Voyage of the Brooklyn Saints

Despite pleas for law enforcement, government officials rarely intervened to protect Latter-day Saint settlements, citing a difficult political situation or openly siding with anti-Mormon mobs.

"[38] In the years preceding the Mormon exodus, Joseph Smith and other church leaders made repeated attempts to engage local, state, and federal authorities in protecting them from mob attacks, in obtaining restitution for damaged or stolen property, and in supporting their Constitutional right to freedom of worship.

Brigham Young announced on September 16, 1845, that the Latter-day Saints would abandon their headquarters city of Nauvoo, Illinois, when overland travel became possible in the spring as vegetation grew on the prairie to feed livestock.

At that time, the Great Basin was part of Alta California, a sparsely populated region, nominally under the jurisdiction of Mexico, but primarily occupied by indigenous people (Ute, Dine' (Navajo), Paiute, Goshute, and Shoshone).

The ship Brooklyn was loaded with hundreds of agricultural tools, mechanical supplies, and large items like grist mill stones and a printing press to lay the groundwork for the new colony in the West.

The arrival of large numbers of American settlers by land and by sea could serve U.S. president, James K. Polk's strategic objectives as the United States vied with Great Britain and France for control of the Pacific coast.

In part to address that issue, President Polk authorized the enlistment of 500 men from migrating Mormon wagon trains on the plains into General Stephen Watts Kearny's Army of the West.

Samuel Brannan wrote to Brigham Young about the proposition, claiming to have "learned that the secretary of war and other members of the cabinet were laying plans and were determined to prevent the Mormons from moving west, alleging that it was against the law for an armed body of men to go from the United States to any other government.

"[62] Based on Brannan's letters, Young's diary for January 29, 1846, stated "that the Government intended to intercept our movements – by placing strong forces in the way to take from us all fire arms – on the grounds that we were going to another Nation.

[69] Captain Lansford Hastings, leader of the 1842 emigration to Oregon and California, wrote a pro-California guide book from which Samuel Brannan printed pages in the New-York Messenger, 1 November 1845 issue.

To initiate his strategy to take Alta California, U.S. President Polk sent secret orders in November 1845 to the Pacific Squadron and to Captain John C. Frémont via Archibald Gillespie, who carried the messages covertly across Mexico.

Brooklyn's black hull contrasted with a wide, white stripe above the water line, emphasizing faux gun ports, set off by a horn of plenty figurehead beneath the bowsprit.

[95] At a farewell social gathering shortly before sailing, a prominent New York attorney and literary society president named Joshua M. Van Cott presented the group with 179 volumes of the Harper Family Library.

With the help of other family members a few days later, Ann and the children managed to escape on foot across snowy New Jersey back roads, making their way across the state to reunite with Isaac just before Brooklyn sailed.

Days consisted of reveille at 6 am, cleaning of staterooms, inspections, sick call, meals served in two seatings, school for the children, religious services on Sundays, with people assigned on a rotating basis to watch over belongings and food supplies, and much free time.

[112] "Some who were more resolute struggled to the deck to behold the sublime grandeur of the scene – to hear the dismal howl of the winds, and to see the ship with helm lashed, pitching, rolling, dipping in the trough of the sea and then tossed on the highest billow.

The participants would act jointly to make preparations for members of the overland emigration; would pay the final transportation debt; and would give the proceeds of their labor for the next three years to a common fund, from which all would draw their living.

[132][127] While the Brooklyn was delivering its 800 pounds of freight, they secretly picked up at least three brass cannon mounted as light artillery, powder, shot, and a large supply of ammunition that had been shipped there by A. G. Benson the previous fall.

[134] A potential international incident was averted when, "during the ship Brooklyn layover in Honolulu, several natives came aboard and when they saw the 9-month old Kittleman twin girls, Sally and Hannah, they were delighted and immediately wanted permission to take them ashore and show them to their Queen.

Those on board the Brooklyn did not know that on July 1, 1846, Captain John Charles Frémont and his company, including Kit Carson and twenty Delaware natives,[137] already spiked the three ancient brass and seven iron cannon at the presidioO.

Nine months after landing, Samuel Brannan turned over leadership of church business to Glover[150] while the expedition leader ventured across the Sierras in search of Brigham Young's pioneer company coming west.

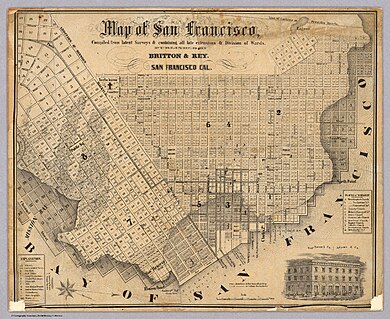

More than a year's work had gone into fencing farms against wild cattle, building roads and bridges, constructing homes, and establishing businesses in the San Francisco Bay area—all with the expectation that at least 12,000 fellow Mormons would soon arrive as customers, land purchasers, users of services, and community members.

In early March, Battalion veterans Sidney Willis, Wilford Hudson, and Levi Fifield located an even richer find twelve miles down river at Mormon Island.

Long before the rest of "the world rushed in," Brooklyn pioneers and other Mormon settlers already in California carried out placer mining at Salmon Falls, Murderer's Bar, south along the Cosumnes River, and at other rich sites.

Initial reports of the ready availability of extensive mineral wealth were not believed, even by California's Military Governor Richard Barnes Mason, until he and his lieutenant, William Tecumseh Sherman, visited the mining districts in person.

They re-built San Francisco together after city-wide fires, attended church together, married one another, and migrated to the Great Salt Lake Valley together over a road built by the Mormon Battalion veterans.

Unsure if the recruitment offer was intended as a test of allegiance to the United States or as a ploy to make the scattered Latter-day Saints more vulnerable to attack along the trail, many men were reluctant to leave their families in exposed wagons on the plains.

In 1857 when Brigham Young asked Latter-day Saints to come stand with the church in Utah against the approach of Johnston's Army, Cheney led a small wagon train to Deseret over the Mormon Emigrant Trail.

[179] He was the last head of a Mormon congregation in the San Francisco Bay Area for many years until Brigham Young re-opened branches of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California.

Of his early efforts Horner wrote, "Flour mills not being sufficient in California at this time, we built one at Union City... at a cost of eighty-five thousand dollars, and ground our grain and that of others... We equipped and ran a stage line in connection with our steamer, as far up the valley as San Jose, twenty-five miles.