Surface reconstruction

If a surface is introduced to the surroundings by terminating the crystal along a given plane, then these forces are altered, changing the equilibrium positions of the remaining atoms.

This makes intuitive sense, as a surface layer that experiences no forces from the open region can be expected to contract towards the bulk.

The general symmetry of a layer might also change, as in the case of the Pt (100) surface, which reconstructs from a cubic to a hexagonal structure.

These reconstructions can assume a variety of forms when the detailed interactions between different types of atoms are taken into account, but some general principles can be identified.

The reconstruction of a surface with adsorption will depend on the following factors: Composition plays an important role in that it determines the form that the adsorption process takes, whether by relatively weak physisorption through van der Waals interactions or stronger chemisorption through the formation of chemical bonds between the substrate and adsorbate atoms.

[3] In general, the change in a surface layer's structure due to a reconstruction can be completely specified by a matrix notation proposed by Park and Madden.

This notation is often used to describe reconstructions concisely, but does not directly indicate changes in the layer symmetry (for example, square to hexagonal).

Special techniques are thus required to measure the positions of the surface atoms, and these generally fall into two categories: diffraction-based methods adapted for surface science, such as low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) or Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy, and atomic-scale probe techniques such as scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) or atomic force microscopy.

Of these, STM has been most commonly used in recent history due to its very high resolution and ability to resolve aperiodic features.

A very well known example of surface reconstruction occurs in silicon, a semiconductor commonly used in a variety of computing and microelectronics applications.

With a diamond-like face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice, it exhibits several different well-ordered reconstructions depending on temperature and on which crystal face is exposed.

The observed reconstruction is a 2×1 periodicity, explained by the formation of dimers, which consist of paired surface atoms, decreasing the number of dangling bonds by a factor of two.

This structure was gradually inferred from LEED and RHEED measurements and calculation, and was finally resolved in real space by Gerd Binnig, Heinrich Rohrer, Ch.

Gerber and E. Weibel as a demonstration of the STM, which was developed by Binnig and Rohrer at IBM's Zurich Research Laboratory.

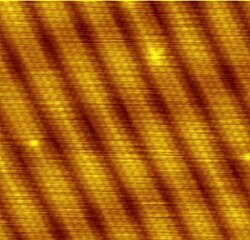

In the bulk gold is an (fcc) metal, with a surface structure reconstructed into a distorted hexagonal phase.

Molecular-dynamics simulations indicate that this rotation occurs to partly relieve a compressive strain developed in the formation of this hexagonal reconstruction, which is nevertheless favored thermodynamically over the unreconstructed structure.

This results in a recovery of the square (1×1) structure within the disordered phase and makes sense as at high temperatures the energy reduction allowed by the hexagonal reconstruction can be presumed to be less significant.