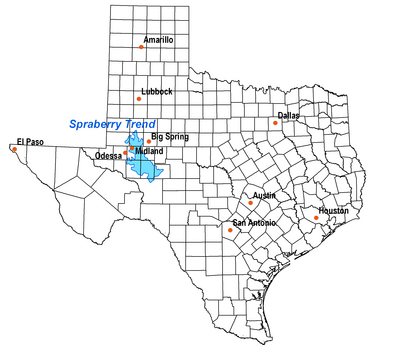

Spraberry Trend

After about three years of enthusiastic drilling, during which most of the initially promising wells showed precipitous and mysterious production declines, the area was dubbed "the world's largest unrecoverable oil reserve.

[3][4] The Spraberry Trend covers a large area – around 2,500 square miles (6,500 km2) – and includes portions of two Texas geographical regions, the Llano Estacado and the Edwards Plateau.

Elevations are generally between 2,500 and 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level, and the terrain varies from flat to rolling, with occasional canyons, known locally as "draws", cutting through the plateau.

That changed in 1949, when the same company drilled well Lee 2-D, which produced 319 barrels per day (50.7 m3/d) – hardly a spectacular discovery, but enough to pique the interest of numerous independent operators looking for opportunity around Midland.

In 1950, the cost of drilling and putting down 8,000 feet (2,400 m) of steel casing required a well to produce 50,000 barrels (7,900 m3) just to break even in the face of the low federally mandated price of $2.58/barrel.

Local companies that had been skeptical of the Spraberry since the beginning of the boom did not suffer the losses of the outsiders who had come in expecting to profit in the huge oil play.

[13] In the following years, each operator developed its own methods of dealing with the unusual reservoir, and began to employ a technique known as "hydrofracturing" – forcing water down wells at extreme pressure, causing the rocks to fracture further, resulting in increased oil flow.

[15] During the initial boom period the Spraberry promoters carried out an aggressive campaign to bring in outside investment, making exorbitant claims of the potential easy profit with the vast reserves of oil.

[16] Using the normal 40-acre (160,000 m2) spacing employed elsewhere in West Texas proved impossible on the Spraberry; wells that close competed against each other, as yields per-acre from the difficult reservoir were dropping into the hundreds of barrels rather than the expected thousands.

After a series of lawsuits and court battles, the Railroad Commission backed down, compromising with the operators by allowing them a set number of days per month during which they could pump oil and flare gas.