Verism

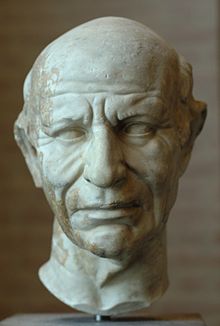

Rather, they too can be highly exaggerated or idealised, but within a different visual idiom, one which favours wrinkles, furrows, and signs of age as indicators of gravity and authority.

[2]: 54 The artist carved the woman with sunken cheeks and pouches under her eyes to illustrate her age, much like male veristic portraiture of the time.

[2]: 54 Verism, while the height of fashion during the Late Republican era, quickly fell into obscurity when Augustus and the rest of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (44 BC-68 AD) came to power.

Scholars believe that Vespasian used the shift from the Classical style to that of veristic portraiture to send a visual propagandistic message distinguishing him from the previous emperor.

Vespasian's portraits showed him as an older, serious, and unpretentious man who was in every respect the anti-Nero: a career military officer concerned not for his own pleasure but for the welfare of the Roman people, the security of the Empire, and the solvency of the treasury.

[3] From a central Italian provenance in ancient times tribes from this area used Terracotta and Bronze to make a somewhat realistic portrayal of the human head.

[3] Scholars note that none of the realistic looking specimens can be shown to be earlier than the arrival of the new wave of Greek influence, rather than vice versa.

H. Drerup argues that death masks molded straight from the face were used early in Rome, and exerted a ‘direct influence’ on Republican portraits.

Suggested stylistic dates often fluctuate by two or three centuries leaving scholars with no solid evidence for when the style of harshly realistic Egyptian portraiture begun.

[1]: 31 Historians also note Romans did not have extensive military or commercial contact with Egypt before 30 BC, which was after the Late Republic when verism was being used on portraiture.

[1]: 34 This interest leaked similar portrayals seen in the more realistic Hellenistic royal portraits of the Pontic and Bactrian kings of the first half of the 2nd century BC, such as the slight turn of their heads and upward glance of the eyes, into Roman veristic busts.

[1]: 34 As Rome conquered Greece the empire saw an influx of talented Greek artists who were commissioned by the Romans to create their portraits that portrayed both the Hellenistic look and Republic values.

[1]: 35 As a result, the Greek artist would maintain the Hellenistic ‘pathos formula’ – turn of the head and neck, eyes looking upward – but the Greek sculptor, rather than adapt the Roman's features to a Hellenistic ruler ideal, had concentrated on bringing out an air of caricature to the face leading to what scholars call veristic portraiture.

[1]: 37 As a result, some art historians, like R. R. R. Smith, believe verism originated from the negative Greek attitudes, if not somewhat unconscious attitudes, the artists felt towards these particular foreign clients, which was allowed to work itself into the Roman portraits because the artists had been freed from the usual obligation to flatter and idealized the sitter and instead allowed to sculpt without artifice.