Sherman's March to the Sea

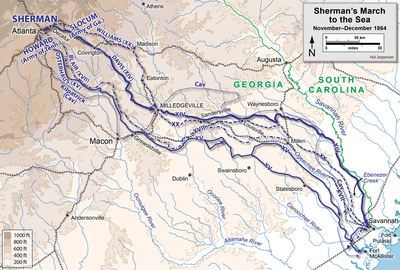

The campaign began on November 15 with Sherman's troops leaving Atlanta, recently taken by Union forces, and ended with the capture of the port of Savannah on December 21.

His forces followed a "scorched earth" policy, destroying military targets as well as industry, infrastructure, and civilian property, disrupting the Confederacy's economy and transportation networks.

He and the Union Army's commander, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, believed that the Civil War would come to an end only if the Confederacy's strategic capacity for warfare could be decisively broken.

In planning for the march, Sherman used livestock and crop production data from the 1860 United States census to lead his troops through areas where he believed they would be able to forage most effectively.

As for horses, mules, wagons, &c., belonging to the inhabitants, the cavalry and artillery may appropriate freely and without limit, discriminating, however, between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.

In all foraging, of whatever kind, the parties engaged will refrain from abusive or threatening language, and may, where the officer in command thinks proper, give written certificates of the facts, but no receipts, and they will endeavor to leave with each family a reasonable portion for their maintenance.

An army of individuals trained in the school of experience to look after their own food and health, to march far and fast with the least fatigue, to fight with the least exposure, above all, to act swiftly and to work thoroughly.

Considering Sherman's military priorities, however, this tactical maneuver by his enemy to get out of his force's path was welcomed to the point of remarking, "If he will go to the Ohio River, I'll give him rations.

Away off in the distance, on the McDonough road, was the rear of Howard's column, the gun-barrels glistening in the sun, the white-topped wagons stretching away to the south; and right before us the Fourteenth Corps, marching steadily and rapidly, with a cheery look and swinging pace, that made light of the thousand miles that lay between us and Richmond.

done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.Sherman's personal escort on the march was the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment, a unit made up entirely of Southerners who remained loyal to the Union.

The two wings of the army attempted to confuse and deceive the enemy about their destinations; the Confederates could not tell from the initial movements whether Sherman would march on Macon, Augusta, or Savannah.

Howard's wing, led by Kilpatrick's cavalry, marched south along the railroad to Lovejoy's Station, which caused the defenders there to conduct a fighting retreat to Macon.

Gen. Charles C. Walcutt arrived to stabilize the defense, and the division of Georgia militia launched several hours of badly coordinated attacks, eventually retreating with about 1,100 casualties (of which about 600 were prisoners), versus the Union's 100.

On November 23, Slocum's troops captured the city and held a mock legislative session in the capitol building, jokingly voting Georgia back into the Union.

Overnight, Union engineers constructed a bridge 2 miles (3.2 km) away from the bluff across the Oconee River, and 200 soldiers crossed to flank the Confederate position.

Sherman's armies reached the outskirts of Savannah on December 10 but found that Hardee had entrenched 10,000 men in favorable fighting positions, and his soldiers had flooded the surrounding rice fields, leaving only narrow causeways available to approach the city.

Now that Sherman had contact with the Navy fleet under Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, he was able to obtain the supplies and siege artillery he required to invest Savannah.

[24][better source needed] Sherman telegraphed to President Lincoln, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.

Not only does it afford the obvious and immediate military advantages; but, in showing to the world that your army could be divided, putting the stronger part to an important new service, and yet leaving enough to vanquish the old opposing force of the whole—Hood's army—it brings those who sat in darkness, to see a great light.

Please make my grateful acknowledgments to your whole army, officers and men.The March attracted a huge number of refugees, to whom Sherman assigned land with his Special Field Orders No.

[29] From Savannah, after a month-long delay for rest, Sherman marched north in the spring in the Carolinas Campaign, intending to complete his turning movement and combine his armies with Grant's against Robert E. Lee.

[35] Military historians Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones cited the significant damage wrought to railroads and Southern logistics in the campaign and stated that "Sherman's raid succeeded in 'knocking the Confederate war effort to pieces'.

Hundreds of African Americans drowned trying to cross in Ebenezer Creek north of Savannah while attempting to follow Sherman's Army in its March to the Sea.

"[48] One example of an outspoken exponent of the "hard war" classification was W. Todd Groce, President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Georgia Historical Society.

In his publications, Groce focused on the March to the Sea, contending that "it lacked the wholesale destruction of human life that characterized World War II" and that "Sherman's primary targets – foodstuffs and industrial, government and military property – were carefully chosen to create the desired effect, and never included mass killing of civilians."

"[49] The sole exception to Groce's focus on the March to the Sea was evidence for his contention that Sherman fought "to bring rebels back into the Union, not to annihilate them."

According to Groce, Sherman "told one South Carolina woman that he was ransacking her plantation so that her soldier husband would come home and Grant would not have to kill him in the trenches at Petersburg.

[54][55][56][53] During the South Carolina stage of the so-called "March North from the Sea",[57] historian Lisa Tendrich Frank maintained, Union soldiers had "earned a reputation for being 'rather loose on the handle.'

The records of Sherman's punitive actions in North Carolina revealed that punishments were commensurate with the conditions of Confederate rape victims, as well as the number of sexual assaults by a given perpetrator.

"[50] Conversely, for scholars who advanced an indiscriminate consequentialism against noncombatants, especially Confederate ones, as key to expediting abolition and winning the war, "why should we not simply acknowledge the circumstances, rather than be embarrassed by them or try to cloak them in euphemisms?