The Botanic Garden

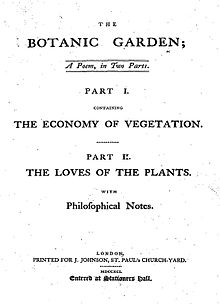

The Botanic Garden (1791) is a set of two poems, The Economy of Vegetation and The Loves of the Plants, by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin.

By embracing Linnaeus's sexualized language, which anthropomorphizes plants, Darwin intended to make botany interesting and relevant to the readers of his time.

One of the most prominent books about botany was William Withering's Botanical Arrangement of all the Vegetables Naturally Growing in Great Britain (1776), which used Linnaeus's system for classifying plants.

Therefore, as scholar Janet Browne writes, “to be a Linnaean taxonomist was to believe in the sex life of flowers.”[4] In his poem, Darwin not only embraced Linnaeus's classification scheme but also his metaphors.

[9] Concerned about his scientific reputation and curious to see if there would be an audience for his more demanding poem The Economy of Vegetation, he published The Loves of the Plants anonymously in 1789 (see 1789 in poetry).

Seward wrote that "the immense price which the bookseller gave for this work, was doubtless owing to considerations which inspired his trust in its popularity.

[12] Because amateur botany was popular in Britain during the second half of the eighteenth century, The Botanic Garden, despite its initial high cost, was a bestseller.

Despite the huge demand in 1799 and into the early 1800s, and cheaper pirated American and Irish imports, there was room in the market for another edition in Britain 1824 with a reprinting in 1825.

The poem is not a narrative; instead, reminiscent of the picaresque tradition, it consists of discrete descriptions of eighty-three separate species which are accompanied by extensive explanatory footnotes.

They also stimulate the readers' imaginations to assist them in learning the material and allow Darwin to argue that the plants he is discussing are animate, living things—just like humans.

Darwin's use of personification suggests that plants are more akin to humans than the reader might at first assume; his emphasis on the continuities between mankind and plantkind contributes to the evolutionary theme that runs throughout the poem.

Darwin writes that his poem will reverse Ovid who “did, by art poetic, transmute Men, Women, and even Gods and Goddesses, into trees and Flowers; I have undertaken, by similar art, to restore some of them to their original animality”[17] "When heaven's high vault condensing clouds deform, Fair Amaryllis flies the incumbent storm, Seeks with unsteady step the shelter'd vale, And turns her blushing beauties from the gale.

[23] The images also present a largely positive view of the relationship between the sexes; there is no rape or sexual violence of any kind, elements central to much of Ovid and Linnaeus.

[24] Despite its traditional gender associations, some scholars have argued that the poem provides “both a language and models for critiquing sexual mores and social institutions” and encourages women to engage in scientific pursuits.

[26] The poem at some points goes further, into what would now be called science fiction, forecasting that the British Empire will have giant steam-powered airships ("The flying-chariot through the fields of air.

Fair crews triumphant, leaning from above") and far-ranging submarines ("Britain's sons shall guide | Huge sea-balloons beneath the tossing tide; The diving castles, roof'd with spheric glass, Ribb'd with strong oak, and barr'd with bolts of brass, Buoy'd with pure air shall endless tracks pursue").

[29] As such examples demonstrate, The Economy of Vegetation is part of an Enlightenment paradigm of progress while The Loves of the Plants, with its focus on an integrated natural world, is more of an early Romantic work.

[30] Darwin also connected scientific progress to political progress; “for Darwin the spread of revolution meant that reason and equity vanquished political tyranny and religious superstition.”[31] Criticizing slavery, he writes: When Avarice, shrouded in Religion's robe, Sail'd to the West, and slaughter'd half the globe: While Superstition, stalking by his side, Mock'd the loud groan, and lap'd the bloody tide; For sacred truths announced her frenzied dreams, And turn'd to night the sun's meridian beams.— Hear, Oh Britannia!

potent Queen of isles, On whom fair Art, and meek Religion smiles, Now Afric's coasts thy craftier sons invade, And Theft and Murder take the garb of Trade!

—The Slave, in chains, on supplicating knee, Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee; With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress'd, 'Are we not Brethren?'

Until the publication of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads in 1798, Darwin was considered one of England's preeminent poets.

Anti-Jacobins, who were opposed to the French revolution, denounced the sexual freedom gaining ground in France and linked it to the scientific projects of men like Darwin.

"When heaven's high vault condensing clouds deform,

Fair Amaryllis flies the incumbent storm,

Seeks with unsteady step the shelter'd vale,

And turns her blushing beauties from the gale.

Six

rival youths, with soft concern impress'd,

Calm all her fears, and charm her cares to rest." (I.151-156)