Ventricular fibrillation

The ventricular muscle twitches randomly rather than contracting in a coordinated fashion (from the apex of the heart to the outflow of the ventricles), and so the ventricles fail to pump blood around the body – because of this, it is classified as a cardiac arrest rhythm, and patients in V-fib should be treated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and prompt defibrillation.

Left untreated, ventricular fibrillation is rapidly fatal as the vital organs of the body, including the heart, are starved of oxygen.

Some clinicians may attempt to defibrillate fine V-fib in the hope that it can be reverted to a cardiac rhythm compatible with life, whereas others will deliver CPR and sometimes drugs as described in the advanced cardiac life support protocols in an attempt to increase its amplitude and the odds of successful defibrillation.

[citation needed] Ventricular fibrillation has been described as "chaotic asynchronous fractionated activity of the heart" (Moe et al. 1964).

A more complete definition is that ventricular fibrillation is a "turbulent, disorganized electrical activity of the heart in such a way that the recorded electrocardiographic deflections continuously change in shape, magnitude and direction".

In the Brugada syndrome, changes may be found in the resting ECG with evidence of right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST elevation in the chest leads V1–V3, with an underlying propensity to sudden cardiac death.

[11] Familial conditions that predispose individuals to developing ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death are often the result of gene mutations that affect cellular transmembrane ion channels.

The ionic basic automaticity is the net gain of an intracellular positive charge during diastole in the presence of a voltage-dependent channel activated by potentials negative to –50 to –60 mV.

The length of the refractory period and the time taken for the dipole to travel a certain distance—the propagation velocity—will determine whether such a circumstance will arise for re-entry to occur.

Factors that promote re-entry would include a slow-propagation velocity, a short refractory period with a sufficient size of ring of conduction tissue.

[citation needed] In clinical practice, therefore, factors that would lead to the right conditions to favour such re-entry mechanisms include increased heart size through hypertrophy or dilatation, drugs which alter the length of the refractory period and areas of cardiac disease.

The use of this is often dictated around the world by Advanced Cardiac Life Support or Advanced Life Support algorithms, which is taught to medical practitioners including doctors, nurses and paramedics and also advocates the use of drugs, predominantly epinephrine, after every second unsuccessful attempt at defibrillation, as well as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) between defibrillation attempts.

Though ALS/ACLS algorithms encourage the use of drugs, they state first and foremost that defibrillation should not be delayed for any other intervention and that adequate cardiopulmonary resuscitation be delivered with minimal interruption.

Some advanced life support algorithms advocate its use once and only in the case of witnessed and monitored V-fib arrests as the likelihood of it successfully cardioverting a patient are small and this diminishes quickly in the first minute of onset.

[citation needed] People who survive a "V-fib arrest" and who make a good recovery are often considered for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, which can quickly deliver this same life-saving defibrillation should another episode of ventricular fibrillation occur outside a hospital environment.

It exacts a significant mortality with approximately 70,000 to 90,000 sudden cardiac deaths each year in the United Kingdom, and survival rates are only 2%.

[citation needed] Lyman Brewer suggests that the first recorded account of ventricular fibrillation dates as far back as 1500 BC, and can be found in the Ebers papyrus of ancient Egypt.

Tests done on frozen remains found in the Himalayas seemed fairly conclusive that the first known case of ventricular fibrillation dates back to at least 2500 BC.

[25] John A. MacWilliam, a physiologist who had trained under Ludwig and who subsequently became Professor of Physiology at the University of Aberdeen, gave an accurate description of the arrhythmia in 1887.

His description is as follows: "The ventricular muscle is thrown into a state of irregular arrhythmic contraction, whilst there is a great fall in the arterial blood pressure, the ventricles become dilated with blood as the rapid quivering movement of their walls is insufficient to expel their contents; the muscular action partakes of the nature of a rapid incoordinate twitching of the muscular tissue … The cardiac pump is thrown out of gear, and the last of its vital energy is dissipated in the violent and the prolonged turmoil of fruitless activity in the ventricular walls."

[28] The re-entry mechanism was also advocated by DeBoer, who showed that ventricular fibrillation could be induced in late systole with a single shock to a frog heart.

[30] This was called the "vulnerable period" by Wiggers and Wegria in 1940, who brought to attention the concept of the danger of premature ventricular beats occurring on a T wave.

He described ventricular fibrillation as "an incoordinate type of contraction which, despite a high metabolic rate of the myocardium, produces no useful beats.

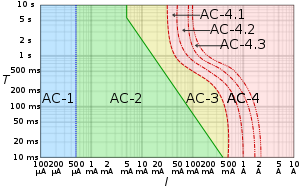

AC-1: imperceptible

AC-2: perceptible but no muscle reaction

AC-3: muscle contraction with reversible effects

AC-4: possible irreversible effects

AC-4.1: up to 5% probability of ventricular fibrillation

AC-4.2: 5–50% probability of fibrillation

AC-4.3: over 50% probability of fibrillation