Torque

When being referred to as moment of force, it is commonly denoted by M. Just as a linear force is a push or a pull applied to a body, a torque can be thought of as a twist applied to an object with respect to a chosen point; for example, driving a screw uses torque to force it into an object, which is applied by the screwdriver rotating around its axis to the drives on the head.

The term torque (from Latin torquēre, 'to twist') is said to have been suggested by James Thomson and appeared in print in April, 1884.

[2][3][4] Usage is attested the same year by Silvanus P. Thompson in the first edition of Dynamo-Electric Machinery.

The single notion of a twist applied to turn a shaft is better than the more complex notion of applying a linear force (or a pair of forces) with a certain leverage.Today, torque is referred to using different vocabulary depending on geographical location and field of study.

[6] This terminology can be traced back to at least 1811 in Siméon Denis Poisson's Traité de mécanique.

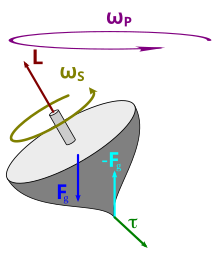

The resulting torque vector direction is determined by the right-hand rule.

Therefore any force directed parallel to the particle's position vector does not produce a torque.

This equation is the rotational analogue of Newton's second law for point particles, and is valid for any type of trajectory.

This result can easily be proven by splitting the vectors into components and applying the product rule.

Therefore, torque on a particle is equal to the first derivative of its angular momentum with respect to time.

There is not a universally accepted lexicon to indicate the successive derivatives of rotatum, even if sometimes various proposals have been made.

Mathematically, for rotation about a fixed axis through the center of mass, the work W can be expressed as

where τ is torque, and θ1 and θ2 represent (respectively) the initial and final angular positions of the body.

[13] It follows from the work–energy principle that W also represents the change in the rotational kinetic energy Er of the body, given by

Algebraically, the equation may be rearranged to compute torque for a given angular speed and power output.

The power injected by the torque depends only on the instantaneous angular speed – not on whether the angular speed increases, decreases, or remains constant while the torque is being applied (this is equivalent to the linear case where the power injected by a force depends only on the instantaneous speed – not on the resulting acceleration, if any).

The principle of moments, also known as Varignon's theorem (not to be confused with the geometrical theorem of the same name) states that the resultant torques due to several forces applied to about a point is equal to the sum of the contributing torques:

From this it follows that the torques resulting from N number of forces acting around a pivot on an object are balanced when

[17][18] Practitioners depend on context and the hyphen in the abbreviation to know that these refer to torque and not to energy or moment of mass (as the symbolism ft-lb would properly imply).

In the following formulas, P is power, τ is torque, and ν (Greek letter nu) is rotational speed.

Some people (e.g., American automotive engineers) use horsepower (mechanical) for power, foot-pounds (lbf⋅ft) for torque and rpm for rotational speed.

The use of other units (e.g., BTU per hour for power) would require a different custom conversion factor.

The problem with this definition is that it does not give the direction of the torque but only the magnitude, and hence it is difficult to use in three-dimensional cases.

For example, the torque on a current-carrying loop in a uniform magnetic field is the same regardless of the point of reference.

Internal-combustion engines produce useful torque only over a limited range of rotational speeds (typically from around 1,000–6,000 rpm for a small car).

Steam engines and electric motors tend to produce maximum torque close to zero rpm, with the torque diminishing as rotational speed rises (due to increasing friction and other constraints).

Reciprocating steam-engines and electric motors can start heavy loads from zero rpm without a clutch.

A cyclist, the person who rides the bicycle, provides the input power by turning pedals, thereby cranking the front sprocket (commonly referred to as chainring).

The input power provided by the cyclist is equal to the product of angular speed (i.e. the number of pedal revolutions per minute times 2π) and the torque at the spindle of the bicycle's crankset.

By using a larger rear gear, or by switching to a lower gear in multi-speed bicycles, angular speed of the road wheels is decreased while the torque is increased, product of which (i.e. power) does not change.