Sumer

Sumer (/ˈsuːmər/) is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC.

Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, a surplus which enabled them to form urban settlements.

[2][3] The Akkadians, the East Semitic-speaking people who later conquered the Sumerian city-states, gave Sumer its main historical name, but the phonological development of the term šumerû is uncertain.

[33][34] The status of Dilmun as the Sumerians’ ancestral homeland has not been established, but archaeologists have found evidence of civilization in Bahrain, namely the existence of Mesopotamian-style round disks.

[41] Juris Zarins believes the Sumerians lived along the coast of Eastern Arabia, today's Persian Gulf region, before it was flooded at the end of the Ice Age.

An incomplete list of cities that may have been visited, interacted and traded with, invaded, conquered, destroyed, occupied, colonized by and/or otherwise within the Sumerians’ sphere of influence (ordered from south to north): Apart from Mari, which lies full 330 kilometres (205 miles) north-west of Agade, but which is credited in the king list as having exercised kingship in the Early Dynastic II period, and Nagar, an outpost, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad in what are now the Bābil, Diyala, Wāsit, Dhi Qar, Basra, Al-Muthannā and Al-Qādisiyyah governorates of Iraq.

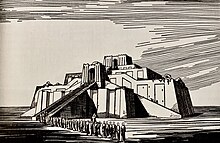

[50][51] By the time of the Uruk period, c. 4100–2900 BC calibrated, the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified, temple-centered cities, with populations of over 10,000 people, where centralized administrations employed specialized workers.

Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area—from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as western Iran.

[52]: 2–3 The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists, like that found at Tell Brak, had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures.

[52][page needed] Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and were most likely headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women.

Later, Lugal-zage-si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.

Thorkild Jacobsen has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre- and post-Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a "Semitic vs. Sumerian" conflict.

Later, the Third Dynasty of Ur under Ur-Nammu and Shulgi (c. 2112–2004 BC, middle chronology), whose power extended as far as southern Assyria, has been erroneously called a "Sumerian renaissance" in the past.

The independent Amorite states of the 20th to 18th centuries are summarized as the "Dynasty of Isin" in the Sumerian king list, ending with the rise of Babylonia under Hammurabi c. 1800 BC.

[64] However, the archaeological record shows clear uninterrupted cultural continuity from the time of the early Ubaid period (5300–4700 BC C-14) settlements in southern Mesopotamia.

According to this theory, farming peoples spread down into southern Mesopotamia because they had developed a temple-centered social organization for mobilizing labor and technology for water control, enabling them to survive and prosper in a difficult environment.

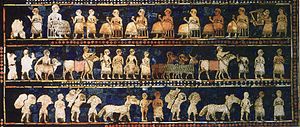

Beneath the lu-gal ("great man" or king), all members of society belonged to one of two basic strata: The "lu" or free person, and the slave (male, arad; female geme).

[67][68] Inscriptions describing the reforms of king Urukagina of Lagash (c. 2350 BC) say that he abolished the former custom of polyandry in his country, prescribing that a woman who took multiple husbands be stoned with rocks upon which her crime had been written.

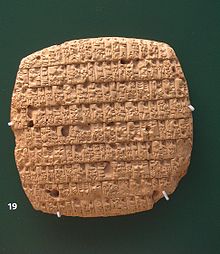

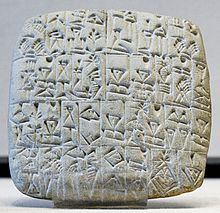

A large body of hundreds of thousands of texts in the Sumerian language have survived, including personal and business letters, receipts, lexical lists, laws, hymns, prayers, stories, and daily records.

The first saw creation as the result of a series of hieroi gamoi or sacred marriages, involving the reconciliation of opposites, postulated as a coming together of male and female divine beings, the gods.

Another important Sumerian hieros gamos was that between Ki, here known as Ninhursag or "Lady of the Mountains", and Enki of Eridu, the god of fresh water which brought forth greenery and pasture.

At an early stage, following the dawn of recorded history, Nippur, in central Mesopotamia, replaced Eridu in the south as the primary temple city, whose priests exercised political hegemony on the other city-states.

Sumerian artefacts show great detail and ornamentation, with fine semi-precious stones imported from other lands, such as lapis lazuli, marble, and diorite, and precious metals like hammered gold, incorporated into the design.

[96] Discoveries of obsidian from far-away locations in Anatolia and lapis lazuli from Badakhshan in northeastern Afghanistan, beads from Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and several seals inscribed with the Indus Valley script suggest a remarkably wide-ranging network of ancient trade centered on the Persian Gulf.

[100] Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Turbinella pyrum and Pleuroploca trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500–2000 BC.

[107][108][109][110][111][112] Gudea, the ruler of the Neo-Summerian Empire at Lagash, is recorded as having imported "translucent carnelian" from Meluhha, generally thought to be the Indus Valley area.

[114] Rural loans commonly arose as a result of unpaid obligations due to an institution (such as a temple), in this case the arrears were considered to be lent to the debtor.

Examples of Sumerian technology include: the wheel, cuneiform script, arithmetic and geometry, irrigation systems, Sumerian boats, lunisolar calendar, bronze, leather, saws, chisels, hammers, braces, bits, nails, pins, rings, hoes, axes, knives, lancepoints, arrowheads, swords, glue, daggers, waterskins, bags, harnesses, armor, quivers, war chariots, scabbards, boots, sandals, harpoons and beer.

The Sumerians had three main types of boats: Evidence of wheeled vehicles appeared in the mid-4th millennium BC, near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture) and Central Europe.

Several centuries after the invention of cuneiform, the use of writing expanded beyond debt/payment certificates and inventory lists to be applied for the first time, about 2600 BC, to messages and mail delivery, history, legend, mathematics, astronomical records, and other pursuits.