Virivore

Virivore (equivalently virovore) comes from the English prefix viro- meaning virus, derived from the Latin word for poison[citation needed], and the suffix -vore from the Latin word vorare, meaning to eat, or to devour;[1] therefore, a virivore is an organism that consumes viruses.

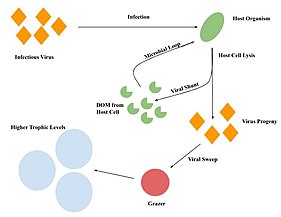

Viruses are considered a top predator in marine environments, as they can lyse microbes and release nutrients (i.e. the viral shunt).

Viruses also play an important role in the structuring of microbial trophic relationships and regulation of carbon flow.

[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] In 2022, DeLong et al. showed that over the course of two days the ciliates Halteria and Paramecium reduced chlorovirus plaque-forming units by up to two orders of magnitude, supporting the idea that nutrients were transferred from the viruses to consumers.

It's known that small protists, such as Halteria and Paramecium, are consumed by zooplankton indicating the movement of viral-derived energy and matter up through the aquatic food web.

This contradicts the idea that the viral shunt limits the movement of energy up food webs by cutting off the grazer-microbe interaction.

Studies show that digested viral particles release amino acids that the grazer can then utilize during their own polypeptide synthesis.

[14] Trophic interactions between grazers, bacteria, and viruses are important in regulating nutrient and organic matter cycling.

[13] Additionally, the impact of the viral sweep could be more significant if grazers preying on bacteria infected with viruses are also considered.

[16] Filter feeders usually actively capture single food particles on cili, hairs, mucus, or other structures.

[14] Over the 90 days, viral abundances steadily decreased when co-incubated with T. coloniensis, showing that grazing is an effective mechanism for feeding on viruses.

[2] There is huge diversity amongst marine viruses, including size, shape, morphology, and surface charge that may influence the selection, and therefore ingestion rates.

[18][19] Copepods are a key link in marine food webs as they connect primary and secondary production with higher trophic levels.

[19] Infected E. huxleyi exhibit increased cell size compared to non-infected, making them an ideal prey for O.

[19] Preferential grazing on infected cells would make the carbon available to higher trophic levels by sequestering it in particulate form.

[14][20] The observation that grazers could potentially release viruses back into the environment after ingestion could have significant ecological impacts.

[20] These virion containing pellets were then co-incubated with a fresh culture of E. huxleyi, and rapid viral-mediated lysis of the host cells was observed.

[20] The absence of virion particles in the fecal pellets produced from sole EhV incubation supports the idea that grazers exhibit selective grazing for viruses.

[20] Additionally, fecal pellets can sink from the mixed layer into deeper parts of the ocean, where they can be assimilated multiple times.

Non-host organisms such as anemones, polychaeta larvae, sea squirts, crabs, cockles, oysters, and sponges are all capable of significantly reducing the viral abundance.

[23] These mechanisms cause a reduction in the virus-host contact rates which could significantly impact local microbial population dynamics.