Sudetenland

When Czechoslovakia was reconstituted after World War II, the Sudeten Germans were expelled and the region today is inhabited almost exclusively by Czech speakers.

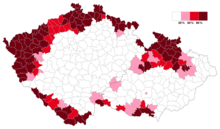

Parts of the now-Czech regions of Karlovy Vary, Liberec, Olomouc, Moravia-Silesia, South Moravia and Ústí nad Labem are within the former Sudetenland.

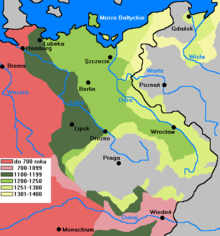

In the Middle Ages the regions situated on the mountainous border of the Duchy and the Kingdom of Bohemia (Crown of Saint Václav) had since the Migration Period been settled mainly by western Slavic Czechs.

After the extinction of the Přemyslid dynasty in 1306, the Bohemian nobility backed John of Luxembourg as king against his rival Duke Henry of Carinthia.

From the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt that collapsed at the 1620 Battle of White Mountain, the Habsburgs gradually integrated the Kingdom of Bohemia into their monarchy.

From 1627, the Habsburgs enforced the so-called Verneuerte Landesordnung ("Renewed Land's Constitution"), and one of its consequences was that German, according to mother tongue, gradually became the primary and official language, while Czech declined to a secondary role in the Empire.

Emperor Joseph II in 1780 renounced the coronation ceremony as Bohemian king and unsuccessfully tried to push German through as sole official language in all Habsburg lands (including Hungary).

Contrastingly, in the course of the Romanticism movement national tensions arose, both in the form of the Austroslavism ideology developed by Czech politicians like František Palacký and Pan-Germanist activist raising the German question.

The German deputies of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia in the Imperial Council (Reichsrat) referred to the Fourteen Points of US President Woodrow Wilson and the right proposed therein to self-determination and attempted to negotiate the union of the German-speaking territories with the new Republic of German Austria, which itself aimed at joining Weimar Germany.

Coolidge insisted on respecting the Germans' right to self-determination and uniting all German-speaking areas with either Germany or Austria, with the exception of northern Bohemia.

Allen Dulles was the American's chief diplomat in the Czechoslovak Commission and emphasized preserving the unity of the Czech lands.

[3] Four regional governmental units were established: The U.S. commission to the Paris Peace Conference issued a declaration, which gave unanimous support for "unity of Czech lands".

According to Elizabeth Wiskemann, despite the initial resistance to the Czechoslovak rule, the Sudeten German population was not entirely opposed to annexation by Czechoslovakia.

Sudeten economy and industry relied on the rest of Bohemia, and local industrialists were afraid of "Reich German competition and therefore of the talk of handing them over".

The glass-making sector was affected by decreased spending power and by protective measures in other countries, and many German workers lost their work.

[7] The high unemployment, as well as the imposition of Czech in schools and all public spaces, made people more open to populist and extremist movements such as fascism, communism and German irredentism.

On 24 April 1938, the SdP proclaimed the Karlsbader Programm, which demanded in eight points the complete equality between the Sudeten Germans and the Czech people.

[clarification needed][8] In August, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain sent Lord Runciman on a mission to Czechoslovakia to see if he could obtain a settlement between the Czechoslovak government and the Germans in the Sudetenland.

[9] A full account of his report, including summaries of the conclusions of his meetings with the various parties, which he made in person to the Cabinet on his return to the United Kingdom, is found in the Document CC 39(38).

Halifax said that the transfer of these areas to Germany would almost certainly be a good thing adding that the Czechoslovak army would certainly oppose that very strongly and that Beneš had said that it would fight, rather than accept it.

[12] British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden on 15 September and agreed to the cession of the Sudetenland.

Hitler, aiming to use the crisis as a pretext for war, now demanded not only the annexation of the Sudetenland but also the immediate military occupation of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia, thus giving the Czechoslovak army no time to adapt its defence measures to the new borders.

The Czech part of Czechoslovakia was subsequently invaded by Germany in March 1939, with a portion being annexed and the remainder turned into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

(The Ruthenian part, Subcarpathian Rus, made also an attempt to declare its sovereignty as Carpatho-Ukraine but only with ephemeral success since the area was soon annexed by Hungary.)

[15] Contemporary reports of The Times found that there was a "large number of Sudetenlanders who actively opposed annexation", and that the pro-German policy was challenged by the moderates within the SdP as well; according to Wickham Steed, over 50% of Henlein's supporters favoured greater autonomy within Czechoslovakia rather than joining Germany.

[16] Sudeten German historian Emil Franzel [de] argues that the mainstream wing of Henlein's party was "not striving for annexation to Germany, but for genuine autonomy", and the majority of negotiators who conducted talks with Hodža and Beneš belonged to the pro-autonomy wing and were unaware of Henlein's agreements with Hitler.

On 14 April 1939, the annexed territories were divided, with the southern parts being incorporated into the neighbouring Reichsgaue of Niederdonau, Oberdonau and Bayerische Ostmark.

The northern and the western parts were reorganised as the Reichsgau Sudetenland, with the city of Reichenberg (present-day Liberec) established as its capital.

The remaining Germans, who were proven antifascists and skilled laborers, were allowed to stay in Czechoslovakia but were later forcefully dispersed within the country.