Symbiogenesis

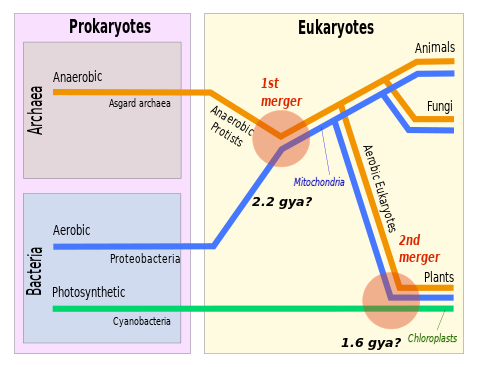

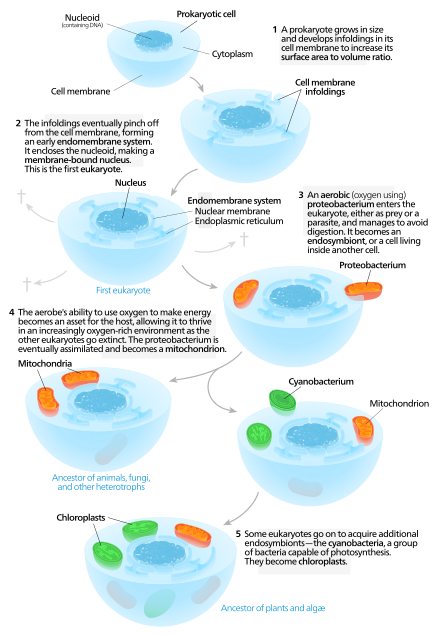

[3] The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibly other organelles of eukaryotic cells are descended from formerly free-living prokaryotes (more closely related to the Bacteria than to the Archaea) taken one inside the other in endosymbiosis.

The endosymbiotic theory was articulated in 1905 and 1910 by the Russian botanist Konstantin Mereschkowski, and advanced and substantiated with microbiological evidence by Lynn Margulis in 1967.

[5][6][7] Mereschkowski proposed that complex life-forms had originated by two episodes of symbiogenesis, the incorporation of symbiotic bacteria to form successively nuclei and chloroplasts.

[8] In 1918 the French scientist Paul Jules Portier published Les Symbiotes, in which he claimed that the mitochondria originated from a symbiosis process.

Christian de Duve proposed that the peroxisomes may have been the first endosymbionts, allowing cells to withstand growing amounts of free molecular oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.

[33] Taking into account the entire original endosymbiont genome, there are three main possible fates for genes over evolutionary time.

Nuclear copies of some mitochondrial genes, however, do not contain organelle-specific splice sites, suggesting a processed mRNA intermediate.

[25][34] According to this hypothesis, disturbances to organelles, including autophagy (normal cell destruction), gametogenesis (the formation of gametes), and cell stress release DNA which is imported into the nucleus and incorporated into the nuclear DNA using non-homologous end joining (repair of double stranded breaks).

[34] For example, in the initial stages of endosymbiosis, due to a lack of major gene transfer, the host cell had little to no control over the endosymbiont.

A similar mechanism is thought to occur in tobacco plants, which show a high rate of gene transfer and whose cells contain multiple chloroplasts.

[37] Endosymbiotic theory for the origin of mitochondria suggests that the proto-eukaryote engulfed a protomitochondrion, and this endosymbiont became an organelle, a major step in eukaryogenesis, the creation of the eukaryotes.

[39] The presence of DNA in mitochondria and proteins, derived from mtDNA, suggest that this organelle may have been a prokaryote prior to its integration into the proto-eukaryote.

[41] The process of symbiogenesis by which the early eukaryotic cell integrated the proto-mitochondrion likely included protection of the archaeal host genome from the release of reactive oxygen species.

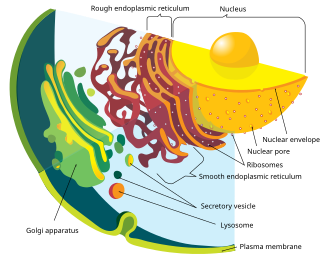

[41] Interaction of internal components of vesicles may have led to the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, both being parts of the endomembrane system.

[41] The syntrophy hypothesis, proposed by López-García and Moreira around the year 2000, suggested that eukaryotes arose by combining the metabolic capabilities of an archaean, a fermenting deltaproteobacterium, and a methanotrophic alphaproteobacterium which became the mitochondrion.

In 2020, the same team updated their syntrophy proposal to cover an Asgard archaean that produced hydrogen with deltaproteobacterium that oxidised sulphur.

A third organism, an alphaproteobacterium able to respire both aerobically and anaerobically, and to oxidise sulphur, developed into the mitochondrion; it may possibly also have been able to photosynthesise.

The oldest known body fossils that can be positively assigned to the Eukaryota are acanthomorphic acritarchs from the 1.631 Gya Deonar Formation of India.

Molecular clocks have also been used to estimate the last eukaryotic common ancestor, however these methods have large inherent uncertainty and give a wide range of dates.

[54] A 2.3 Gya estimate[55] also seems reasonable, and has the added attraction of coinciding with one of the most pronounced biogeochemical perturbations in Earth history, the early Palaeoproterozoic Great Oxygenation Event.

The marked increase in atmospheric oxygen concentrations at that time has been suggested as a contributing cause of eukaryogenesis, inducing the evolution of oxygen-detoxifying mitochondria.

[56] Alternatively, the Great Oxidation Event might be a consequence of eukaryogenesis, and its impact on the export and burial of organic carbon.

There are many hypotheses to explain why organelles retain a small portion of their genome; however no one hypothesis will apply to all organisms, and the topic is still quite controversial.

The time delay involved in signalling the nucleus and transporting a cytosolic protein to the organelle results in the production of damaging reactive oxygen species.

Secondary endosymbiosis has occurred several times and has given rise to extremely diverse groups of algae and other eukaryotes.

Some organisms can take opportunistic advantage of a similar process, where they engulf an alga and use the products of its photosynthesis, but once the prey item dies (or is lost) the host returns to a free living state.

A secondary endosymbiosis event involving an ancestral red alga and a heterotrophic eukaryote resulted in the evolution and diversification of several other photosynthetic lineages including Cryptophyta, Haptophyta, Stramenopiles (or Heterokontophyta), and Alveolata.

This organism behaves like a predator until it ingests a green alga, which loses its flagella and cytoskeleton but continues to live as a symbiont.

Hatena meanwhile, now a host, switches to photosynthetic nutrition, gains the ability to move towards light, and loses its feeding apparatus.