Translating Beowulf

The difficulty of translating Beowulf from its compact, metrical, alliterative form in a single surviving but damaged Old English manuscript into any modern language is considerable,[1] matched by the large number of attempts to make the poem approachable,[2] and the scholarly attention given to the problem.

mynte, se manscaða | manna cynnes, sumne besyrwan | in sele þam hean· Then under veils of mist came Grendel from the moor; he bare God's anger, the criminal meant to entrap some one of the race of men in the high hall.

[14] Here, Beowulf sets sail for Heorot in the poet David Wright's popular and frequently reprinted Penguin Classics prose version,[15] and in Seamus Heaney's prize-winning[16] verse rendering, with word-counts to indicate relative compactness: Fyrst forð gewat; | flota wæs on yðum, bat under beorge.

| Beornas gearwe on stefn stigon, — | strēamas wundon, sund wið sande; | secgas bæron on bearm nacan | beorhte frætwe, guðsearo geatolic; | guman ut scufon, weras on wilsīð | wudu bundenne.

The soldiers, in full harness, came aboard by the prow and stowed a cargo of polished armour and magnificent war-equipment amidships, while the sea churned and surf beat against the beach.

Men climbed eagerly up the gangplank, sand churned in surf, warriors loaded a cargo of weapons, shining war-gear in the vessel's hold, then heaved out, away with a will in their wood-wreathed ship.

[26] Burton Raffel writes in his essay "On Translating Beowulf" that the poet-translator "needs to master the original in order to leave it", meaning that the text must be thoroughly understood, and then boldly departed from.

[27] Magennis describes the version as highly accessible and readable, using alliteration lightly, and creating a "vivid and exciting narrative concerned with heroic exploits ... in a way that [the modern reader] can understand and appreciate.

[4] Here, the Danish watchman challenges Beowulf and his men as they arrive at Heorot: ... ... | þa ðær wlonc hæleð ōretmecgas | æfter æþelum frægn: 'Hwanon ferigeað ge | fætte scyldas, grǣge syrcan, | ond grimhelmas, heresceafta heap ?

There then a proud chief Of those lads of the battle speer’d after their line: Whence ferry ye then the shields golden-faced, The grey sarks therewith, and the helms all bevisor’d, And a heap of the war-shafts?

The poet and Beowulf translator Edwin Morgan stated that he was seeking to create a rendering in modern English that worked as poetry for his own age, while accurately reflecting the original.

Magennis describes the rendering of the passage as "sweeping steadily onwards", but "complicated by intricate grammatical development and abrupt oppositions, dense imagery and varied rhythmical effects and ... an insistently mannered diction", reflecting the original:[34] ... ... | Nō his līfgedāl sarlic þuhte | secga ænegum þara þe tīrlēases | trode sceawode, hu he werigmod | on weg þanon, niða ofercumen, | on nicera mere fǣge ond geflymed | feorhlastas bær.

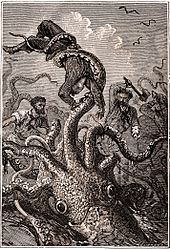

Ðær wæs on blode | brim weallende, atol yða geswing | eal gemenged, haton heolfre, | heorodrēore weol; deaðfæge deof; | siððan dreama lēas in fenfreoðo | feorh alegde, hæþene sawle; | þær him hel onfeng.

... Ungrievous seemed His break with life to all those men Who gazed at the tracks of the conquered creature And saw how he had left on his way from that place – Heart-fatigued, defeated by the blows of battle, Death-destined, harried off to the tarn of krakens - His life-blood-spoor.

There the becrimsoned Waters were seething, the dreadful wave-sweep All stirred turbid, gore-hot, the deep Death-daubed, asurge with the blood of war, Since he delightless laid down his life And his heathen soul in the fen-fastness, Where hell engulfed him.

Tolkien noted that whatever a translator's preferences might be, the ancients such as the Beowulf poet had chosen to write of times already long gone by, using language that was intentionally archaic and sounding poetic to their audiences.

[36] His versions of Beowulf's voyage to Heorot in prose and verse, the latter in strictest Anglo-Saxon alliteration and metre[c] (with Tolkien's markup of metrical stresses), are: Gewat þa ofer wǣgholm | winde gefysed flota famiheals | fugle gelicost, oð þæt ymb antid | oþres dogores wundenstefna | gewaden hæfde, þæt ða liðende | land gesawon, brimclifu blican, | beorgas steape, side sænæssas; | þa wæs sund liden, eoletes æt ende.

| þanon up hraðe Wedera lēode | on wang stigon, sæwudu sældon,— | syrcan hrysedon, guðgewædo; She wènt then over wáve-tòps, | wínd pursúed her, fléet, fóam-thròated | like a flýing bírd; and her cúrving prów | on its cóurse wáded, till in dúe séason | on the dáy áfter those séafàrers | sáw befóre them shóre-cliffs shímmering | and shéer móuntains, wíde cápes by the wáves: | to wáter's énd the shíp had jóurneyed.

Over the waves of the deep she went sped by the wind, sailing with foam at throat most like unto a bird, until in due hour upon the second day her curving beak had made such way that those sailors saw the land, the cliffs beside the ocean gleaming, and sheer headlands and capes thrust far to sea.

[41][42] The novelist Maria Dahvana Headley's 2020 translation is relatively free, domesticating and modernising, though able to play with Anglo-Saxon-style kennings, such as rendering aglæca-wif as "warrior-woman", meaning Grendel's mother.

Her feminism is visible in her rendering of the lament of the Geatish woman at the end of the poem:[43] ... | Higum unrōte modceare mændon, | mondryhtnes cwealm; swylce giōmorgyd | Geatisc meowle æfter Biowulfe | bundenheorde song sorgcearig, | sæde geneahhe, þæt hio hyre hearmdagas | hearde ondrede, wælfylla worn, | wīgendes egesan, hynðo ond hæftnyd.

A Geat woman with braided hair keened a dirge in Beowulf's memory, repeating again and again that she feared bad times were on the way, with bloodshed, terror, captivity, and shame.

[44][45] Heaney, a Catholic poet from Northern Ireland (often called "Ulster"), could domesticate Beowulf to the old rural dialect of his childhood family only at the risk of being accused of cultural appropriation.

He opted to re-create the cadences of Old English, seeking in María José Gómez-Calderón's view to "reproduce the dignified, elevated tone" and "remarkabl[y]" keeping the number of syllables down to fit the metre convincingly, as shown by the sombre conclusion of the poem:[47] Swa begnornodon | Geata leode hlafordes hryre, | heorðgeneatas.

Knútsson gives as an instance of this the use of "bægsli" for "shoulder" rather than "öxl", cognate with Old English "eaxl" in line 1539; this recalls the fourteenth-century Gull-Þóris saga, which some scholars believe is linked to Beowulf – it tells of a hero and his men who venture into a cave of dragons who are guarding a treasure.

Greip þá í bægsli - glímdi ósmeykur - Gautaleiðtogi Grendils móður; Gripped then by the bægsli– wrestled undismayed the Geatish leader – Grendel's mother The author of a popular[50] and widely used[50] 1973 translation, Michael J. Alexander, writes that since the story was familiar to its Anglo-Saxon audience, the telling was all-important.

[5] Alexander gives as example lines 405–407, telling that Beowulf speaks to Hrothgar – but before he opens his mouth, there are three half-lines describing and admiring his shining mail-shirt in different ways:[5] heard under helme, | þæt he on heorðe gestod.

Liuzza notes that Beowulf itself describes the technique of a court poet in assembling materials:[6] ... | Hwīlum cyninges þegn, guma gilphlæden, | gidda gemyndig, se ðe ealfela | ealdgesegena worn gemunde | —word oþer fand soðe gebunden— | secg eft ongan sið Bēowulfes | snyttrum styrian, ond on sped wrecan | spel gerade, wordum wrixlan; | ... At times the king's thane, full of grand stories, mindful of songs, who remembered much, a great many of the old tales, found other words truly bound together; he began again to recite with skill the adventure of Beowulf, adeptly tell an apt tale, and weave his words.

Liuzza comments that wrixlan (weaving) and gebindan (binding) evocatively suggest the construction of Old English verse, tying together half-lines with alliteration and syllable stresses, just as rhyme and metre do in a Shakespearean sonnet.