Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive transmutation of species in an accessible narrative which tied together numerous scientific theories of the age.

Vestiges was initially well received by polite Victorian society and became an international bestseller, but its unorthodox themes contradicted the natural theology fashionable at the time and were reviled by clergymen – and subsequently by scientists who readily found fault with its amateurish deficiencies.

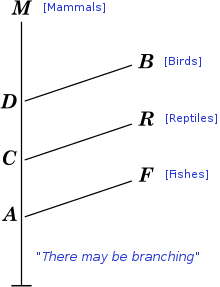

It then appeals to geology to demonstrate a progression in the fossil record from simple to more complex organisms, finally culminating in man, with the Caucasian European the pinnacle of this process, just above the other races and the rest of the animal kingdom.

(p. 154)He furthermore suggests that this interpretation may be based upon corrupt theology: Thus, the scriptural objection quickly vanishes, and the prevalent ideas about the organic creation appear only as a mistaken inference from the text, formed at a time when man's ignorance prevented him from drawing therefrom a just conclusion.

(p. 156)And praises God for his foresight in generating such wondrous variety from so elegant a method, while chastening those who would oversimplify His accomplishment: To a reasonable mind the Divine attributes must appear, not diminished or reduced in some way, by supposing a creation by law, but infinitely exalted.

"No vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end..." James Hutton (1785) The Theory of the Earth.The book argued for an evolutionary view of life in the same spirit as the late Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

Now it is possible that wants and the exercise of faculties have entered in some manner into the production of the phenomena which we have been considering; but certainly not in the way suggested by Lamarck, whose whole notion is obviously so inadequate to account for the rise of the organic kingdoms, that we only can place it with pity among the follies of the wise.

(p. 231)In an (anonymous) autobiographical preface written in the third person that only appeared in the 10th edition, Chambers remarked that "He had heard of the hypothesis of Lamarck; but it seemed to him to proceed upon a vicious circle, and he dismissed it as wholly inadequate to account for the existence of animated species.

Every afternoon for a period early in 1845, Prince Albert read it aloud to Queen Victoria as a suitable popular science book explaining the latest ideas from the continent.

Prophetic of infidel times, and indicating the unsoundness of our general education, "The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation," has started into public favour with a fair chance of poisoning the fountains of science, and sapping the foundations of religion.

He sought to sanitise the radical tradition by presenting progressive evolution as an unfolding of divinely planned laws of creation as development up to and including the appearance of human species.

Several carried substantial reviews, one of the first appearing in mid November 1844 in the weekly reform newspaper the Examiner:[10] In this small and unpretending volume, we have found so many great results of knowledge and reflection, that we cannot too earnestly recommend it to the attention of thoughtful men.

An attempt which presupposed learning, extensive and various; but not the large and liberal wisdom, the profound philosophical suggestion, the lofty spirit of beneficence, and the exquisite grace of manner which make up the charm of this extraordinary book.

Churchill had already been alarmed by The Lancet's report of numerous mistakes, and had been surprised to find that, unlike the medical specialists he usually dealt with, the author of Vestiges lacked first hand knowledge of the subject or the ability to correct proofs.

In defence of public morals and Evangelical Tory dominance in the city, the Reverend Abraham Hume, an Anglican priest and lecturer, delivered a detailed attack on Vestiges at the Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society on 13 January 1845, demonstrating that the book conflicted with standard specialist scientific texts on nebulae, fossils and embryos, and accusing it of manipulative novelistic techniques occupying "the debatable ground between science and fiction".

[17] Anglican clergymen were usually quick to publish pamphlets on any theological controversy, but tended to excuse themselves from responding to Vestiges as they lacked expertise: men of science were expected to lead the counterattack.

William Whewell refused all requests for a review to avoid dignifying the "bold, speculative and false" work, but was the first to give a response, publishing Indications of a Creator in mid February 1845 as a slim and elegant volume of "theological extracts" from his writings.

Sir John Cam Hobhouse wrote his thoughts down in his diary: "In spite of the allusions to the creative will of God the cosmogony is atheistic—at least the introduction of an author of all things seems very like a formality for the sake of saving appearances—it is not a necessary part of the scheme".

Lord Morpeth thought it had "much that is able, startling, striking" and progressive development did not conflict with Genesis more than then current geology, but did "not care much for the notion that we are engendered by monkeys" and objected strongly to the idea that the Earth was "a member of a democracy" of similar planets.

[19] Vestiges was published in New York, and in response the April 1845 issue of the North American Review published a long review,[20] the start of which was scathing about its reliance on speculative scientific theories: "The writer has taken up almost every questionable fact and startling hypothesis, that have been promulgated by proficients and pretenders in science during the present century...The nebular hypothesis...spontaneous generation...the Macleay system, dogs playing dominoes, negroes born of white parents, materialism, phrenology, - he adopts them all, and makes them play an important part in his own magnificent theory, to the exclusion, to a great degree, of the well-accredited facts and established doctrines of science.

He turned down several invitations to review Vestiges, pleading lack of time, but in March read it closely and on 6 April discussed with other leading clergymen the "rank materialism" of the book "against which work he & all other scientific men are indignant".

Sedgwick expressed concern for "our glorious maidens and matrons .... listening to the seductions of this author; who comes before them with a bright, polished, and many-coloured surface, and the serpent coils of a false philosophy, and asks them again to stretch out their hands and pluck forbidden fruit", who tells them "that their Bible is a fable when it teaches them that they were made in the image of God—that they are the children of apes and breeders of monsters—that he has annulled all distinction between physical and moral", which in Sedgwick's view would lead to "a rank, unbending and degrading materialism" lacking the proper reading of nature as analogy to draw moral lessons from physical truths.

Aristocrats found its "lengthy inefficiency" heavy going, and John Gibson Lockhart of the Tory Quarterly Review suspected that "The savants are all sore at the vestige man because they are likely to be in the same boat as him."

The extreme liberal press also thought "a mere anonymous bookmaker might well be sacrificed to evidence the orthodoxy of a Cambridge divine", in the hope of "immunity to their own speculations, by a cheap display of eloquent zeal against all who dare to go beyond their measure.

[30] The North British Review reflected evangelical Presbyterian willingness to consider science in relation to "Reason and not to Faith" and to view natural law as directly guided by God, but warned that "If it has been revealed to man that the Almighty made him out of the dust of the earth, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, it is in vain to tell a Christian that man was originally a speck of albumen, and passed through the stages of monads and monkeys, before he attained his present intellectual pre-eminence.

"[32][33] Chambers planned one more "edition for the higher classes and for libraries", extensively revised to deal with errors and incorporate the latest science, such as the detail of the Orion Nebula revealed by Lord Rosse's giant telescope.

[41] In his introduction to On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, Darwin assumed that his readers were aware of Vestiges, and wrote identifying what he felt was one of its gravest deficiencies with regards to its theory of biological evolution: The author of the Vestiges of Creation would, I presume, say that, after a certain unknown number of generations, some bird had given birth to a woodpecker, and some plant to the mistletoe, and that these had been produced perfect as we now see them; but this assumption seems to me to be no explanation, for it leaves the case of the coadaptations of organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life, untouched and unexplained.

"It seems to the author," Chambers wrote, "that Mr. Darwin has only been enabled by his infinitely superior knowledge to point out a principle in what may be called practical animal life, which appears capable of bringing about the modifications theoretically assumed in the earlier work.

[44] In a historical sketch, newly added to the 3rd edition, Darwin softened his language a bit: The author apparently believes that organisation progresses by sudden leaps, but that the effects produced by the conditions of life are gradual.

But I cannot see how the two supposed "impulses" account in a scientific sense for the numerous and beautiful co-adaptations which we see throughout nature; I cannot see that we thus gain any insight how, for instance, a woodpecker has become adapted to its peculiar habits of life.