Serpin

1by7A:1-415 1ovaA:1-385 1uhgA:1-385 1jtiB:1-385 1attB:77-433 1nq9L:76-461 1oyhI:76-461 1e03L:76-461 1e05I:76-461 1br8L:76-461 1r1lL:76-461 1lk6L:76-461 1antL:76-461 2behL:76-461 1dzhL:76-461 1athA:78-461 1tb6I:76-461 2antI:76-461p 1dzgI:76-461 1azxL:76-461 1jvqI:76-461 1sr5A:76-461 1e04I:76-461 1xqgA:1-375 1xu8B:1-375 1wz9B:1-375 1xqjA:1-375 1c8oA:1-300 1m93A:1-55 1f0cA:1-305 1k9oI:18-392 1sek :18-369 1atu :45-415 1ezxB:383-415 8apiA:43-382 1qmbA:49-376 1iz2A:43-415 1oo8A:43-415 1d5sB:378-415 7apiA:44-382 1qlpA:43-415 1ophA:43-415 1kct :44-415 2d26A:43-382 9apiB:383-415 1psi :47-415 1hp7A:43-415 3caaA:50-383 1qmnA:43-420 4caaB:390-420 2achA:47-383 1as4A:48-383 1yxaB:42-417 1lq8F:376-406 2paiB:374-406 1paiB:374-406 1jmoA:119-496 1jmjA:119-496 1oc0A:25-402 1dvnA:25-402 1b3kD:25-402 1dvmD:25-402 1a7cA:25-402 1c5gA:25-402 1db2B:26-402 9paiA:25-402 1lj5A:25-402 1m6qA:138-498 1jjoD:101-361 Serpins are a superfamily of proteins with similar structures that were first identified for their protease inhibition activity and are found in all kingdoms of life.

[8][9] Protease inhibition by serpins controls an array of biological processes, including coagulation and inflammation, and consequently these proteins are the target of medical research.

[7][8] The conformational-change mechanism confers certain advantages, but it also has drawbacks: serpins are vulnerable to mutations that can result in serpinopathies such as protein misfolding and the formation of inactive long-chain polymers.

[11][12] Serpin polymerisation not only reduces the amount of active inhibitor, but also leads to accumulation of the polymers, causing cell death and organ failure.

[1] Protease inhibitory activity in blood plasma was first reported in the late 1800s,[13] but it was not until the 1950s that the serpins antithrombin and alpha 1-antitrypsin were isolated,[14] with the subsequent recognition of their close family homology in 1979.

[18] The initial characterisation of the new family centred on alpha1-antitrypsin, a serpin present in high concentration in blood plasma, the common genetic disorder of which was shown to cause a predisposition to the lung disease emphysema[19] and to liver cirrhosis.

[28] This active-centre specificity of inhibition was also evident in the many other families of protease inhibitors[7] but the serpins differed from them in being much larger proteins and also in possessing what was soon apparent as an inherent ability to undergo a change in shape.

Subsequent structural studies have revealed an additional advantage of the conformational mechanism[34] in allowing the subtle modulation of inhibitory activity, as notably seen at tissue level[35] with the functionally diverse serpins in human plasma.

[44][45][46] Approximately two-thirds of human serpins perform extracellular roles, inhibiting proteases in the bloodstream in order to modulate their activities.

For example, extracellular serpins regulate the proteolytic cascades central to blood clotting (antithrombin), the inflammatory and immune responses (antitrypsin, antichymotrypsin, and C1-inhibitor) and tissue remodelling (PAI-1).

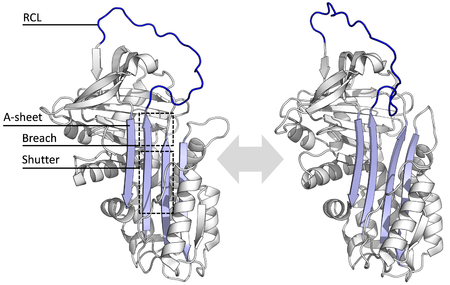

Structures have been solved showing the RCL either fully exposed or partially inserted into the A-sheet, and serpins are thought to be in dynamic equilibrium between these two states.

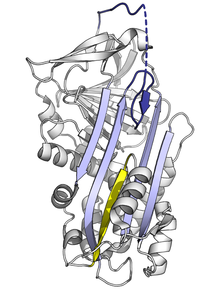

The conformational change involves the RCL moving to the opposite end of the protein and inserting into β-sheet A, forming an extra antiparallel β-strand.

[7] The efficiency of inhibition depends on fact that the relative kinetic rate of the conformational change is several orders of magnitude faster than hydrolysis by the protease.

The X-ray crystal structures of antithrombin, heparin cofactor II, MENT and murine antichymotrypsin reveal that these serpins adopt a conformation wherein the first two amino acids of the RCL are inserted into the top of the A β-sheet.

Upon binding a high-affinity pentasaccharide sequence within long-chain heparin, antithrombin undergoes a conformational change, RCL expulsion, and exposure of the P1 arginine.

Understanding of the molecular basis of this interaction enabled the development of Fondaparinux, a synthetic form of Heparin pentasaccharide used as an anti-clotting drug.

One mechanism by which this occurs in mammals is via the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), which binds to inhibitory complexes made by antithrombin, PA1-1, and neuroserpin, causing cellular uptake.

[73][74] Similarly, the Drosophila necrotic serpin is degraded in the lysosome after being trafficked into the cell by the Lipophorin Receptor-1 (homologous to the mammalian LDL receptor family).

[11][77] Since the stressed serpin fold is high-energy, mutations can cause them to incorrectly change into their lower-energy conformations (e.g. relaxed or latent) before they have correctly performed their inhibitory role.

[10] Mutations that affect the rate or the extent of RCL insertion into the A-sheet can cause the serpin to undergo its S to R conformational change before having engaged a protease.

[10][78] Similarly, mutations that promote inappropriate transition to the monomeric latent state cause disease by reducing the amount of active inhibitory serpin.

The bottom half of the sheet is filled as a result of one of the α-helices (the F-helix) partially switching to a β-strand conformation, completing the β-sheet hydrogen bonding.

[83] In some rare cases, a single amino acid change in a serpin's RCL alters its specificity to target the wrong protease.

[86] Domain-swaps occur when mutations or environmental factors interfere with the final stages of serpin folding to the native state, causing high-energy intermediates to misfold.

[86] The domain-swapped trimer (of antitrypsin) forms via the exchange of an entirely different region of the structure, the B-sheet (with each molecule's RCL inserted into its own A-sheet).

[84][89] These domain-swapped dimer and trimer structures are thought to be the building blocks of the disease-causing polymer aggregates, but the exact mechanism is still unclear.

[98] Exceptions include the intracellular heat shock serpin HSP47, which is a chaperone essential for proper folding of collagen, and cycles between the cis-Golgi and the endoplasmic reticulum.

[48][189][190] In Tenebrio molitor (a large beetle), a protein (SPN93) comprising two discrete tandem serpin domains functions to regulate the toll proteolytic cascade.

The RCL of several serpins from wheat grain and rye contain poly-Q repeat sequences similar to those present in the prolamin storage proteins of the endosperm.

Dockerins are commonly found in proteins that localise to the fungal cellulosome, a large extracellular multiprotein complex that breaks down cellulose.