Chinese Indonesians

Although the 1997 Asian financial crisis severely disrupted their business activities, reform of government policy and legislation removed most if not all political and social restrictions on Chinese Indonesians.

[9][10] These flourished during the period of Chinese nationalism in the final years of China's Qing dynasty and through the Second Sino-Japanese War; however, differences in the objective of nationalist sentiments brought about a split in the population.

[18] A recently created harbor was selected as the new headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) in 1609 by Jan Pieterszoon Coen.

[29] Some became revenue farmers, middlemen within the corporate structure of the VOC, tasked with collecting export–import duties and managing the harvest of natural resources;[30] although this was highly profitable, it earned the enmity of the pribumi population.

In its effort to build Chinese-speaking schools the association argued that the teaching of the English and Chinese languages should be prioritized over Dutch, to provide themselves with the means of taking, in the words of Phoa Keng Hek, "a two or three-day voyage (Java–Singapore) into a wider world where they can move freely" and overcome restrictions of their activities.

When the Dutch returned, following the end of World War II, the chaos caused by advancing forces and retreating revolutionaries also saw radical Muslim groups attack ethnic Chinese communities.

Other examples include Kwee Thiam Hiong member of Jong Sumatranen Bond [id], Abubakar Tjan Kok Tjiang and Thung Tjing Ek (Jakub Thung) exploits in Kaimana[74] and Serui respectively,[75] BPRT (Barisan Pemberontak Rakjat Tionghoa) which was founded in Surakarta on 4 January 1946, LTI (Lasjkar Tionghoa Indonesia) in Pemalang, and in Kudus Chinese descents became members of Muria Territorial Command called Matjan Poetih troops, a platoon size force under Mayor Kusmanto.

An integrationist movement, led by the Chinese-Indonesian organisation Baperki (Badan Permusjawaratan Kewarganegaraan Indonesia), began to gather interest in 1963, including that of President Sukarno.

As many as 500,000 people, the majority of them Javanese Abangan Muslims and Balinese Indonesians but including a minority of several thousand ethnic Chinese, were killed in the anti-communist purge[b] which followed the failed coup d'état, suspected as being communist-led, on 30 September 1965.

To prevent the ideological battles that occurred during Sukarno's presidency from resurfacing, Suharto's Pancasila democracy sought a depoliticized system in which discussions of forming a cohesive ethnic Chinese identity were no longer allowed.

"[90] The semi-governmental Institute for the Promotion of National Unity (Lembaga Pembina Kesatuan Bangsa, LPKB) was formed to advise the government on facilitating assimilation of Chinese Indonesians.

[91][92] During the 1970s and 1980s, Suharto and his government brought in Chinese Indonesian businesses to participate in the economic development programs of the New Order while keeping them highly vulnerable to strengthen the central authority and restrict political freedoms.

In a 1989 interview conducted by scholar Adam Schwarz for his book A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia's Search for Stability, an interviewee stated that, "to most Indonesians, the word 'Chinese' is synonymous with corruption".

[105] In the late 1990s and early 2000s during the fall of Suharto there was mass ethnic violence with Catholic Dayaks and Malays in west Borneo killing the state sponsored Madurese settlers.

[117] On 9 May 2017, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was sentenced to two years in prison after being found guilty of committing a criminal act of blasphemy, a move that was widely criticized by many as an attack on free speech.

[118] Chinese immigrants to the Indonesian archipelago almost entirely originated from various ethnic groups especially the Tanka people of what are now the Fujian and Guangdong provinces in southern China, areas known for their regional diversity.

Although they initially populated the mining centers of western Borneo and Bangka Island, Hakkas became attracted to the rapid growth of Batavia and West Java in the late 19th century.

Notable traditionally as skilled artisans, the Cantonese benefited from close contact with Europeans in Guangdong and Hong Kong by learning about machinery and industrial success.

This error was only corrected in 2008 when Aris Ananta, Evi Nuridya Arifin, and Bakhtiar from the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore published a report that accounted for all Chinese Indonesian populations using raw data from BPS.

The significance and pervasiveness of the social line between the two sectors varies from one part of Indonesia to another.Scholars who study Chinese Indonesians often distinguish members of the group according to their racial and sociocultural background: the totok and the peranakan.

[149] Kinship structure in the totok community follows the patrilineal, patrilocal, and patriarchal traditions of Chinese society, a practice which has lost emphasis in peranakan familial relationships.

[81] To identify the varying sectors of Chinese Indonesian society, Tan contends they must be differentiated according to nationality into those who are citizens of the host country and those who are resident aliens, then further broken down according to their cultural orientation and social identification.

[159] Aimee Dawis, citing prominent scholar Leo Suryadinata, believes the shift is "necessary to debunk the stereotype that they are an exclusive group" and also "promotes a sense of nationalism" among them.

The Teochew people are the majority within Chinese community in West Kalimantan province, especially in central to southern areas such as Kendawangan, Ketapang and Pontianak, as well as in the Riau Islands, which include Batam and Karimun.

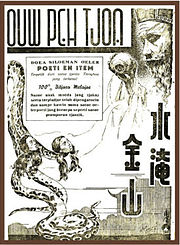

The growth of peranakan literature in the second half of the 19th century gave rise to such a variant, popularized through silat (martial arts) stories translated from Chinese or written in Malay and Indonesian.

The language was simply low, bazaar Malay, the common tongue of Java's streets and markets, especially of its cities, spoken by all ethnic groups in the urban and multi-ethnic environment.

[189] Because of these factors, the ethnic Chinese played a "significant role" in the development of the modern Indonesian language as the largest group during the colonial period to communicate in a variety of Malay dialects.

The rise of China's political and economic standing at the turn of the 21st century became an impetus for their attempt to attract younger readers who seek to rediscover their cultural roots.

[206] Local officials remained largely unaware that the civil registration law legally allowed citizens to leave the religion section on their identity cards blank.

On the other hand, young Chinese Indonesian women are typically addressed as cece or cici (shortened as ce or ci), stemming from jiějiě (姐姐, elder sister).