Sanskrit

[36] As the Rigveda was orally transmitted by methods of memorisation of exceptional complexity, rigour and fidelity,[37][38] as a single text without variant readings,[39] its preserved archaic syntax and morphology are of vital importance in the reconstruction of the common ancestor language Proto-Indo-European.

[8][10][43] In each of India's recent decennial censuses, several thousand citizens have reported Sanskrit to be their mother tongue,[g] but the numbers are thought to signify a wish to be aligned with the prestige of the language.

[47] From the late Vedic period onwards, state Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, resonating sound and its musical foundations attracted an "exceptionally large amount of linguistic, philosophical and religious literature" in India.

No written records from such an early period survive, if any ever existed, but scholars are generally confident that the oral transmission of the texts is reliable: they are ceremonial literature, where the exact phonetic expression and its preservation were a part of the historic tradition.

In particular that retroflex consonants did not exist as a natural part of the earliest Vedic language,[72] and that these developed in the centuries after the composition had been completed, and as a gradual unconscious process during the oral transmission by generations of reciters.

[86] According to Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton – Indologists known for their translation of the Ṛg-veda – the Vedic Sanskrit literature "clearly inherited" from Indo-Iranian and Indo-European times the social structures such as the role of the poet and the priests, the patronage economy, the phrasal equations, and some of the poetic metres.

[92] The Aṣṭādhyāyī was not the first description of Sanskrit grammar, but it is the earliest that has survived in full, and the culmination of a long grammatical tradition that Fortson says, is "one of the intellectual wonders of the ancient world".

As in this period the Indo-Aryan tribes had not yet made contact with the inhabitants of the South of the subcontinent, this suggests a significant presence of Dravidian speakers in North India (the central Gangetic plain and the classical Madhyadeśa) who were instrumental in this substratal influence on Sanskrit.

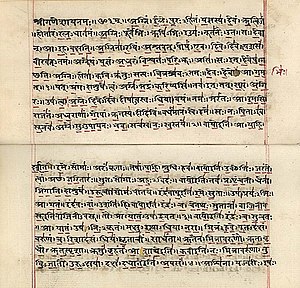

[135] Extant manuscripts in Sanskrit number over 30 million, one hundred times those in Greek and Latin combined, constituting the largest cultural heritage that any civilization has produced prior to the invention of the printing press.

[142][144] They speculated on the role of language, the ontological status of painting word-images through sound, and the need for rules so that it can serve as a means for a community of speakers, separated by geography or time, to share and understand profound ideas from each other.

[124] Some of these scholars of Indian history regionally produced vernacularized Sanskrit to reach wider audiences, as evidenced by texts discovered in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Maharashtra.

He dismisses the idea that Sanskrit declined due to "struggle with barbarous invaders", and emphasises factors such as the increasing attractiveness of vernacular language for literary expression.

[182] Similarly, Brian Hatcher states that the "metaphors of historical rupture" by Pollock are not valid, that there is ample proof that Sanskrit was very much alive in the narrow confines of surviving Hindu kingdoms between the 13th and 18th centuries, and its reverence and tradition continues.

A part of the difficulty is the lack of sufficient textual, archaeological and epigraphical evidence for the ancient Prakrit languages with rare exceptions such as Pali, leading to a tendency toward anachronistic errors.

Numerous North, Central, Eastern and Western Indian languages, such as Hindi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Nepali, Braj, Awadhi, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Marathi, and others belong to the New Indo-Aryan stage.

[138] Beyond ancient India, significant collections of Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions have been found in China (particularly the Tibetan monasteries),[195][196] Myanmar,[197] Indonesia,[198] Cambodia,[199] Laos,[200] Vietnam,[201] Thailand,[202] and Malaysia.

The affixes in Sanskrit are almost always suffixes, with exceptions such as the augment "a-" added as prefix to past tense verb forms and the "-na/n-" infix in single verbal present class, states Jamison.

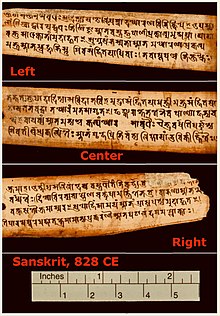

[261] However, the reliability of these lists has been questioned and the empirical evidence of writing systems in the form of Sanskrit or Prakrit inscriptions dated prior to the 3rd century BCE has not been found.

[262][w] According to Salomon, many find it difficult to explain the "evidently high level of political organization and cultural complexity" of ancient India without a writing system for Sanskrit and other languages.

[345] Krishnamurthi mentions that although it is not clear when the Sanskrit influence happened on the Dravidian languages, it might have been around the 5th century BCE at the time of separation of Tamil and Kannada from a common ancestral stage.

[citation needed] In ancient and medieval times, several Sanskrit words in the field of food and spices made their way into European languages including Greek, Latin and later English.

[365] Many Hindu rituals and rites-of-passage such as the "giving away the bride" and mutual vows at weddings, a baby's naming or first solid food ceremony and the goodbye during a cremation invoke and chant Sanskrit hymns.

[366] Major festivals such as the Durga Puja ritually recite entire Sanskrit texts such as the Devi Mahatmya every year particularly among the numerous communities of eastern India.

[389] Dmitri Mendeleev used the Sanskrit numbers of one, two and three (eka-, dvi- or dwi-, and tri- respectively) to give provisional names to his predicted elements, like eka-boron being Gallium or eka-Francium being Ununennium.

[394][395][396] European scholarship in Sanskrit, begun by Heinrich Roth (1620–1668) and Johann Ernst Hanxleden (1681–1731), is considered responsible for the discovery of an Indo-European language family by Sir William Jones (1746–1794).

[397] The 18th- and 19th-century speculations about the possible links of Sanskrit to ancient Egyptian language were later proven to be wrong, but it fed an orientalist discourse both in the form Indophobia and Indophilia, states Trautmann.

[398] Sanskrit writings, when first discovered, were imagined by Indophiles to potentially be "repositories of the primitive experiences and religion of the human race, and as such confirmatory of the truth of Christian scripture", as well as a key to "universal ethnological narrative".

[399]: 96–97 The Indophobes imagined the opposite, making the counterclaim that there is little of any value in Sanskrit, portraying it as "a language fabricated by artful [Brahmin] priests", with little original thought, possibly copied from the Greeks who came with Alexander or perhaps the Persians.

This launched the Asiatic Society, an idea that was soon transplanted to Europe starting with the efforts of Henry Thomas Colebrooke in Britain, then Alexander Hamilton who helped expand its studies to Paris and thereafter his student Friedrich Schlegel who introduced Sanskrit to the universities of Germany.

[410] Composer John Williams featured choirs singing in Sanskrit for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.

Saṃ-skṛ-ta

Saṃ-skṛ-ta

Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhana , 532 CE. [ 115 ]