by one-thirtieth.

Previously, the prefixes showed concurrence between phonetic (as now) and morphological (always з) spellings; at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century the standard rule was: с-, без-, ч(е)рез- were always written in this way; other prefixes ended with с before voiceless consonants except с and with з otherwise (разбить, разораться, разступиться, but распасться).