Structural geology

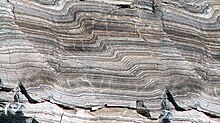

Structural geology is the study of the three-dimensional distribution of rock units with respect to their deformational histories.

The primary goal of structural geology is to use measurements of present-day rock geometries to uncover information about the history of deformation (strain) in the rocks, and ultimately, to understand the stress field that resulted in the observed strain and geometries.

This understanding of the dynamics of the stress field can be linked to important events in the geologic past; a common goal is to understand the structural evolution of a particular area with respect to regionally widespread patterns of rock deformation (e.g., mountain building, rifting) due to plate tectonics.

[1] Folded and faulted rock strata commonly form traps that accumulate and concentrate fluids such as petroleum and natural gas.

Veins of minerals containing various metals commonly occupy faults and fractures in structurally complex areas.

These structurally fractured and faulted zones often occur in association with intrusive igneous rocks.

Deposits of gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, and other metals, are commonly located in structurally complex areas.

Structural fabrics and defects such as faults, folds, foliations and joints are internal weaknesses of rocks which may affect the stability of human engineered structures such as dams, road cuts, open pit mines and underground mines or road tunnels.

[2] In addition, areas of karst landscapes which reside atop caverns, potential sinkholes, or other collapse features are of particular importance for these scientists.

For instance, a hydrogeologist may need to determine if seepage of toxic substances from waste dumps is occurring in a residential area or if salty water is seeping into an aquifer.

The orientation of the lineation can then be calculated from the rake and strike-dip information of the plane it was measured from, using a stereographic projection.

Generally it is easier to record strike and dip information of planar structures in dip/dip direction format as this will match all the other structural information you may be recording about folds, lineations, etc., although there is an advantage to using different formats that discriminate between planar and linear data.

Planar structures are named according to their order of formation, with original sedimentary layering the lowest at S0.

This may be possible by observing porphyroblast formation in cleavages of known deformation age, by identifying metamorphic mineral assemblages created by different events, or via geochronology.

For convenience some geologists prefer to annotate them with a subscript S, for example Ls1 to differentiate them from intersection lineations, though this is generally redundant.

Stereographic projection is a method for analyzing the nature and orientation of deformation stresses, lithological units and penetrative fabrics wherein linear and planar features (structural strike and dip readings, typically taken using a compass clinometer) passing through an imagined sphere are plotted on a two-dimensional grid projection, facilitating more holistic analysis of a set of measurements.

This branch of structural geology deals mainly with the orientation, deformation and relationships of stratigraphy (bedding), which may have been faulted, folded or given a foliation by some tectonic event.

This is mainly a geometric science, from which cross sections and three-dimensional block models of rocks, regions, terranes and parts of the Earth's crust can be generated.

Study of regional structure is important in understanding orogeny, plate tectonics and more specifically in the oil, gas and mineral exploration industries as structures such as faults, folds and unconformities are primary controls on ore mineralisation and oil traps.

Without modeling or interpretation of the subsurface, geologists are limited to their knowledge of the surface geological mapping.

If only reliant on the surface geology, major economic potential could be missed by overlooking the structural and tectonic history of the area.

The mechanical properties of rock play a vital role in the structures that form during deformation deep below the earth's crust.

The conditions in which a rock is present will result in different structures that geologists observe above ground in the field.

At the conditions under the earth's crust of extreme high temperature and pressure, rocks are ductile.

Other vital conditions that contribute to the formation of structure of rock under the earth are the stress and strain fields.

Reversible, linear, elasticity involves the stretching, compressing, or distortion of atomic bonds.

Stress has caused permanent change of shape in the material by involving the breaking of bonds.

The area under the elastic portion of the stress-strain curve is the strain energy absorbed per unit volume.