Grid plan

By 2600 BC, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, major cities of the Indus Valley civilization, were built with blocks divided by a grid of straight streets, running north–south and east–west.

[2] The cities and monasteries of Sirkap, Taxila and Thimi (in the Indus and Kathmandu Valleys), dating from the 1st millennium BC to the 11th century AD, also had grid-based designs.

[3] A workers' village (2570–2500 BC) at Giza, Egypt, housed a rotating labor force and was laid out in blocks of long galleries separated by streets in a formal grid.

Hammurabi king of the Babylonian Empire in the 18th century BC, ordered the rebuilding of Babylon: constructing and restoring temples, city walls, public buildings, and irrigation canals.

And for its layout the city should have the Royal Court situated in the south, the Marketplace in the north, the Imperial Ancestral Temple in the east and the Altar to the Gods of Land and Grain in the west."

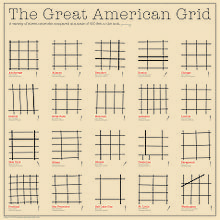

The Greek grid had its streets aligned roughly in relation to the cardinal points[5] and generally looked to take advantage of visual cues based on the hilly landscape typical of Greece and Asia Minor.

According to Stanislawski (1946), the Romans did use grids until the time of the late Republic or early Empire, when they introduced centuriation, a system which they spread around the Mediterranean and into northern Europe later on.

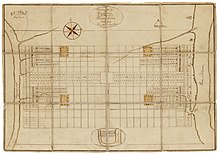

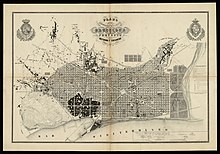

It was subsequently applied in the new cities established during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, after the founding of San Cristóbal de La Laguna (Canary Islands) in 1496.

The baroque capital city of Malta, Valletta, dating back to the 16th century, was built following a rigid grid plan of uniformly designed houses, dotted with palaces, churches and squares.

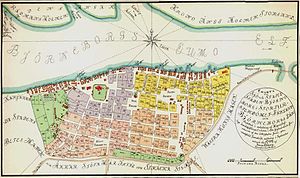

Being aware of the modern European construction experience which he examined in the years of his Grand Embassy to Europe, the Czar ordered Domenico Trezzini to elaborate the first general plan of the city.

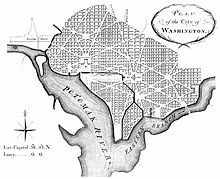

For example, when the legislature of the Republic of Texas decided in 1839 to move the capital to a new site along the Colorado River, the functioning of the government required the rapid population of the town, which was named Austin.

The Eixample grid introduced innovative design elements which were exceptional at the time and even unique among subsequent grid plans: These innovations he based on functional grounds: the block size, to enable the creation of a quiet interior open space (60 m by 60 m) and allow ample sunlight and ventilation to its perimeter buildings; the rectilinear geometry, the wide streets and boulevards to sustain high mobility and the truncated corners to facilitate turning of carts and coaches and particularly vehicles on fixed rails.

However, during the 1920s, the rapid adoption of the automobile caused a panic among urban planners, who, based on observation, claimed that speeding cars would eventually kill tens of thousands of small children per year.

In each case, the community unit at hand—the clan or extended family in the Muslim world, the economically homogeneous subdivision in modern suburbia—isolates itself from the larger urban scene by using dead ends and culs-de-sac.

Patterns that incorporate discontinuous street types such as crescents and culs-de-sac have not, in general, regarded pedestrian movement as a priority and, consequently, have produced blocks that are usually in the 1,000 feet (300 m) range and often exceed it.

Priene's plan, for example, is set on a hill side and most of its north–south streets are stepped, a feature that would have made them inaccessible to carts, chariots and loaded animals.

The same inflexibility of the grid leads to disregarding environmentally sensitive areas such as small streams and creeks or mature woodlots in preference for the application of the immutable geometry.

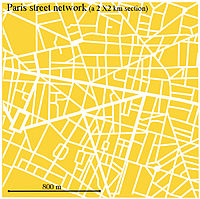

The grid plan with its frequent intersections may displace a portion of the local car trips with walking or biking due to the directness of route that it offers to pedestrians.

Since the grid plan is non-hierarchical and intersections are frequent, all streets can be subject to this potential reduction of average speeds, leading to a high production of pollutants.

The amount of traffic on a street depends on variables such as the population density of the neighbourhood, car ownership and its proximity to commercial, institutional or recreational edifices.

Similarly, a 1972 ground-breaking study by Oscar Newman on a Defensible Space Theory described ways to improve the social environment and security of neighbourhoods and streets.

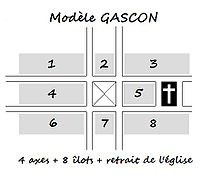

In a practical application of his theory at Five Oaks, the neighbourhood's grid pattern was modified to prevent through traffic and create identifiable smaller enclaves while maintaining complete pedestrian freedom of movement.

A recent study[42] did extensive spatial analysis and correlated several building, site plan and social factors with crime frequencies and identified subtle nuances to the contrasting positions.

A recent study in California[43] examined the amount of child play that occurred on the streets of neighbourhoods with different characteristics; grid pattern and culs-de-sac.

Similar studies in Europe[44] and most recently in Australia[45] found that children's outdoor play is significantly reduced on through roads where traffic is, or perceived by parents to be, a risk.

[46][47][48] Traditional street functions such as kids' play, strolling and socializing are incompatible with traffic flow, which the open, uniform grid geometry encourages.

For these reasons, cities such as Berkeley, California, and Vancouver, British Columbia, among many others, transformed existing residential streets part of a grid plan into permeable, linked culs-de-sac.

This transformation retains the permeability and connectivity of the grid for the active modes of transport but filters and restricts car traffic on the cul-de-sac street to residents only.

Perceived safety, though perhaps an inaccurate reflection of the number of injuries or fatalities, influences parents' decision to allow their children to play, walk or bike on the street.

Recent studies have found higher traffic fatality rates in outlying suburban areas than in central cities and inner suburbs with smaller blocks and more-connected street patterns.

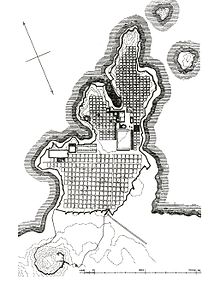

1.- Decumano; 2.- Cardo; 3.- Foro de Caesaraugusta ; 4.- Puerto fluvial ; 5.- Termas públicas ; 6.- Teatro ; 7.- Muralla