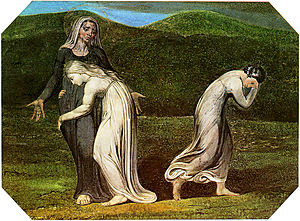

Book of Ruth

Written in Hebrew during the Persian period (c. 550-330 BCE),[2][3] the book is generally considered by scholars to be a work of historical fiction.

[6] The book is held in esteem by Jewish converts, as is evidenced by the considerable presence of Boaz in rabbinic literature.

Elimelech dies, and the sons marry two Moabite women: Mahlon weds Ruth and Chilion Orpah.

Early that morning, Boaz goes to the city gate to meet with the other male relative before the town elders.

They transfer the property, redeeming it, and ratify the redemption by the nearer kinsman taking off his shoe and handing it over to Boaz.

The women of the city celebrate Naomi's joy in finding a redeemer to preserve her family name.

[9] It is traditionally ascribed to the prophet Samuel (11th century BCE), but Ruth's identity as a non-Israelite and the stress on the need for an inclusive attitude towards foreigners suggests an origin in the fifth century BCE, when intermarriage had become controversial (as seen in Ezra 9:1 and Nehemiah 13:1).

[19] A large letter נ, a majuscula, occurs in the first word of Ruth 3:13 - לִינִי (lî-nî; "tarry, stay, lodge, pass the night") - which the smaller Masora ascribes to the Oriental or Babylonian textualists.

When Boaz wakes up, surprised to see a woman at his feet, Ruth explains that she wants him to redeem (marry) her.

[24][25][26][Note 1] Since there is no heir to inherit Elimelech's land, custom required a close relative (usually the dead man's brother) to marry the widow of the deceased in order to continue his family line (Deuteronomy 25:5–10).

[27] A complication arises in the story when it is revealed that another man is a closer relative to Elimelech than Boaz and therefore has first claim on Ruth.

[27] The book can be read as a political parable relating to issues around the time of Ezra and Nehemiah (the 5th century BCE):[8] unlike the story of Ezra–Nehemiah, where marriages between Jewish men and non-Jewish women were broken up, Ruth teaches that foreigners who convert to Judaism can become good Jews, foreign wives can become exemplary followers of Jewish law, and there is no reason to exclude them or their offspring from the community.

[28] Some believe the names of the participants suggest a fictional nature of the story: the husband and father was Elimelech, meaning "My God is King", and his wife was Naomi, "Pleasing", but after the deaths of her sons Mahlon, "Sickness", and Chilion, "Wasting", she asked to be called Mara, "Bitter".

[8] The reference to Moab raises questions, since in the rest of the biblical literature it is associated with hostility to Israel, sexual perversity, and idolatry, and Deuteronomy 23:3–6 excluded an Ammonite or a Moabite from "the congregation of the LORD; even to their tenth generation".

Feminists, for example, have recast the story as one of the dignity of labour and female self-sufficiency,[citation needed] and as a model for lesbian relations,[30] while others have seen in it a celebration of the relationship between strong and resourceful women.