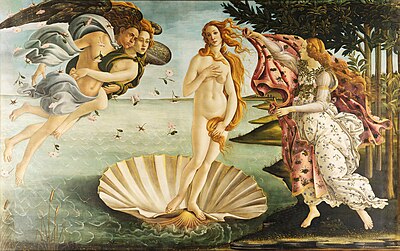

The Birth of Venus

While there are subtleties in the painting, its main meaning is a straightforward, if individual, treatment of a traditional scene from Greek mythology, and its appeal is sensory and very accessible, hence its enormous popularity.

[2] In the centre, the goddess Venus (newly born in fully grown state, in accordance with tradition) stands nude in a giant scallop shell.

[5] At the right a female figure who may be floating slightly above the ground holds out a rich cloak or dress to cover Venus when she reaches the shore, as she is about to do.

Canvas was increasing in popularity, perhaps especially for secular paintings for country villas, which were decorated more simply, cheaply and cheerfully than those for city palazzi, being designed for pleasure more than ostentatious entertainment.

Her shoulders, for example, instead of forming a sort of architrave to her torso, as in the antique nude, run down into her arms in the same unbroken stream of movement as her floating hair.

[17] Ignoring the size and positioning of the wings and limbs of the flying pair on the left, which bother some other critics, Kenneth Clark calls them: ...perhaps the most beautiful example of ecstatic movement in the whole of painting.

This was first suggested by Herbert Horne in his monograph of 1908, the first major modern work on Botticelli, and long followed by most writers, but more recently has been widely doubted, though it is still accepted by some.

This was the year after their father died at the age of 46, leaving the young boys wards of their cousin Lorenzo il Magnifico, of the senior branch of the Medici family and de facto ruler of Florence.

But in 1975 it emerged that, unlike the Primavera, the Birth is not in the inventory, apparently complete, made in 1499 of the works of art belonging to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco's branch of the family.

[26] Many art historians who specialize in the Italian Renaissance have found Neoplatonic interpretations, of which two different versions have been articulated by Edgar Wind and Ernst Gombrich,[27] to be the key to understanding the painting.

[29] A Neoplatonic reading of Botticelli's Birth of Venus suggests that 15th-century viewers would have looked at the painting and felt their minds lifted to the realm of divine love.

The composition, with a central nude figure, and one to the side with an arm raised above the head of the first, and winged beings in attendance, would have reminded its Renaissance viewers of the traditional iconography of the Baptism of Christ, marking the start of his ministry on earth.

In a similar way, the scene shows here marks the start of Venus's ministry of love, whether in a simple sense, or the expanded meaning of Renaissance Neoplatonism.

[30] More recently, questions have arisen about Neoplatonism as the dominant intellectual system of late 15th-century Florence,[31] and scholars have indicated that there might be other ways to interpret Botticelli's mythological paintings.

The iconography of The Birth of Venus is similar to a description of a relief of the event in Poliziano's poem the Stanze per la giostra, commemorating a Medici joust in 1475, which may also have influenced Botticelli, although there are many differences.

[35] Older writers, following Horne, posited that "his patron Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco asked him to paint a subject illustrating the lines",[36] and that remains a possibility, though one difficult to maintain so confidently today.

Another poem by Politian speaks of Zephyr causing flowers to bloom, and spreading their scent over the land, which probably explains the roses he blows along with him in the painting.

[37] Having a large standing female nude as the central focus was unprecedented in post-classical Western painting, and certainly drew on the classical sculptures which were coming to light in this period, especially in Rome, where Botticelli had spent 1481–82 working on the walls of the Sistine Chapel.

According to Pliny, Alexander the Great offered his mistress, Campaspe, as the model for the nude Venus and later, realizing that Apelles had fallen in love with the girl, gave her to the artist in a gesture of extreme magnanimity.

"[45] While Botticelli might well have been celebrated as a revivified Apelles, his Birth of Venus also testified to the special nature of Florence's chief citizen, Lorenzo de' Medici.

Tradition associates the image of Venus in Botticelli's painting with the famous beauty Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, of whom popular legend claims both Lorenzo and his younger brother, Giuliano, were great admirers.

Thus, in Botticelli's interpretation, Pankaspe (the ancient living prototype of Simonetta), the mistress of Alexander the Great (the Laurentian predecessor), becomes the lovely model for the lost Venus executed by the famous Greek painter Apelles (reborn through the recreative talents of Botticelli), which ended up in Rome, installed by Emperor Augustus in the temple dedicated to Florence's supposed founder Julius Caesar.

In the case of Botticelli's Birth of Venus, the suggested references to Lorenzo, supported by other internal indicators such as the stand of laurel bushes at the right, would have been just the sort of thing erudite Florentine humanists would have appreciated.

Accordingly, by overt implication, Lorenzo becomes the new Alexander the Great with an implied link to both Augustus, the first Roman emperor, and even to Florence's legendary founder, Caesar himself.

Ultimately, these readings of the Birth of Venus flatter not only the Medici and Botticelli but all of Florence, home to the worthy successors to some of the greatest figures of antiquity, both in governance and in the arts.

Once landed, the goddess of love will don the earthly garb of mortal sin, an act that will lead to the New Eve – the Madonna whose purity is represented by the nude Venus.

Once draped in earthly garments she becomes a personification of the Christian Church which offers a spiritual transport back to the pure love of eternal salvation.

This life-sized work depicts a similar figure and pose, partially clad in a light blouse, and contrasted against a plain dark background.

The coin, made of Nordic Gold, features a small effigy of Venus’ face and neck, encircled within twelve five-point stars, alongside an Italian Republic Monogram and its mint year.