Small clause

In linguistics, a small clause consists of a subject and its predicate, but lacks an overt expression of tense.

The small clause is related to the phenomena of raising-to-object, exceptional case-marking, accusativus cum infinitivo, and object control.

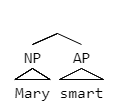

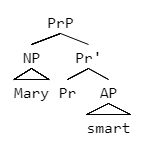

[2] Timothy Stowell in 1981 analyzed the small clause as a constituent,[6] and proposed a structure using X-bar theory.

[9] In each example, the posited small clause is in boldface, and the underlined expression functions as a predicate over the nominal immediately to its left, which is the subject.

The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the Government and Binding framework and its tradition, for examples see Chomsky,[17] Ouhalla,[11] Culicover,[16]: p47 Haegeman and Guéron.

From this evidence, some linguists have theorized that the subjects of adjectival and verbal small clauses must differ in syntactic position.

This conclusion is bolstered by the knowledge that verbal and adjectival small clauses differ in their predication forms.

The latter approach proposes that small clauses lack inflected tense but can have a bare infinitival verb.

The following two examples show how the argument structure of the verb "consider" affects what predicate can be in the small clause.

[38] However, this theory of selectional requirement is also disputed, as substitution of different small clauses can create grammatical readings.

This suggests that the semantic relation of the main verb and the small clause affects sentences' grammaticality.

In such cases, the matrix verb appears to be subcategorizing for its object noun (phrase), which then functions as the subject of the small clause.

In this regard, there are a number of observations suggesting that the object/subject noun phrase is a direct dependent of the matrix verb.

This captures that fact, with such object/subject noun phrases, as illustrated in (47), the small clause generally does not behave as a single constituent with respect to movement diagnostics.

Thus, the "subject" of a small clause cannot participate in topicalization (47b), clefting (47c), pseudo-cleating (47d), nor can it served as an answer fragment (47e).

One argument is that [NP AP small] clauses cannot occur in the subject position without modification, as shown by the ungrammatically of (48).

A second argument is coordination tests make incorrect predictions about constituency, particularly regarding small clauses.

[45] One school of thought argues that this example has [the water up] behaving as a constituent small clause, while another school of thought argues that the verb "sponge" does not select for a small clause, and that the water up semantically, but not syntactically, shows the resultative state of the verb.

[45] Complement small clauses are related to the phenomena of raising-to-object, therefore this theory will be discussed in more detail for English and Korean.

[46] This is evident by the grammaticality of (i) and ungrammaticality of (ii) without raising-to-object behaviour as demonstrated in the table below: The range of scope can also implicate the subject of Raising in small clauses.

The phrase her an immature brat cannot be split up in example (d), which provides further evidence that the small clause behaves as a single unit.

However, the semantic difference between Mandarin Chinese and English with regards to its small clauses are represented by example (b) and (c).

This is evidence that there are more restrictive constraints on what is considered a small clause in Mandarin Chinese, which requires further research.

Here, the possessive verb yǒu takes a small clause complement in order to make a degree comparison between the subject and indirect object.

Dependent small clauses are similar to English in that they consist of an NP XP in a predicative relation.

Like many other Romance languages, Brazilian Portuguese has free subject-predicate inversion, although it is restricted here to verbs with single arguments.

[61] Additionally, first person pronouns, kinship terms, proper names, and other nouns with a vocative use are able to appear in NP1 position—except for the intermediate demonstrative so (the/that) which is not permitted in ESCs.

[61] Because English is agreement-prominent, there is inflexible SC word order and a heavy importance on intonational focus.

[60] These examples show the non-felicitous construction but they would be accepted by speakers if the underlined constituents are given emphatic stress and precede a long pause.