Salon d'Automne

[1] Perceived as a reaction against the conservative policies of the official Paris Salon, this massive exhibition almost immediately became the showpiece of developments and innovations in 20th-century painting, drawing, sculpture, engraving, architecture and decorative arts.

The aim of the salon was to encourage the development of the fine arts, to serve as an outlet for young artists (of all nationalities), and a platform to broaden the dissemination of Impressionism and its extensions to a popular audience.

The Salon d'Automne is distinguished by its multidisciplinary approach, open to paintings, sculptures, photographs (from 1904), drawings, engravings, applied arts, and the clarity of its layout, more or less per school.

Retaliating in defense of Jourdain, Eugène Carrière (a respected artistic figure) issued a statement that if forced to choose, he would join the Salon d'Automne and resign from the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

[5] After viewing the boldly colored canvases of Henri Matisse, André Derain, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Charles Camoin, and Jean Puy at the Salon d'Automne of 1905, the critic Louis Vauxcelles disparaged the painters as "fauves" (wild beasts), thus giving their movement the name by which it became known, Fauvism.

[12] Pinchon's paintings of this period are closely related to the Post-Impressionist and Fauvist styles, with golden yellows, incandescent blues, a thick impasto and larger brushstrokes.

[11] At the exhibition of 1910, held from 1 October to 8 November at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Paris, Jean Metzinger introduced an extreme form of what would soon be labeled 'Cubism', not just to the general public for the first time, but to other artists that had no contact with Picasso or Braque.

Though others were already working in a proto-Cubist vein with complex Cézannian geometries and unconventional perspectives, Metzinger's Nu à la cheminée (Nude) represented a radical departure further still.

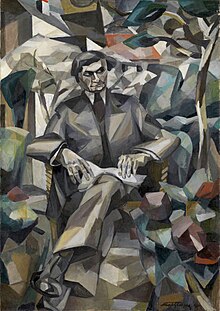

(Albert Gleizes, 1925)[19]In a review of the Salon, the poet Roger Allard (1885-1961) announces the appearance of a new school of French painters concentrating their attention on form rather than on color.

Following this salon Metzinger wrote the article Notes sur la peinture,[21] in which he compares the similarities in the works Picasso, Braque, Delaunay, Gleizes and Le Fauconnier.

This scandal, in addition to the non-French status of the authors in a time of growing nationalism, aroused the old polemic of exhibiting low-cost production objects, mass-produced items, simply designed furniture and interior decoration, in the context of a salon dedicated to art.

The effects would be felt in Paris, first with the 1912 exhibition of French decorative arts at the Pavillon de Marsan, then again at the Salon d'Automne of 1912, with La Maison Cubiste,[2][23] the collaborative effort of the designer André Mare, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and other artists associated with the Section d'Or.

[24] In Room 7 and 8 of the 1911 Salon d'Automne, held 1 October through November 8, at the Grand Palais in Paris, hung works by Metzinger (Le goûter (Tea Time)), Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Albert Gleizes, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp, František Kupka, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky and Francis Picabia.

From which it became clear that these paintings - and I specify the names of the painters who were, alone, the reluctant causes of all this frenzy: Jean Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and myself - appeared as a threat to an order that everyone thought had been established forever.

What had begun as a question of aesthetics quickly turned political during the Cubist exhibition, and as in the 1905 Salon d'Automne, the critic Louis Vauxcelles (in Les Arts..., 1912) was most implicated in the deliberations.

It was also Vauxcelles who, on the occasion of the 1910 Salon des Indépendants, wrote disparagingly of 'pallid cubes' with reference to the paintings of Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Léger and Delaunay.

[30][31] In his 1921 essay on the Salon d'Automne, published in Les Echos (p. 23), founder Frantz Jourdain denouncing aesthetic snobbery, writes that the saber-rattling revolutionaries dubbed the Cubists, Futurists and Dadaists were actually crusty reactionaries who scorned modern progress and revealed contempt for democracy, science, industry and commerce.

[32] Jourdain again came under vicious attack in 1912—as the French nation drew closer to war in a conservative and fiercely nationalistic political climate—now by the dean of the Conseil Municipal and member of the city's Commission des Beaux-Arts, Jean Pierre Philippe Lampué.

The huge scandal prompted the critic Roger Allard to defend Jourdain and the Cubists in the journal La Côte, pointing out that it wasn't the first time the Salon d'Automne—as a venue to promote modern art—came under attack by city officials, the Institute, and members of the Conseil.

[2] The Salon d'Automne from its very inception was one of the most significant avant-garde venues, exhibiting not just painting, drawing and sculpture, but industrial design, urbanism, photography, new developments in music and cinema.

[33] To appease the French, Jourdain invited the pontiffs des Artistes Français, writes Gleizes, to an "exposition de portraits" specially organized at the salon.

Breton, with the support of Charles Benoist, accused the French government of sponsoring the excesses of the Cubists by virtue of providing an exhibition space at the Grand Palais.

In the house were hung cubist paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Roger de La Fresnaye, and Jean Metzinger (Woman with a Fan, 1912).

While the geometric decoration of the plaster façade and the paintings were inspired by cubism, the furnishings, carpets, cushions, and wallpapers by André Mare were the beginning of a distinct new style, Art Deco.

[41] La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished house, with a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Metzinger (Woman with a Fan), Gleizes, Laurencin and Léger were hung—and a bedroom.

[17] The preface of the catalog was written by the French Socialist politician Marcel Sembat who a year earlier—against the outcry of Jules-Louis Breton regarding the use of public funds to provide the venue (at the Salon d'Automne) to exhibit 'barbaric' art—had defended the Cubists, and freedom of artistic expression in general, in the National Assembly of France.

(Marcel Sembat)[47]This exhibition too made its flashing appearance in the news, when a nude by Kees van Dongen entitled The Spanish Shawl (Woman with Pigeons or The Beggar of Love) was ordered by the police to be removed from the Salon d'Automne.

In addition to painting and sculpture, the Salon included works in the decorative arts such as the glassworks of René Lalique, Julia Bathory as well as architectural designs by Le Corbusier.

Fearing that Cubism would not be taken seriously in such public exhibitions where thousands of spectators would assemble to see new creations, he signed exclusivity contracts with his artists, ensuring that their works could only be shown (and sold) in the privacy of his own gallery.

The exhibition however, was "marred by disturbances that have remained unattributed" according to Michèle C. Cone (New York-based critic and historian, author of French Modernisms: Perspectives on Art before, during and after Vichy, Cambridge 2001).