Reputation of William Shakespeare

[citation needed] Then the emphasis was placed on the soliloquies as declamatory turns at the expense of pace and action, and Shakespeare's plays seemed in peril of disappearing beneath the added music, scenery, and special effects produced by thunder, lightning, and wave machines.

Editors and critics of the plays, disdaining the showiness and melodrama of Shakespearean stage representation, began to focus on Shakespeare as a dramatic poet, to be studied on the printed page rather than in the theatre.

To the later 19th century, Shakespeare became in addition an emblem of national pride, the crown jewel of English culture, and a "rallying-sign", as Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1841, for the whole British Empire.

He was included in some contemporary lists of leading poets, but he seems to have lacked the stature of the aristocratic Philip Sidney, who became a cult figure due to his death in battle at a young age, or of Edmund Spenser.

[citation needed] Though denied the use of the stage, costumes and scenery, actors still managed to ply their trade by performing "drolls" or short pieces of larger plays that usually ended with some type of jig.

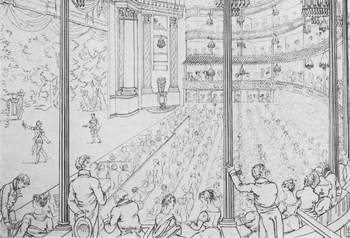

In the elaborate Restoration London playhouses, designed by Christopher Wren, Shakespeare's plays were staged with music, dancing, thunder, lightning, wave machines, and fireworks.

A notorious example is Irish poet Nahum Tate's happy-ending King Lear (1681) (which held the stage until 1838), while The Tempest was turned into an opera replete with special effects by William Davenant.

[1] The modern view of the Restoration stage as the epitome of Shakespeare abuse and bad taste has been shown by Hume to be exaggerated, and both scenery and adaptation became more reckless in the 18th and 19th centuries.

This occasion was a striking example of the growing prominence of Shakespeare stars in the theatrical culture, the big attraction being the competition and rivalry between the male leads at Covent Garden and Drury Lane, Spranger Barry and David Garrick.

In 1995, the American journalist Stephen Kinzer writing in The New York Times observed: "Shakespeare is an all-but-guaranteed success in Germany, where his work has enjoyed immense popularity for more than 200 years.

Until this moment, the most admired English poets were Alexander Pope, John Milton, James Thomson and Thomas Gray and their texts had already been translated into French.

In the first half of the century, French intellectuals who had visited or sojourned in England for a period of time and, therefore, had had the opportunity to see theatrical representations of English plays, began to express their opinions and judgments on Shakespeare and his theatre.

Eventually, innovations infiltrated into French theatre and when Voltaire presented La Mort de Cèsar to his audience in 1743, he was able to represent Caesar's death as he had originally imagined it.

On one hand, Italian intellectuals who sojourned for a period of time in England had the possibility to witness theatrical representations and to write about their experiences; their texts, then, travelled back to Italy.

Giuseppe Baretti published Discours sur Shakespeare et M.r de Voltaire in 1777; Alessandro Verri translated Hamlet and Othello between 1769 and 1777; Francesco Algarotti, who did not appreciate English theatre, changed his mind when he saw a representation of Julius Caesar in London.

[25] Theatres and theatrical scenery became ever more elaborate in the 19th century, and the acting editions used were progressively cut and restructured to emphasise more and more the soliloquies and the stars, at the expense of pace and action.

Through the 19th century, a roll call of legendary actors' names all but drown out the plays in which they appear: Sarah Siddons (1755–1831), John Philip Kemble (1757–1823), Henry Irving (1838–1905), and Ellen Terry (1847–1928).

The belief in the unappreciated 18th-century Shakespeare was proposed at the beginning of the 19th century by the Romantics, in support of their view of 18th-century literary criticism as mean, formal, and rule-bound, which was contrasted with their own reverence for the poet as prophet and genius.

As the concept of literary originality grew in importance, critics were horrified at the idea of adapting Shakespeare's tragedies for the stage by putting happy endings on them, or editing out the puns in Romeo and Juliet.

As the foremost of the great canonical writers, the jewel of English culture, and as Carlyle puts it, "merely as a real, marketable, tangibly useful possession", Shakespeare became in the 19th century a means of creating a common heritage for the motherland and all her colonies.

Rodney Symington, Professor of Germanic and Russian Studies at the University of Victoria, Canada, deals with this question in The Nazi Appropriation of Shakespeare: Cultural Politics in the Third Reich (Edwin Mellen Press, 2005).

Of this play, one critic wrote: "If the courtier Laertes is drawn to Paris and the humanist Horatio seems more Roman than Danish, it is surely no accident that Hamlet's alma mater should be Wittenberg."

A leading magazine declared that the crime which deprived Hamlet of his inheritance was a foreshadowing of the Treaty of Versailles, and that the conduct of Gertrude was reminiscent of the "spineless" Weimar politicians.

Weeks after Hitler took power in 1933, an official party publication appeared, entitled Shakespeare – a Germanic Writer, a counter to those who wanted to ban all foreign influences.

[30] Hamlet (1964) by Grigori Kozintsev portrayed 16th century Denmark as a dark, gloomy and oppressive place, with recurring images of imprisonment, these marking the film from the focus on the portcullis of Elsinore to the iron corset Ophelia is forced to wear as she goes insane.

[36] The play's director, the Shakespearean scholar Fang Ping, who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution for studying this "bourgeois Western imperialist", stated in an interview at the time that King Lear was relevant in China because King Lear, the "highest ruler of a monarchy", created a world full of cruelty and chaos where those who loved him were punished and those who did not were rewarded, a barely veiled reference to the often capricious behavior of Mao, who punished his loyal followers for no apparent reason.

[37] A 1981 production of The Merchant of Venice was a hit with Chinese audiences, as the play was seen to promote the theme of justice and fairness in life, with the character of Portia being especially popular, as she is seen as standing for, as one critic wrote, "the humanist spirit of the Renaissance" with its striving for "individuality, human rights and freedom".

[38] Unlike in Western productions, the character of Shylock is presented very much as an unnuanced villain, capable only of envy, spite, greed and cruelty, a man whose actions are only motivated by his spiritual impoverishment.

Shakespeare's reputation continues to have an influence on the film industry, with new versions of his works, such as The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021), directed by Joel Coen, being put into production.

[citation needed] Shakespeare's plays (especially A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Merchant of Venice and Julius Caesar) continue to be taught in numerous English-speaking schools globally, and have been translated into different languages.