Tang dynasty

Despite early victories scored by the Tang general Guo Ziyi (697–781), the newly recruited troops of the army at the capital were no match for An Lushan's frontier veterans; the court fled Chang'an.

[72] However, Xianzong's successors proved less capable and more interested in the leisure of hunting, feasting, and playing outdoor sports, allowing eunuchs to amass more power as drafted scholar-officials caused strife in the bureaucracy with factional parties.

[76] In addition to factors like natural calamity and jiedushi claiming autonomy, a rebellion by Huang Chao (874–884) devastated both northern and southern China, took an entire decade to suppress, resulted in the sacking of both Chang'an and Luoyang.

[81][82] During the last two decades of the Tang dynasty, the gradual collapse of central authority led to the rise of the rival military figures Li Keyong and Zhu Wen in northern China.

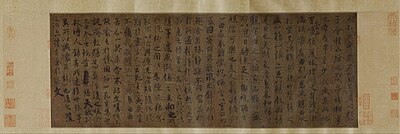

[9] Although the central and local governments kept an enormous number of records about land property in order to assess taxes, it became common practice in the Tang for literate and affluent people to create their own private documents and signed contracts.

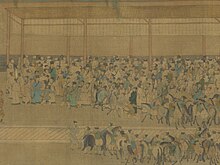

When the Chinese prefectural government officials travelled to the capital in 643 to give the annual report of the affairs in their districts, Emperor Taizong discovered that many had no proper quarters to rest in and were renting rooms with merchants.

The Tang law code ensured equal division of inherited property among legitimate heirs, encouraging social mobility by preventing powerful families from becoming landed nobility through primogeniture.

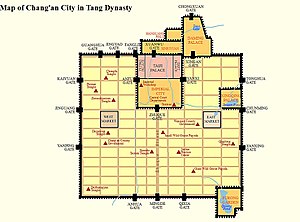

Near the beginning of his reign in 713, he liquidated the Inexhaustible Treasury of a prominent Buddhist monastery in Chang'an which had collected vast riches as multitudes of anonymous repentants left money, silk, and treasure at its doors.

[113] The Chinese population would not dramatically increase until the Song dynasty, when it doubled to 100 million because of extensive rice cultivation in central and southern China, coupled with higher yields of grain sold in a growing market.

[183] Although the Silk Road from China to Europe and the Western world was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu (141–87 BC) during the Han, it was reopened by the Tang in 639, when Hou Junji (d. 643) conquered the West, and remained open for almost four decades.

[191] During the Tang dynasty, thousands of foreign expatriate merchants came and lived in numerous Chinese cities to do business with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Bengalis, Sinhalese, Khmers, Chams, Jews and Nestorian Christians of the Near East.

[209][210] From this time period, the Arab merchant Shulama once wrote of his admiration for Chinese seafaring junks, but noted that their draft was too deep for them to enter the Euphrates River, which forced them to ferry passengers and cargo in small boats.

An artificial lake used as a transshipment pool was dredged east of Chang'an in 743, where curious northerners could finally see the array of boats found in southern China, delivering tax and tribute items to the imperial court.

[231][232] Timothy C. Wong places this story within the wider context of Tang love tales, which often share the plot designs of quick passion, inescapable societal pressure leading to the abandonment of romance, followed by a period of melancholy.

[233] Wong states that this scheme lacks the undying vows and total self-commitment to love found in Western romances such as Romeo and Juliet, but that underlying traditional Chinese values of indivisibility of self from one's environment, including from society) served to create the necessary fictional device of romantic tension.

Other important literature included Duan Chengshi's (d. 863) Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang, an entertaining collection of foreign legends and hearsay, reports on natural phenomena, short anecdotes, mythical and mundane tales, as well as notes on various subjects.

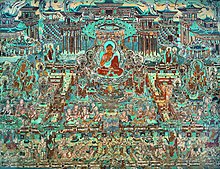

[240] Buddhism, originating in India around the time of Confucius, continued its influence during the Tang period and was accepted by some members of imperial family, becoming thoroughly sinicised and a permanent part of Chinese traditional culture.

Buddhist monasteries played an integral role in Chinese society, offering lodging for travellers in remote areas, schools for children throughout the country, and a place for urban literati to stage social events and gatherings such as going-away parties.

[268] While renowned for their politeness, courtesans were reputed to dominate conversations among elite men, and as being unafraid to openly criticise the rudeness of prominent male guests, including for talking too much, too loudly, or for boasting of their accomplishments.

[273] The preferred hairstyle for women was to bunch their hair up like "an elaborate edifice above the forehead",[274] while affluent ladies wore extravagant head ornaments, combs, pearl necklaces, face powders, and perfumes.

[286] During the Tang, the many common foodstuffs and cooking ingredients in addition to those already listed were barley, garlic, salt, turnips, soybeans, pears, apricots, peaches, apples, pomegranates, jujubes, rhubarb, hazelnuts, pine nuts, chestnuts, walnuts, yams, taro, etc.

[288] From the trade overseas and over land, the Chinese acquired peaches from Samarkand, date palms, pistachios, and figs from Persia, pine nuts and ginseng roots from Korea and mangoes from Southeast Asia.

Yi Xing's astronomical clock and water-powered armillary sphere became well known throughout the country, since students attempting to pass the imperial examinations by 730 had to write an essay on the device as an exam requirement.

[300] Furthermore, as the historian Charles Benn describes it: Midway up the southern side of the mountain was a dragon ... the beast opened its mouth and spit brew into a goblet seated on a large [iron] lotus leaf beneath.

If he was slow in draining the cup and returning it to the leaf, the door of a pavilion at the top of the mountain opened and a mechanical wine server, dressed in a cap and gown, emerged with a wooden bat in his hand.

[301] There are many stories of automatons used in the Tang, including general Yang Wulian's wooden statue of a monk who stretched his hands out to collect contributions; when the number of coins reached a certain weight, the mechanical figure moved his arms to deposit them in a satchel.

[210][323] Since the time of the Han, the Chinese had drilled deep boreholes to transport natural gas from bamboo pipelines to stoves where cast iron evaporation pans boiled brine to extract salt.

[324] During the Tang dynasty, a gazetteer of Sichuan province stated that at one of these 182 m (597 ft) 'fire wells', men collected natural gas into portable bamboo tubes which could be carried around for dozens of kilometres and still produce a flame.

[326] In 747, Emperor Xuanzong had a "Cool Hall" built in the imperial palace, which Tang Yulin described as having water-powered fan wheels for air conditioning as well as rising jet streams of water from fountains.

The Tang period was placed into the enormous 294-volume universal history text of the Zizhi Tongjian, edited, compiled, and completed in 1084 by a team of scholars under the Song dynasty Chancellor Sima Guang.