Trypanosoma brucei

T. brucei is transmitted between mammal hosts by an insect vector belonging to different species of tsetse fly (Glossina).

[14] Winterbottom described a key feature of the disease as swollen posterior cervical lymph nodes and slaves who developed such swellings were ruled unfit for trade.

He initially noted them as a kind of filaria (tiny roundworms), but by the end of the year established that the parasites were "haematozoa" (protozoan) and were the cause of nagana.

[17] The scientific name was created by British zoologists Henry George Plimmer and John Rose Bradford in 1899 as Trypanosoma brucii due to printer's error.

[3][18] The genus Trypanosoma was already introduced by Hungarian physician David Gruby in his description of T. sanguinis, a species he discovered in frogs in 1843.

[26] The Commission comprised George Carmichael Low from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine as the leader, his colleague Aldo Castellani and Cuthbert Christy, a medical officer on duty in Bombay, India.

[33] In February 1902, the British War Office, following a request from the Royal Society, appointed David Bruce to lead the second Sleeping Sickness Commission.

[34] With David Nunes Nabarro (from the University College Hospital), Bruce and his wife joined Castellani and Christy on 16 March.

[26] Castellani left Africa in April and published his report as "On the discovery of a species of Trypanosoma in the cerebrospinal fluid of cases of sleeping sickness" in The Lancet.

[9] Around the same time, Germany sent an expeditionary team led by Robert Koch to investigate the epidemic in Togo and East Africa.

Bateman and Frederick Percival Mackie, established the basic developmental cycle through which the trypanosome in tsetse fly must pass.

Muriel Robertson,[40][41] in experiments carried out between 1911 and 1912, established how ingested trypanosomes finally reach the salivary glands of the fly.

[42]Another human trypanosome (now called T. brucei rhodesiense) was discovered by British parasitologists John William Watson Stephens and Harold Benjamin Fantham.

[9] In 1910, Stephens noted in his experimental infection in rats that the trypanosome, obtained from an individual from Northern Rhodesia (later Zambia), was not the same as T. gambiense.

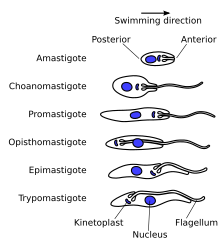

In addition, there is an unusual organelle called the kinetoplast, which is a complex of thousands of interlinked circles of mitochondrial DNA known as mini- and maxicircles.

It is made up of a typical flagellar axoneme, which lies parallel to the paraflagellar rod,[63] a lattice structure of proteins unique to the kinetoplastids, euglenoids and dinoflagellates.

The flagellum is bound to the cytoskeleton of the main cell body by four specialised microtubules, which run parallel and in the same direction to the flagellar tubulin.

[70] T. brucei completes its life cycle between tsetse fly (of the genus Glossina) and mammalian hosts, including humans, cattle, horses, and wild animals.

In stressful environments, T. brucei produces exosomes containing the spliced leader RNA and uses the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) system to secrete them as extracellular vesicles.

[48] The long slender forms are able to penetrate the blood vessel endothelium and invade extravascular tissues, including the central nervous system (CNS)[68] and placenta in pregnant women.

The serpins including GmmSRPN3, GmmSRPN5, GmmSRPN9, and especially GmmSRPN10 are then hijacked by the parasite to aid its own midgut infection, using them to inactivate bloodmeal trypanolytic factors which would otherwise make the fly host inhospitable.

[76] The second cycle, which usually occurs in late-stage infection, involves unequal mitosis that produces two different daughter cells from the mother epimastigote.

The basal body, unlike the centrosome of most eukaryotic cells, does not play a role in the organisation of the spindle and instead is involved in division of the kinetoplast.

[72] In addition to the major form of transmission via the tsetse fly, T. brucei may be transferred between mammals via bodily fluid exchange, such as by blood transfusion or sexual contact, although this is thought to be rare.

Melarsopol is the only drug effective against the two types of parasite in both infection stages,[98] but is highly toxic, such that 5% of treated individuals die of brain damage (reactive encephalopathy).

[102][103] German physician Paul Ehrlich and his Japanese associate Kiyoshi Shiga developed the first specific trypanocidal drug in 1904 from a dye, trypan red, which they named Trypanroth.

For this reason, these proteins are highly immunogenic and an immune response raised against a specific VSG coat will rapidly kill trypanosomes expressing this variant.

[151] Hpr is 91% identical to haptoglobin (Hp), an abundant acute phase serum protein, which possesses a high affinity for hemoglobin (Hb).

This induces a conformational change in the ApoL1 membrane addressing domain which in turn causes a salt bridge linked hinge to open.

[158] Other factors involved in resistance appear to be a change in the cysteine protease activity and TbHpHbR inactivation due to a leucine to serine substitution (L210S) at codon 210.