Taiwanese Hokkien

[24] From that period onwards, many people from the Hokkien-speaking regions (southern Fujian) started to emigrate overseas due to political and economic reasons.

Zheng and a Chinese official suggested sending victims to Taiwan and provide "for each person three taels of silver and for each three people one ox".

In the 1661 Siege of Fort Zeelandia, Chinese general Koxinga, marshaling a military force composed of fellow hometown hoklo soldiers of Southern Fujian, expelled the Dutch and established the Kingdom of Tungning.

In 1683, Chinese admiral Shi Lang, marshaling a military force again composed of fellow hometown hoklo soldiers of Southern Fujian, attacked Taiwan in the Battle of Penghu, ending the Tungning era and beginning Qing dynasty rule (until 1895).

(郡中鴃舌鳥語,全不可曉。如:劉呼「澇」、陳呼「澹」、莊呼「曾」、張呼「丟」。余與吳待御兩姓,吳呼作「襖」,黃則無音,厄影切,更為難省。)The tone of Huang's message foretold the uneasy relationships between different language communities and colonial establishments over the next few centuries.

In the early 20th century, the Hoklo people in Taiwan could be categorized as originating from modern-day Xiamen, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Zhangpu.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, due to military defeat to the Japanese, the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan to Japan, causing contact with the Hokkien-speaking regions of mainland China to stop.

The Second Sino-Japanese War beginning in 1937 brought stricter measures into force, and along with the outlawing of romanized Taiwanese, various publications were prohibited and Confucian-style private schools which taught Classical Chinese with literary Southern Min pronunciation – was closed down in 1939.

[39] Only after the lifting of martial law in 1987 and the mother tongue movement in the 1990s did Taiwan finally see a true revival in Taiwanese Hokkien.

Others prefer the names Southern Min, Minnan or Hokkien as this views Taiwanese as a form of the Chinese variety spoken in Fujian province in mainland China.

[citation needed] In the American Community Survey run by the United States Census Bureau, Taiwanese was referred to as "Formosan" from 2012 to 2015 and as "Min Nan Chinese" since 2016.

Although uncommon in written Taiwanese, there is a ninth tone which is used for three main purposes: contractions, triplicated adjectives, and loan words.

Modern linguistic studies (by Robert L. Cheng and Chin-An Li, for example) estimate that most (75% to 90%) Taiwanese words have cognates in other Sinitic languages.

Often the former group lacks a standard Han character, and the words are variously considered colloquial, intimate, vulgar, uncultured, or more concrete in meaning than the pan-Chinese synonym.

Unlike the English Germanic/Latin contrast, however, the two groups of Taiwanese words cannot be as strongly attributed to the influences of two disparate linguistic sources.

For example, the Han characters of the vulgar slang 'khoàⁿ sáⁿ-siâu' (看三小, substituted for the etymologically correct 看啥潲, meaning 'What the hell are you looking at?')

The additional necessities are the nasal symbol ⟨ⁿ⟩ (superscript ⟨n⟩; the uppercase form ⟨N⟩ is sometimes used in all caps texts,[58] such as book titles or section headings), and the tonal diacritics.

In 2006, the National Languages Committee (Ministry of Education, Republic of China) proposed its Taiwanese Romanization System (Tâi-ôan Lô-má-jī pheng-im, Tâi-Lô).

There are also a number of other pronunciation and lexical differences between the Taiwanese variants; the online Ministry of Education dictionary specifies these to a resolution of eight regions on Taiwan proper, in addition to Kinmen and Penghu.

Thus, some scholars (i.e., Klöter, following 董忠司) have divided Taiwanese into five subdialects, based on geographic region:[67] Both phian-hái and phian-lāi are intermediate dialects between hái-kháu and lāi-po͘, these also known as thong-hêng (通行腔) or "不泉不漳".

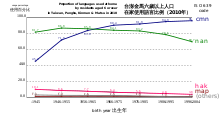

[citation needed] A great majority of people in Taiwan can speak both Mandarin and Hokkien, but the degree of fluency varies widely.

[34] There are, however, small but significant numbers of people in Taiwan, mainly but not exclusively Hakka and Mainlanders, who cannot speak Taiwanese fluently.

In the broadcast media where Mandarin is used in many genres, soap opera, variety shows, and even some news programs can also be found in Taiwanese.

The resulting work containing the Old and the New Testaments, in the Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography, was completed in 1930 and published in 1933 as the Amoy Romanized Bible [nan] (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sin-kū-iok ê Sèng-keng).

[70] The Ko–Tân (Kerygma) Colloquial Taiwanese Version of the New Testament (Sin-iok) in Pe̍h-ōe-jī, also known as the Red Cover Bible [nan] (Âng-phoê Sèng-keng), was published in 1973 as an ecumenical effort between the Protestant Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Roman Catholic mission Maryknoll.

This translation used a more modern vocabulary (somewhat influenced by Mandarin), and reflected the central Taiwan dialect, as the Maryknoll mission was based near Tâi-tiong.

James Soong restricted the use of Taiwanese Hokkien and other local tongues in broadcasting while serving as Director of the Government Information Office earlier in his career, but later became one of the first politicians of Mainlander origin to use it in semi-formal occasions.

[78] Former President Ma Ying-jeou spoke in Taiwanese during his 2008 Double Ten Day speech when he was talking about the state of the economy in Taiwan.

[79][80] In 2002, the Taiwan Solidarity Union, a party with about 10% of the Legislative Yuan seats at the time, suggested making Taiwanese Hokkien a second official language.

[84][failed verification][dubious – discuss] Since the 2000s, elementary school students are required to take a class in either Taiwanese, Hakka or aboriginal languages.