Sundial

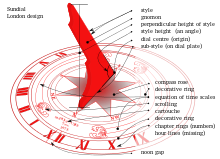

As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day.

It is common for inexpensive, mass-produced decorative sundials to have incorrectly aligned gnomons, shadow lengths, and hour-lines, which cannot be adjusted to tell correct time.

To obtain the national clock time, three corrections are required: The principles of sundials are understood most easily from the Sun's apparent motion.

The hour-lines will be spaced uniformly if the surface receiving the shadow is either perpendicular (as in the equatorial sundial) or circular about the gnomon (as in the armillary sphere).

The corresponding light-spot or shadow-tip, if it falls onto a flat surface, will trace out a conic section, such as a hyperbola, ellipse or (at the North or South Poles) a circle.

By 240 BC, Eratosthenes had estimated the circumference of the world using an obelisk and a water well and a few centuries later, Ptolemy had charted the latitude of cities using the angle of the sun.

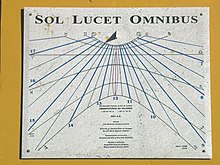

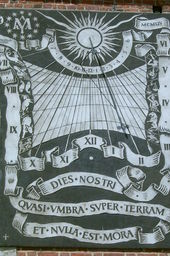

The motto is usually in the form of an epigram: sometimes sombre reflections on the passing of time and the brevity of life, but equally often humorous witticisms of the dial maker.

In other cases, the hour lines may be curved, or the equatorial bow may be shaped like a vase, which exploits the changing altitude of the sun over the year to effect the proper offset in time.

The Sunquest sundial, designed by Richard L. Schmoyer in the 1950s, uses an analemmic-inspired gnomon to cast a shaft of light onto an equatorial time-scale crescent.

[20] The most commonly observed sundials are those in which the shadow-casting style is fixed in position and aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, being oriented with true north and south, and making an angle with the horizontal equal to the geographical latitude.

If the shadow falls on a surface that is symmetrical about the celestial axis (as in an armillary sphere, or an equatorial dial), the surface-shadow likewise moves uniformly; the hour-lines on the sundial are equally spaced.

There is an alternative, simple method of finding the positions of the hour-lines which can be used for many types of sundial, and saves a lot of work in cases where the calculations are complex.

[citation needed] Since the hour angles are not evenly spaced, the equation of time corrections cannot be made via rotating the dial plate about the gnomon axis.

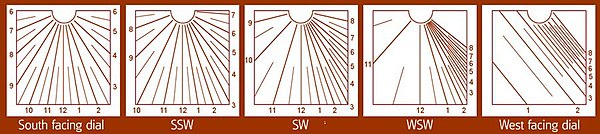

If the face of the vertical dial points directly south, the angle of the hour-lines is instead described by the formula:[30] where L is the sundial's geographical latitude,

Vertical dials that face north are uncommon, because they tell time only during the spring and summer, and do not show the midday hours except in tropical latitudes (and even there, only around midsummer).

If the style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, a spherical shape is convenient since the hour-lines are equally spaced, as they are on the equatorial dial shown here; the sundial is equiangular.

This pattern, built a couple of meters wide out of temperature-invariant steel invar, was used to keep the trains running on time in France before World War I.

[47] This collection of sundials and other astronomical instruments was built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then-new capital of Jaipur, India between 1727 and 1733.

The larger equatorial bow is called the Samrat Yantra (The Supreme Instrument); standing at 27 meters, its shadow moves visibly at 1 mm per second, or roughly a hand's breadth (6 cm) every minute.

The gnomon of a Foster-Lambert dial is neither vertical nor aligned with the Earth's rotational axis; rather, it is tilted northwards by an angle α = 45° - (Φ/2), where Φ is the geographical latitude.

In one simple version,[62] the front and back of the plate each have three columns, corresponding to pairs of months with roughly the same solar declination (June:July, May:August, April:September, March:October, February:November, and January:December).

[58] A peg gnomon is inserted at the top in the appropriate hole or face for the season of the year, and turned to the Sun so that the shadow falls directly down the scale.

Most commonly, the receiving surface is a geometrical plane, so that the path of the shadow-tip or light-spot (called declination line) traces out a conic section such as a hyperbola or an ellipse.

The collection of hyperbolae was called a pelekonon (axe) by the Greeks, because it resembles a double-bladed ax, narrow in the center (near the noonline) and flaring out at the ends (early morning and late evening hours).

The oldest example is perhaps the antiborean sundial (antiboreum), a spherical nodus-based sundial that faces true north; a ray of sunlight enters from the south through a small hole located at the sphere's pole and falls on the hour and date lines inscribed within the sphere, which resemble lines of longitude and latitude, respectively, on a globe.

With a knot or bead on the string as a nodus, and the correct markings, a diptych (really any sundial large enough) can keep a calendar well-enough to plant crops.

[77] Similar to sundials with a fixed axial style, a globe dial determines the time from the Sun's azimuthal angle in its apparent rotation about the earth.

[78] In centuries past, such dials were used to set mechanical clocks, which were sometimes so inaccurate as to lose or gain significant time in a single day.

[79] Such marks indicate local noon, and provide a simple and accurate time reference for households to set their clocks.

They typically consist of a horizontal sundial, which has in addition to a gnomon a suitably mounted lens, set to focus the rays of the sun at exactly noon on the firing pan of a miniature cannon loaded with gunpowder (but no ball).