Tasman Bridge disaster

Twelve people were killed, including seven crew on board Lake Illawarra, and the five occupants of four cars which fell 45 metres (150 ft) after driving off the bridge.

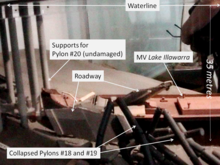

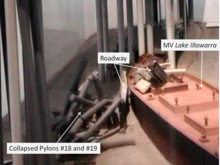

Lake Illawarra listed to starboard and sank within minutes a short distance to the south, in 35 metres (115 ft) of water.

The subsequent Court of Marine Inquiry found that Pelc had not handled the ship in a proper and seamanlike manner, and his certificate was suspended for six months.

Two drivers managed to stop their vehicles at the edge, but not before their front wheels had dropped over the lip of the bridge deck.

Ling then noticed several cars ahead of him seemingly disappear as they drove straight over the edge, so he slammed his foot on the brakes.

At 2:30 am, a fourteen-man Navy Clearance Diving Team flew to Hobart to assist water police in the recovery of the vehicles which had driven off the bridge.

The divers operated in hazardous conditions, with little visibility and strong river currents, contending with bridge debris such as shattered concrete, reinforced steel rods, railings, pipes, lights, wire and power cables.

Strong winds on the third day brought down debris from the bridge above, including power cables, endangering the divers working below.

The day after the incident, as 30,000 residents set out for work, they found that the former three-minute commute over the bridge had turned into a 90-minute trip.

"[13] A study of police data found that in the six months after the disaster, crime rose 41% on the eastern shore, while the rate on the city's western side fell.

Visible progress on restoration of the bridge was slow because of the need for extensive underwater surveys of debris and the time required for design of the rebuilding.

"[13] A sociological study described how the physical isolation led to debonding (the setting aside of bonds that constitute the fabric of normal social life).

The loss of the Tasman Bridge in Hobart disconnected two parts of the city and had far-reaching effects on the people separated.

[17] The disaster was a major contributor to ferry services being the lifeline for people needing to cross the river for daily work.

This survey took several months to complete, and parts of the bridge weighing up to 500 tonnes (550 short tons; 1,100,000 lb) were accurately located using equipment developed by the University of Tasmania and the Public Works Department.

[21] The engineering design of the Tasman Bridge provided impact absorbing fendering to the pile caps of the main navigation span capable of withstanding a glancing collision by a large ship, but all other piers were unprotected.

When river traffic "comprises large vessels, even at low speed, the consequences of pier failure can be catastrophic".

In 1987, a system of sensors measuring river currents, tidal height, and wind speed was installed near the bridge to provide data for ship movements in the area.

As an added precaution, it is now mandatory for most large vessels to have a tug in attendance as they transit the bridge in the event that assistance with steerage may be required.

The eastern shore eventually became a more self-contained community, with a higher level of employment and improved services and amenities, than had been the case prior to the disaster.

[26] A small service, led by members of the Tasmanian Council of Churches, was held on the occasion of the reopening on Saturday 8 October 1977.

In his address to the gathering, the Tasmanian Premier Jim Bacon stated that some people were still struggling with the memories of its effects, and he commended the resilience of the community in coping with the disaster.

The Governor at the time, Sir Guy Green, described the pain and loss of loved ones and the social and economic disruption.