Virginia v. John Brown

Within a fortnight from the time when Brown had struck what he believed to be a righteous blow against what he felt to be the greatest sin of the age he was a condemned felon, with only thirty days between his life and the hangman's noose.

[9][10][11][12][13] The stories in the New York Daily Tribune were published unsigned, as the reporter, Edward Howard House, was in Charles Town in disguise, under a false name, with credentials from a Boston pro-slavery paper.

[20] The illustrations were so widely distributed that Yale Literary Magazine made fun of them, publishing the drawings of "our own artist on the spot" of "Governor Wise's shoes", "John Brown's watch", and the like.

[25] The Secretary of War, after a lengthy meeting with President Buchanan, telegraphed Lee that the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, Robert Ould, was being sent to take charge of the prisoners and bring them to justice.

[28][29] As he put it, after claiming that he remained at Harper's Ferry to prevent the suspects from being lynched,[30] he "had made up his mind fully, and after determining that the prisoners should be tried in Virginia, he would not have obeyed an order to the contrary from the President of the United States.

Because of Senator Mason's resolution setting up a "select committee" to investigate the events at Harpers Ferry, there was no need of a federal venue in order to summon witnesses from other states.

People began to think he was not such a terrible monster after all, and some expressions of pity for his condition were even heard; but when, upon finding that his witnesses were absent, Brown rose and denounced his counsel, declaring he had no confidence in them, the indignation of the citizens scarcely knew bounds.

[62] The final plea by the defense team for mercy concerned the circumstances surrounding the death of two of John Brown's men, who were apparently fired upon and killed by the Virginia militia while under a flag of truce.

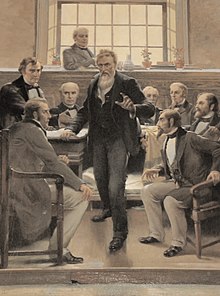

[23]: 340 In his speech, Brown said that his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and also that the entire criminal trial had been more fair than he expected.

The delay meant that the issue grew further; Brown's raid, trial, visitors, correspondence, upcoming execution, and Wise's role in making it happen were reported on constantly in newspapers, both local and national.

[74] Delegations called on both Hoyt and Sennott to warn them of violence if they did not leave; the mayor said he had no force with which to resist the lynch mob expected to assemble the next day, Sunday.

"[74] Sennott refused, but Hoyt left the same day, together with Mr. Jewett, an artist from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, suspected to have also been the undercover New-York Tribune reporter.

Many things that Governor Wise did augmented rather than reduced tensions: by insisting he be tried in Virginia, and by turning Charles Town into an armed camp, full of state militia units.

His only possible involvement was from his power to pardon, and he had received "petitions, prayers, threats from almost every Free State in the Union," warning that Brown's execution would turn him into a martyr.

[23]: 295 Now that he had been convicted and sentenced, there were no more restrictions on visitors, and Brown, relishing the publicity his anti-slavery views received, talked to reporters or anyone else that wanted to see him, although abolitionists, like Rebecca Buffum Spring, could only visit him with great difficulty.

"[96] On November 28, Brown wrote the following to an Ohio friend, Daniel R. Tilden: I have enjoyed remarkable cheerfulness and composure of mind since my confinement; and it is a great comfort to feel assured that I am permitted to die (for a cause)[,] not merely to pay the debt of nature (as all must).

[50]: 45 Ralph Waldo Emerson's prediction, in a lecture on November 8, that Brown, if executed, "would make the gallows glorious, like the cross,"[98] "was responded to by the immense audience in the most enthusiastic manner.

[100] The New York Independent said the following of him during this month: The brave old man who lies in prison at Charlestown, Virginia, awaiting the day of his execution, is teaching this nation lessons of heroism, faith and duty, which will awaken its sluggish moral sense, and the almost forgotten memories of the heroes of the Revolution.

[119][120] He gave a similar, even stronger form of the same statement to jailer Hiram O'Bannon: I am now convinced that the great iniquity which hangs over this country cannot be purged without immense bloodshed.

A prospective visitor from northwestern Pennsylvania, where Brown had lived for 11 years, was told in Philadelphia not to proceed, as martial law had in fact been declared in "the country around Charlestown".

[33] As further protection, "a field-piece loaded with grape and canister had been planted directly in front of and aimed at the scaffold, so as to blow poor Brown's body to smithereens in the event of attempted rescue.

Wise...gives as the reason for this exclusion of all save the military, that in the event of an attempted rescue an order to fire upon the prisoner will be given, and that those within the line, especially those sufficiently near the gallows to hear what Brown may say, would inevitably share his fate.

[130]When the four collaborators arrested and convicted with Brown were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".

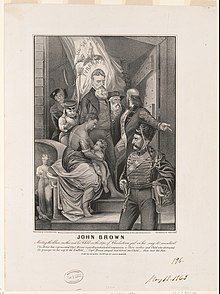

"[41]: 174 [139]: 446 [140] On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon,[141] Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue.

The orations, speeches, sympathy, approvals, the proposal to toll bells, close stores, &c., without any public manifestation to the contrary, has created a state of feeling at the South that is not to be described.

[157] In Syracuse, New York, City Hall was "densely packed" with citizens, who listened to over three hours of speeches and contributed "a large amount of money" to aid his family.

[174] In Boston, on December 8, former Massachusetts Governors Edward Everett and Levi Lincoln Jr. addressed an anti-John Brown rally, that filled Faneuil Hall to capacity.

Virginia is now the tyrant, as explained on the day of Brown's sentencing by abolitionist Wendell Phillips, to whom, along with Thoreau and the young Emerson, Redpath's volume is dedicated: It is a mistake to call him an insurrectionist.

It is not what John Brown has done or failed to do, but the fearful possibilities that his crazy emeute [commotion, disturbance] has opened to view, which have inspired the South with a terror of coming evil.

Foolhardy as was Brown's exploit, regarded merely as a military invasion for the rescue of the oppressed, unjustifiable as it was upon the principles of Christian ethics, yet this singular devotion of an old man to the cause of human freedom, his heroic contempt of his own life, blending with a sacred regard for the lives and property of others, except where these should stand in the way of the deliverance of the oppressed[,] are gradually pervading the public mind with a tone of admiration even for a misguided philanthropy, and startling the South with the idea that a philanthropy which will peril life for its object, is more to be feared than despised.