Textual criticism of the New Testament

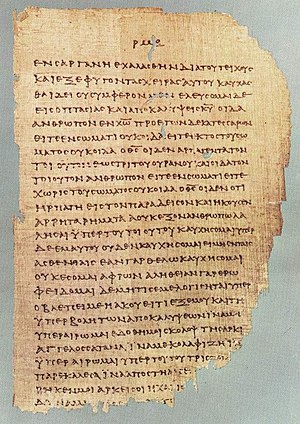

Its progress consists not in the growing perfection of an ideal in the future, but in approximation towards complete ascertainment of definite facts of the past, that is, towards recovering an exact copy of what was actually written on parchment or papyrus by the author of the book or his amanuensis.

[3]Historically, attempts have been made to sort new New Testament manuscripts into one of three or four theorized text-types (also styled unhyphenated: text types) or looser clusters.

However, the sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, chiefly in that it makes stemmatics in many cases impossible, because many copyists used two or more different manuscripts as sources.

[16] In 1734, Johann Albrecht Bengel was the first scholar to propose classifying manuscripts into text-types (such as 'African' or 'Asiatic'), and to attempt to systematically analyse which ones were superior and inferior.

[16] Johann Jakob Wettstein applied textual criticism to the Greek New Testament edition he published in 1751–2, and introduced a system of symbols for manuscripts.

[16] From 1774 to 1807, Johann Jakob Griesbach adapted Bengel's text groups and established three text-types (later known as 'Western', 'Alexandrian', and 'Byzantine'), and defined the basic principles of textual criticism.

[19][20] Karl Lachmann became the first scholar to publish a critical edition of the Greek New Testament (1831) that was not simply based on the Textus Receptus anymore, but sought to reconstruct the original biblical text following scientific principles.

[16] In the decades thereafter, important contributions were made by Constantin von Tischendorf, who discovered numerous manuscripts including the Codex Sinaiticus (1844), published several critical editions that he updated several times, culminating in the 8th: Editio Octava Critica Maior (11 volumes, 1864–1894).

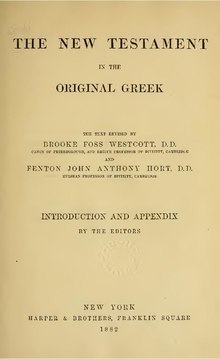

[16] Until the publication of the Introduction and Appendix of Westcott and Hort in 1882, scholarly opinion remained that the Alexandrian text was represented by the codices Vaticanus (B), Ephraemi Rescriptus (C), and Regius/Angelus (L).

[16] Puskas & Robbins (2012) noted that, despite significant advancements since 1881, the text of the NA27 differs much more from the Textus Receptus than from Westcott and Hort, stating that 'the contribution of these Cambridge scholars appears to be enduring.

A few textual critics, especially those in France, argue that the Western text-type, an old text from which the Vetus Latina or Old Latin versions of the New Testament are derived, is closer to the originals.

[citation needed] In the United States, some critics have a dissenting view that prefers the Byzantine text-type, such as Maurice A. Robinson and William Grover Pierpont.

This position is also held by Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont in their The New Testament in the Original Greek: Byzantine Textform, and the King James Only Movement.

The Neo-Byzantines (or new Byzantines) of the 16th and 17th centuries first formally compiled the New Testament Received Text under such textual analysts as Erasmus, Stephanus (Robert Estienne), Beza, and Elzevir.

A religiously conservative Protestant from Australia, his Neo-Byzantine School principles maintain that the representative or majority Byzantine text, such as compiled by Hodges & Farstad (1985) or Robinson & Pierpont (2005), is to be upheld unless there is a "clear and obvious" textual problem with it.

In modern translations of the Bible such as the New International Version, the results of textual criticism have led to certain verses, words and phrases being left out or marked as not original.

[33] Various groups of highly conservative Christians believe that when Ps.12:6–7 speaks of the preservation of the words of God, that this nullifies the need for textual criticism, lower, and higher.